Death of A Salesman:

The Perils of Separation

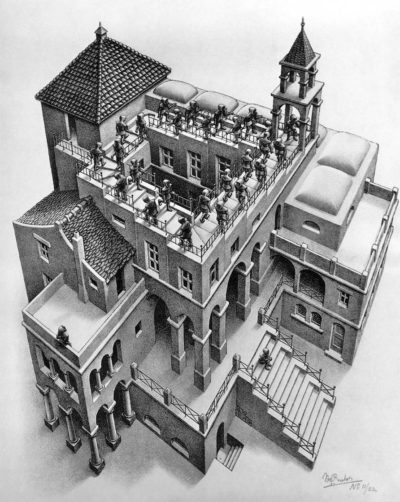

A fragile vessel bobs like a sodden cork beneath heavily threatening clouds. Some of its passengers are resigned, others near to expiring, and still others are intent on keeping watch, perhaps believing in the imminence (or immanence) of rescue. They have gathered at what they believe to be the front of the raft, near a makeshift mast. But they have no rudder to steer by. Great blasts of wind impel them in the opposite direction from that which they imagine their rescue might come. A dead man, his legs dowsing the surface of the shark filled sea, leads them on their way.

Is life a chaos without a center; a pointless journeying toward annihilation? Is no one is ever safe; does anyone ever arrive?

Journey within a journey, the ticket

mislaid or lost; the gate inaccessible

the boat always pulling away from the

rickety wooden dock; the children waving…

(Roethke)

Humankind’s first journey–the frantic stampede of single cells pushing forward into the immense darkness of inner space– ends with one’s birth, an unwilling entrance into the world of light. Separated from the comforting darkness, the child learns to seek in close embraces, and in the tightly wrapped swaddling clothes, the calm security of its first home.

But not even these can compensate for the trauma of birth separation. To be born is to journey, is to enter a world ruled by time and change. Not even one’s god-like parents can guarantee safety, destined as they themselves are to precede their offspring into a darkness they cannot avoid:

“Linda: Biff, a man is not a bird, to come and go with the springtime.

Biff: Your hair…(he touches her hair) Your hair got so gray.

Linda: Oh, it’s been gray since you were in high school. I just stopped dyeing it, that’s all.

Biff: Dye it again, will ya? I don’t want my pal looking old. (He smiles.)

Linda: You’re such a boy! You think you can go away for a year and…You’ve got to get it into your head now that one day you’ll knock on this door and there’ll be strange people here.” (Arthur Miller, Death of a Salesman)

Is it any wonder that the motif of the journey inhabits the core of the world’s literature and religions? The journey and its accumulating losses is the serpent that has been created to charm.

The Losses of the Monomyth derive from an overarching separateness: separation of the living from the non-living, of light from darkness, of consciousness from the undifferentiated, of up from down.

Most profoundly, each person confronts the most fundamental choice of all: whether to individuate or continue to accept the authority and values of one’s parents–the “gods” of each young person’s world.

This choice is uniquely human, and replicates in each generation both the primal drama and dilemma of Eden. “By evolving our own autonomy…we are killing our parents. We are usurping their power, their competence, their responsibility for us, and we are abnegating, rejecting them as libidinal objects. In short, we destroy them in regard to some of their qualities hitherto most vital to us” (Loewald 1979).

Surrogates are found in short order. Heaven is so familiar because humans themselves have made it. And though most of the blueprint has been hallucinated, the most essential features of its architecture derive from the ground of lived experience. The paradox of a loving god dooming all his creatures to die models the dynamic of the home: a child’s birth always sentences it to die.

The combined weight of the journey and its losses compels social and religious delusions of transcendent denial. “Part of every culture is thus `defense’ mechanism,” says LaBarre (1954). “All culture, all man’s creative life-ways, are in some basic part of them a fabricated protest against natural reality, a denial of the truth of the human condition, and an attempt to forget the pathetic creature that man is” (Becker, 1973).

Why pathetic? Because, in the words of Bertrand Russell, existence itself may be pointless:

“Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labors of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins…”

The psychoanalytical description of character as defense is commonplace in its literature: “In the prison of one’s character one can pretend and feel that he is somebody, that the world is manageable, that there is a reason for one’s life, a ready justification for one’s action” (Becker, 1973). Further, since “reality is terribly hard to bear….[the] prime function of the human institution and [our] cultural artifacts…is to put reality under a fantasy control” (Stein, 1987).

In Becker’s estimation:

“Man is a worm and food for worms…he is dual, up in the stars and yet housed in a heart-pumping, breath-gasping body that once belonged to a fish and still carries the gill-marks to prove it. His body is a material fleshy casing that is alien to him in many ways–the strangest and most repugnant way being that it aches and bleeds and will decay and die…he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order blindly and dumbly to rot forever.” (1973).

Most members of any society obey the commandment “to live automatically and uncritically.” In this way each can be assured of “at least a minimum share of the programmed cultural heroics–what we might call `prison heroism’: the smugness of the insiders who know” (ibid).

Much of the territory staked out by human cultures can be described as a transitional space filled with transitional objects (Deri, after Winnicott, 1978). In this sense, many cultural artifacts–and not only religious ones–are required to play a role somewhat analogous to that of Linus’ soiled blanket. To mitigate losses, some facsimile of the certainty, comfort or power hallucinated in the infantile darkness may be conjured to accompany the traveler who fares forward into an identity-cancelling void.

Thus the transitional object is itself invested with social and reified symbolic meaning: “the young child acts toward the transitional object as he or she would act toward the mother. The object is seen as protective and nurturant, and the child wants to be near it…The transitional realm will be populated, so to speak, with dead objects conjured into social life by inner perceptual biases and corresponding preoccupations” (Wenegrat 1990).

From this perspective, culture can in some ways be regarded as a vast elementary school playground; a psychic amusement park or children’s fantasy land wherein “each person grounds himself in some power that transcends him. Usually it is a combination of his parents, his social group, and the symbols of his society and nation. This is the unthinking web of support which allows him to believe in himself, as he functions on the automatic security of delegated powers” (Becker, 1973).

Infantilism, the avoidance of reality, the persistence of the omnipotence of wishes, the cultural fabrication of outsized transitional objects, the predisposition to surrender to authority figures or ideologies in whom one can trust and from whom one receives security– if this is indeed the product of our evolutionary heritage that is reified and enabled by cultural creation, then it seems that adults may never get the opportunity to grow up. The child ages; but the child remains dependent and, at bottom, a child.

The abreaction of the fixations and unacknowledged terrors of childhood is the core content of the very best of the tragedians:

“A melody is heard played upon a flute. It is small and fine telling of grass and trees. The curtain rises. Before us is the salesman’s house. We are aware of towering, angular shapes behind it surrounding it on all sides. Only the blue light of the sky falls upon the house and forestage; the surrounding area shows an angry glow of orange. As more light appears, we see a solid vault of apartment houses around the small, fragile seeming home. An air of the dream clings to the place, a dream rising out of reality.”

This is Arthur Miller’s play Death of a Salesman, and its central theme whorls around a terrible discovery: the universe regards wishing human individuals without obligation, and refuses to keep any of the promises they imagined it had made to them:

“Willy: Well, tell you the truth, Howard. I’ve come to the decision that I’d rather not travel any more.

Howard: Not travel! Well, what’ll you do?

Willy: Remember, Christmas time, when you had the party here? You said you’d try to think of some spot for me here in town.

Howard: With us?

Willy: Well, sure.

Howard: Oh, yeah, yeah. I remember. Well, I couldn’t think of anything for you, Willy.

Willy: I tell ya, Howard. The kids are all grown up, y’know. I don’t need much any more. If I could take home–well, sixty-five dollars a week, I could swing it.

Howard: Yeah, but Willy, see I–

Willy: I tell ya why, Howard. Speaking frankly and between the two of us, y’know– I’m just a little tired.

Howard: Oh, I could understand that, Willy. But you’re a road man, Willy, and we do a road business. We’ve only got a half-dozen salesmen on the floor here.

Willy: God knows, Howard, I never asked a favor of any man. But I was with the firm when your father used to carry you in here in his arms.

Howard: I know that, Willy, but–

Willy: Your father came to me the day you were born and asked me what I thought of the name of Howard, may he rest in peace.

Howard: I appreciate that, Willy, but there is just no spot here for you. If I had a spot I’d slam you right in, but I just don’t have a single solitary spot.”

Miller’s Death of a Salesman portrays humanity’s desperate struggle to amount to something in this world; it shows us the drive many individuals feel to leave some kind of monument, some testimonial that one has been here.

As Willy argues: “A man can’t go out the way he came in, Ben, a man has gotta add up to something.”

This goes a long way toward explaining Willy’s preoccupation with money. In this play, money is valued not only for the things it can buy, but for its ability to purchase power– a surrogate for immortality. And so the play transports the reader back to the dawn of civilization, and recapitulates several of the means that humans use to console themselves for reality.

It is no accident that the earliest money in civilization was both round and gold, for as such it symbolized the sun. Dispensed by the priests from their temples, the money icon has always had religious connotations, even down to the time of the Calvinists who saw prosperity as a sign of their god’s favor. The possession of the gold coin entitled one to participate in the source of power and life here on earth. Money insulated its owner from the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. Indeed, the more money one had, the more one was able to move like a god through this dying world.

The sun was the supreme symbol for renewal and resurrection –especially in Egyptian religion. Its daily journey through the heavens served as a macrocosm for the miniaturized journey of each human life. Dying a death each day at sunset, the great god Re sank into the darkness of the underworld. At last, the journey through the twelve hours of the night near completion, he would be rejuvenated with the help of Khepri, a scarab beetle who fastened himself to Re at the eleventh hour.

The promise of resurrection was writ in gigantic characters across the sky, and were readable to all. To some interpreters, the sun did not move across the sky in a boat but was instead rolled by a giant scarab, much as the real insect rolled balls of dung across the fields prior to burying them. So it is that faeces and and decomposition played significant roles in the immortality equation.

These mythic connections run rife in Miller’s play, and make it a virtual potpourri of the history of human hopefulness and delusion.

Bernard, the neighbor boy, is shit; but the sun forms a halo around Biff’s (Mithra’s) head during the Ebbetts field game. To put on a good performance before the scouts (judgmental gods) is to perhaps become another Red Grange, able to earn the then enormous sum of $25,000 per year. Reminiscing years later about the game, Linda and Willy describe Biff as a “young Hercules,” one who was “dressed in gold.” Of course, “a star like that, magnificent, can never really fade away.”

In Euripides’ play Alcestis, Hercules wrestled with death and won, and similar associations are invoked when Willy talks with his sons about their prospects in the business world. Convinced of their powers, he thanks god he’s “got a couple of Adonises here!” These latter day reincarnations of Adonis will doubtless gather more gold than all their competitors.

Still, Willy puzzles as to just how he and his sons can achieve what he imagines is rightfully theirs. As part of their training, Willy winks at their petty and not so petty thieving. After they steal “a couple of dozen six by tens, worth all kinds of money,” Willy tells Uncle Ben that he has a “couple of fearless characters there.” To Charley’s claim that “the jails are full of fearless characters,” Ben rejoinds: “And the stock exchange, friend!”

The stock exchange is the height of human achievement: a mortal facsimile of Olympus. And so we are reminded that Prometheus was both a hero and a thief, and further that the great god Zeus– certainly the chief broker on an outsized Wall Street– was himself a thief, having murdered his father Cronos to acquire his present position. Thievery is sanctified both by life and by the gods. After all, mortals must steal immortality for it has been denied them by the gods. The only thing that matters is that the hero gets the gold. If he does, when “he enters the store the waves (will) part right in front of him.”

But Miller’s heroes are not gods, and so are subject to the laws of change and decay. At the end, anemic Bernard gets the gold and the god-like power. The hero-athlete Biff becomes shit, and Willy finds himself babbling about seeds and death in a public toilet.

Sun, gold, haloes, high hopes: none of these delivers the family members from their mortal commonness, or from their excremental fate.

The impending collapse of Willy’s faith is prefigured by degeneration of the old neighborhood. Once a paradise in which to raise a family, Brooklyn has now become an oppressive slum.

Cornered in a labyrinth of his own stubborn delusions, Willy speaks to us in images of a monumental, psychic projection and cosmic claustrophobia:

“Willy: Why don’t you open a window in here,for God’s sake?

Linda: They’re all open, dear.

Willy: The way they boxed us in here. Bricks and windows, windows and bricks.

Linda: We should’ve bought the land next door.

Willy: The street is lined with cars. There’s not a breath of fresh air in the neighborhood. The grass don’t grow any more, you can’t raise a carrot in the back yard. They should have had a law against apartment houses. Remember those two beautiful elm trees out there? When Biff and I hung the swing between them?

Linda: Yeah, like being a million miles from the city.

Willy: They should’ve arrested the builder for cutting those down.”

And because he can’t control the change which is symbolized in the slippage of the present– the tape recorder that won’t shut off, the refrigerator that “consumes belts like a goddam maniac,” and the car’s steering wheel, Willy is compelled more and more to live in the past, an Eden which he has frozen in his imagination, an idyllic recollection which he has wrested from the grip of decay.

It was in that past that all the possibilities remained golden and bright; long before expectation was replaced by reality, long before the mortal family had begun to ring up its inevitable losses. It will be Willy’s inability to stop time, to stop the break up of life that is symbolized by the loss of that remembered brightness, that will urge him to wrest his narcissistic self-valuation from annihilation via suicide.

Only in death, as it will be for Lenny in Steinbeck’s Mice and Men, will the longed for anti-paradise appear to be attainable:

“Oh, Ben, how do we get back to all the great times? Used to be so full of light, and comradeship, the sleigh riding in winter, and the ruddiness on his cheeks. And always some kind of good news coming up, always something nice coming up ahead.”

But even that is a delusion. The insurance money he had intended for Biff never comes through.

Keats said that “all joys want eternity.” But that, alas, is just what mortals can’t have. It is Tantalizing to imagine possessing that which the law of life insists must be denied. Only a god could want what the gods have– but heroes are not gods. But then, neither are the gods–which makes a striving after their nonexistent perquisites all the more futile, self-flagellating.

The central tenet of this approach to life is to recognize that humans are not gods, and that they should turn away from god-striving delusions that diminish the value of the here and now. True heroism is finding the courage to settle for less, and to live simply before death comes. The battle is not with the Other, for as Epictetus once put it, one may not successfully control the world, but one may control one’s response to it.

Biff Loman is finally the hero if Miller’s play, not Willy. Biff sits all day in Bill Oliver’s* reception room–waiting for an interview with the god-like sporting goods mogul atop his high rise Mount Olympus. When Oliver leaves at day’s end, he brushes past our hero, claiming neither to know, nor to be interested in, anything he might have to say.

Crushed and left alone, Biff sees that the door to Oliver’s office stands open. In an unconscious panic attack, our young Prometheus steps in, steals a golden fountain pen from the desktop, and sprints breathlessly down eleven flights of stairs. He reaches the eleventh hour of Re’s journey to the underworld, and is about to be resuscitated by an earthbound realization, come from Khepri the dung roller who breathes new life into the moribund sun god of the Egyptian myth.

He emerges into the sunlight, bethinks himself, and is struck with a magnificent revelation.

The old values of the would be god Willy and the new values of the would be human Biff collide in a dramatic confrontation in the parlor of their living room:

Willy: Then hang yourself! For spite, hang yourself!

Biff: No! Nobody’s hanging himself, Willy! Willy! I ran down eleven flights with a pen in my hand today. And suddenly I stopped, you hear me? And in the middle of that office building, do you hear this? I stopped in the middle of that building and I saw—the sky. I saw the things that I love in this world. The work and the food and the time to sit and smoke. And I looked at the pen and said to myself, what the hell am I grabbing this for? Why am I trying to become what I don’t want to be? What am I doing in an office, making a contemptuous, begging fool of myself, when all I want is out there, waiting for me the minute I say I know who I am! Why can’t I say that Willy?

Willy: (with hatred, threateningly) The door of your life is wide open!

Biff: Pop! I’m a dime a dozen, and so are you!

Willy: (turning on him now in an uncontrolled outburst) I am not a dime a dozen! I am Willy Loman and you are Biff Loman! (Biff starts for Willy but is blocked by Happy. In his fury, Biff seems on the verge of attacking his father)

Biff: I am not a leader of men, Willy, and neither are you. You were never anything but a hard working drummer who landed in the ash can like the rest of them! I’m one dollar an hour, Willy! I tried seven states and couldn’t raise it. A buck an hour! Do you gather my meaning? I’m not bringing home any prizes anymore, and you’re going to stop waiting for me to bring them home!

Willy: You vengeful, spiteful mutt! (Biff breaks from Happy. Willy, in fright, starts up the stairs. Biff grabs him.)

Biff: Pop, I’m nothing. I’m nothing Pop. Can’t you understand that? There’s no spite in it anymore. I’m just what I am, that’s all This is Biff’s final act of defiance; a philosophic rejection of the old heroics of transcendence; a rediscovery of a neo-Epicurean vision that is founded upon the truth of the human condition. The real meaning of heroic defiance, as Biff discovers, is ataraxia and reconciliation with finitude. Biff ends where Gilgamesh ends; and both carry the Promethean fennel stock as a gift for human kind.

This, in brief, is the astonishing, liberating perspective that is denied to most, save the most extraordinary humanist heroes–a topic that will be more fully explored in the last chapter.

Heroes like these achieve this knowledge only as a result of traveling quite a long way down an utterly mistaken path. As Aeschylus reminds us:

Too far, too far, our mortal spirits strive,

To grasp at utter weal, unsatisfied.

To review, as we have, the profound and deep-seated power of existential fear, is to know with assurance that religion’s ubiquity and phenomenal persistence derives from the fact that it deals with the future, both immediate and long-term. It is the future, after all, which gene-carrying organisms are charged with breaking into.

From these self-centered origins, religious culture will articulate a system of values that appear to be most unworldly: altruism, selfless giving, and love of an intangible idea rather than things. These are the routes the psyche deploys to secure a winning ticket to life’s heartless lottery.

If neurosis, guilt, ambivalence, and introjected aggression have been selected for in the evolutionary schema, then the altruism which religion and evolution both inspire must have to do with self interest–the maximization of inclusive fitness. Ethical behavior could be explained as a symbolic variation on fundamental, creaturely facts. On the one hand, “we may well have been selected for valuing and approving behaviors that contribute to our fitness: e.g. kindness to friends and relatives and antagonism to strangers” (Barash, 1977). Or as Wenegrat observes: “The religiously inspired altruist believes, in effect, that he has a reciprocal altruistic relationship with God, and that what God wants from him is for him to aid other people…in this, they are modeling god on the basis of real caretakers, whose kin-directed altruistic preferences exert a continuous influence on the child’s moral upbringing” (1990).

But the correlation between religious expression and the ROM of the genetic code was probably never 1:1. The symbolic externalization of an internal code may ultimately slip the collar and, like a wildly racing engine, go beyond creaturely requirements and life’s simple enough rules. The inventive mind has the power to elaborate systems that identified and responded to threats at a wholly phantastical level.

The cultural metaphysic elaborated under these conditions was not obligated to come in contact with the actual ground of life itself–could even be maladaptive. As in Dobzhansky’s formulation, the maps would become less and less useful, and the territory through which an explorer attempted to navigate would become more and more unreal.

For example, the transit of the sun across the sky could be misread as a gigantic promise of salvation.

But what could not be properly understood by the myth makers: the sun itself is on fire. Earth, stars, galaxies were all of them caught in the great entropic dance of creation. The transitory form of each will ultimately be destroyed.

* (While teaching this play 200 or more times during my career, it occurred to me that the name Bill Oliver is made of several interesting components, none described by Arthur Miller. “Oliver” can be separated into O-Live, which is the literal translation of the Egyptian Ankh, the symbol for eternal life associated with the transit of the sun. The sun is gold in color which we equate with money–or if you prefer, dollar Bills. “Bills All Over” (Bill Oliver) sits in his office and is a deity who can restore Biff’s–and Willy’s–failed dreams.)

Next:Schizo Philosophy: The Sirens Beckon Or: Back to Index