Hamlet: Into the Abyss

The foregoing discussion has emphsized a phylogenetic and unconscious etiology for the problem of history. But there is a related set of explanations to contend with–a set which focuses on the human need to escape the unconscious terror of finitude, impermenence, and mortality. This view was masterfully knit togetheer by Ernest Becker in his epochal The Denial of Death. This invisible and ubiquitous terror is almost always screened from human consciousness. Yet invisible though it may seem to be, it is the central driver for the cultural behaviors that continue to kneecap human progress.

Its overwhelming presence can is most easily detected in all of the arts–especially tragic drama, and with poetry.

As such, it begins precisely where the following stanza ends:

I dream of journeys repeatedly:

Of flying like a bat deep into a narrowing tunnel,

Of driving alone, without luggage, out a long peninsula,

The road lined with a snow-laden second growth,

A fine dry snow ticking the windshield,

Alternate snow and sleet, no on-coming traffic,

And no lights behind in the blurred side-mirror,

The road changing from glazed tarface to a rubble of stone,

Ending at last in a hopeless sand rut,

Where the car stalls,

Churning in a snowdrift

Until the headlights darken. (Roethke)

The anticipation of one’s own death is a by-product of the increased intelligence that fueled–and was is shaped by–hominid evolution. This is the knowledge that not only separates humanity from the innocent and perishable beasts, but which also separates its bearers from the fantasied heavens. Caught as they are within the imaginary gulf that separates earth and stars, humans struggle mightily to be safe, to achieve, to be loved–knowing all the while the power of time and death to destroy it all.

Come, let us sport us while we may…

For at my back I always hear

Time’s winged chariot drawing near.

(Andrew Marvell)

Because it is homo sapiens’ lot to live with one eye cast warily over its shoulder–the price that all hominids paid for moving out onto the wide open plain of forethought–it should be no wonder that our national and individual lives are filled with conflict.

This is the conflict that must arise when intelligent beings struggle to have and to enjoy a limited number of experiences and goods (maximize their fitness), all the while consciously aware of the appalling finitude of their own lives. This is the conflict that arises from the horror of the birth trauma, ego-differentiation, and the irreversible journey toward death.

The drivennes to acquire might serve to mitigate some of these losses, though the failure to acquire may itself become another peace-shattering loss.

We have seen earth’s frenzied images before: impatient single-horsed riders, squads of Conestoga wagons, all set against the dusty, prairie backdrop. Somewhere a gun goes off and the riders lurch forward, scrambling to occupy the claims that many of them had secretly laid out far in advance of the opening of the new territories.

Or move forward in time to witness the domestic privations of a distant and prolonged war. The doors unlock and swing wide. Women swarm into the department store, their purses acting as cudgels, their high heels spiking into enemy ankles and calves. Watch as these fierce maenads struggle in anguish to lay hold of a scarce pair of nylons. Two, like famished robins struggling for a worm, tug and tug at one precious stocking which sadly stretches to three times its length and then expires. Still more women surge in through the open doors, a tidal wave of human desire.

In many ways, life resembles a game show where the contestants are given forty five seconds to fill their shopping carts–where the very scarcity of time coupled with unbounded desire reduces many otherwise sane individuals to whirling dervishes. Up and down the aisles they sprint, sweeping whole shelf-fulls of goods into their groaning carts in an effort to fill them before the gigantic second hand makes its final sweep. The crowd shrieks in agony as a male contestant foolishly overlooks the expensive, valuable steaks and reaches for the boxed frozen chickens instead. The frenzy reaches a crescendo, the buzzer raucously sounds, but none of them ever “Beats the Clock.”

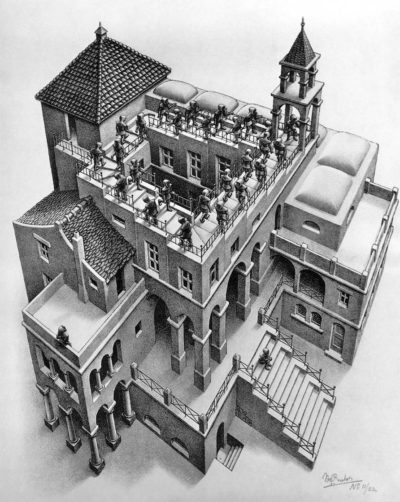

“Who,” Holbein asks in his Dance of Death, “is the man, however strong or great, that can cheat grim death of its final victory?”

His Nobleman (a latter day Laocoon) struggles here with a laughing death image, futilely attempting to cut himself loose from the bonds of necessity. How wonderfully the landscape and the objects of the print enhance the theme. An hourglass, resting behind him on what is to be his bier, has run its course. Great, grey clouds swirl over a blasted, raw cordillera.

Such an image, or one very like it, is doubtless the inspiration for this bumper sticker:

Whoever collects the most toys

Before he dies is the winner.

This is a pithy distillation of the bitter broth of life, but the vision from which it springs is not new:

“King: Now, Hamlet, where’s Polonius?

Ham: At supper.

King: At supper! Where?

Ham: Not where he eats, but where he is eaten. A certain convocation of politic worms are e’en at him. Your worm is your only emperor for diet. We fat all creatures else to fat ourselves, and we fat ourselves for maggots. Your fat king and your lean beggar is but variable service, two dishes, but to one table. That’s the end.

King: Alas, alas!

Ham: A man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king, and eat of the fish that hath fed of that worm.

King: What dost thou mean by this?

Ham: Nothing but to show you how a king may go a progress through the guts of a beggar.”

Shakespeare’s Hamlet is freighted with imagery not only of death and destruction as natural processes, but also as emblems of a divine antagonism between an absentee god and his rotting creation; an antagonism which Shakespeare uses to draw us beyond the neutrality of the impersonal laws of physics, leading us ever downward into a chaotic world where to live is to be corrupted, and where to love is to participate in a vile, purposeless drama awash in the stench of skulls and wormy clay. A universe whose “common theme is death of fathers.”

Of course, Hamlet’s father was poisoned, and so his death was neither natural nor timely. But behind these circumstances loom larger facts. One is that being mortal, all human beings are ultimately poisoned by life and its processes, and another is that no death is timely to one who can imagine a better, more durable, or a less painful world. In this sense Claudius becomes merely the agent for a larger chaos.

To look seriously and deeply into life, much as does our humanistic Hamlet when he regards the empty sockets of the court jester’s skull, is to come face to face with a terrible realization. It is to grow up, or as Freud might have said, “to become educated to reality.”

Holding the skull of Yorick, our hero asks:

Ham: Dost thou think Alexander looked o’ this fashion i’ th’ earth?

Hor: E’en so.

Ham: And smelt so?

Hor: E’en so, my lord.

Ham: To what base uses we may return, Horatio! Why may not in imagination trace the noble dust of Alexander, till he find it stopping a bung hole?

Hor: ‘Twere to consider too curiously, to consider so.

Ham: No, faith, not a jot; but to follow him thither with modesty enough, and likelihood to lead it; as thus: Alexander died, Alexander was buried, Alexander returneth into dust; the dust is earth; of earth we make loam; and why of that loam, whereto he was converted, might they not stop a beer barrel? Imperious Caesar, dead and turned to clay, Might stop a hole to keep the wind away.”

This is a variation on the theme that Claudius had suggested at the outset of the play:

“Tis sweet and commendable in your nature, Hamlet to give these mourning duties to your father; but you must know your father lost a father; that father lost, lost his; and the survivor bound, in filial obligation, for some term to do obsequious sorrow. But to persever in obstinate condolement is a course of impious stubbornness; ’tis unmanly grief; it shows a will most incorrect to heaven, a heart unfortified, a mind impatient, an understanding simple and unschool’d; for what we know must be, and is as common as any the most vulgar thing to sense, why should we in our peevish opposition take it to heart? Fie! ’tis a fault to heaven, a fault against the dead, a fault to nature, to reason most absurd; whose common theme is death of fathers, and who still hath cried, from the first corse till he that died to-day, This must be so.'”

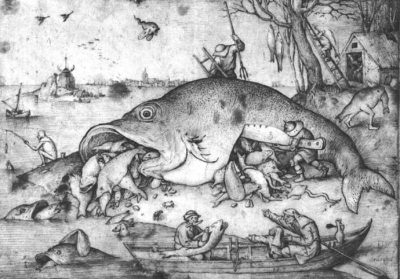

Claudius forces the pouting prince to confront a world not unlike that depicted by Brueghel in his Parable of the Fishes; a world where the gobbling propensities of the fish have spread to encompass both land and air. The cannon and other implements of war on the far horizon are merely the state’s ways of dining on its neighbors.

It is a world, the gustatory enthusiasm of which, Ernest Becker’ Escape From Evil describes in its own inimitable style:

“At its most elemental level the human organism,like crawling life, has a mouth, digestive tract, and anus; a skin to keep it intact, and appendages with which to acquire food. Existence, for all organismic life, is a constant struggle to feed– a struggle to incorporate whatever other organisms they can fit into their mouths and press down their gullets without choking. Seen in these stark terms, life on this planet is a gory spectacle, a science-fiction nightmare in which digestive tracts fitted with teeth at one end are tearing away at whatever flesh they can reach, and at the other end are piling up the fuming waste excrement as they move along in search of more flesh. I think this is why the epoch of the dinosaurs exerts such a strange fascination on us: it is an epic food orgy with king-size actors who convey unmistakably what organisms are dedicated to. Sensitive souls have reacted with shock to the elemental drama of life on this planet, and one of the reasons that Darwin so shocked his time–and still bothers ours–is that he showed this bone-crushing, blood-drinking drama in all its elementality and necessity: Life cannot go on without the mutual devouring of organisms. If at the end of each person’s life he were to be presented with the living spectacle of all that he had organismicaly incorporated in order to stay alive, he might well feel horrified by the living energy he had ingested. The horizon of a gourmet, or even the average person, would be taken up with hundreds of chickens, flocks of lambs and sheep, a small herd of steers, sties full of pigs, and rivers of fish. The din alone would be deafening. To paraphrase Elias Canetti, each organism raises its head over a field of corpses, smiles into the sun, and declares life good”.

How is one to withstand such knowledge; and how is one thereafter to continue cheerfully with life? This is a conscious dilemma, the solution to which threatens to outrace the simple imperatives of gene transmission. The towering fears of the imagination may at times override the fundamental behaviors insisted upon by the evolutionary dialectics of DNA.

Concluding that it might have been better had he not been born, our weary Hamlet contemplates suicide: to be or not to be. In such moments our hero bears the full weight of an unredemable existential awareness–a knowledge that has been described in many languages and in many forms.

Next: A Plague of Dreams: Death of a Salesman: Or: Back to Index