.

Schizo Philosophy: The Sirens Beckon

Crito, I owe a cock to Asclepius; please

see that the debt is paid.

Socrates final words, uttered from beneath the sheet that he had drawn over his face to hide the poison grimace, were thought to point the way out of humanity’s existential dilemma:

Crito, I owe a cask to Aesclepiius.

Please see that the debt is paid.

It was the custom in Greece to make an offering at the temple of Asclepius, the god of healing, when one had recovered from an illness. In making this offering of a cock, what Socrates clearly means is that life itself is the illness, and that to die is to recover. To die is to achieve the long awaited release of the soul from the emprisoning bonds of material existence. By the time of Socrates, this mystical, religious belief has become rationalized, and its justifications lie snugly bristling behind a delusional facade of brilliant argumentation.

A post-modern perspective requires us to approach this impediment to humanity’s reconciliation with the facts of life by first recognizing its incomparable beauty. Its roots will draw nourishment from a fatalistic soil, but as in the story of Jack, they will give birth to a magical beanstalk that promises to connect the impoverished earth with the golden treasures of the miraculous giant’s castle. For many it also conjures peace of mind–but it most certainly knee-caps the development of independence and autonomy. This is because it perpetualizes infantilism and surrender to some larger, invisible Other.

Thus at countless junctures upon its obfuscatory journey, the idealist tradition skates perilously close to the edge of the wood–the edge that all along we have insisted we must come to see. The ice is thin; the darkness of the shadowy trunks looms ever closer. But the deft skater salutes, then turns and glides out into the sunlight once again.

For though the idealist tradition is ruthlessly honest in its analysis of the futility of earthly human striving–even the godless can understand that– its primary objective is to lead the believer away from a reality-testing appraisal of the human condition. Where Biff’s failure (Death of a Salesman) leads to a grim resolve to endure in, and attempt to enjoy, the here and now. What you see is what you get: this is the only victory that was ever available to mortals such as Gilgamesh in the first place. So it is that the self-deluding hubris of the Platonism we are about to explore leads to yet another false exit. A larger cave beyond the cave.

Consider these verses from the Upanishads:

Bring hither a fig from there.

Here it is, Sir.

Divide it.

It is divided, Sir.

What do you see there?

These rather fine seeds, Sir.

Of these please divide one.

It is divided, Sir.

What do you see there?

Nothing at all, Sir.

Verily, my dear one, that finest essence

which you do not perceive– verily from that

finest essence this great tree thus

arises. Believe me, my dear one, that which

is the finest essence– this whole

world has that as its soul. That is Reality.

The elevation of “nothing” to the status of a supreme reality is a superb trick, made convincing by the reductionism and logical funneling that prepare the reader to accept the ostensible reasonableness of its conclusion.

To the philosophic Hindu there were two processes in this life–things coming into being, and things passing away. Not even the mountain, which appears to human eyes to be eternal, remains at rest. This first–and last–concession to reality follows the time-honored psychology of argumentation.

What follows is more exoteric. Two gods preside over this dualistic process: Vishnu, god of life and creation vs. Shiva, the god of destruction. And an even more mysterious being resides behind this process and governs its operations. This is Ultimate, identified as Brahman, the eternal ground of all existence.

Though the Egyptians had their Amon–the invisible breath that animates all things–he never achieved the majesty of the Hindu Brahman. For in esoteric Hinduism the gods Shiva and Vishnu were really only projections of the two manifestations of Brahman: Coming into being and passing away.

Brahman endures as an unchanging reality behind this present and human world of perpetual change.

As Shelley described this arrangement in Adonais:

The One remains, the Many change and pass;

Heaven’s light forever shines; earth’s shadows fly;

Life, like a dome of many color’d glass

Stains the white radiance of eternity.

Only the world of matter–called Maya–was subjected to these alterations. Since the nature of the material world is impermanent and unreliable, one must instead live for a transcendent reality that, by its nature, could never disappoint:

How is there laughter, how is there joy,

As this world is always burning?

Look upon the world as you would on a bubble,

Look upon it as you would on a mirage;

The king of death does not see him

Who thus looks down upon the world.

Death and loss are not real because the life in which they occur is itself an illusion. This dichotomy is the central message of the Bhagavad Gita, a text which germinated for centuries in the oral tradition of the Hindu, but which reached its final form sometime in the second or third century BCE.

Arjuna, reluctant to engage in a battle where so many of his friends and relatives are numbered among the enemy, is advised by his charioteer Krishna–an incarnation of Vishnu–to do his soldierly duty anyway. The god instructs him that life and death are mere accidents, illusions really, and that the true part of humanity, the soul, can never be killed.

The American transcendentalist Emerson captured the essence of Krishna’s death-defying message. It is Brahman himself who speaks:

If the red slayer thinks he slays,

Or if the slain think he is slain,

They know not well the subtle ways

I keep, and pass, and turn again…

Consider an analogy: a kettle of pea soup. Turn the burner on high and soon bubbles rise up onto the surface; each having its little life, then expiring in small explosions that release tiny clouds of steam. Though the bubbles come into being and pass away, the soup nevertheless remains. The bubbles are the Many individual lives; the soup is the One source from which all life rises: Brahman. This One Reality remains, despite the innumerable, superficial changes that occur on the turbulent surface.

The Roman neo-Platonist Plotinus would call the expiring of the bubble “the flight of the alone to the alone” –or the becoming one with the One. But while the physical self was thought to be a constricting envelope that separated the devotee from true reality, the intra-psychic fundamentals of his philosophy point to self boundedness. The oceanic experience, touted by Plotinus as the experience of god, comes from within: “the mystic pretends to discard his sensory self in order to meld with the cosmic Self; but in discarding his senses he abjures his only connection with the cosmos and narcisistically re-encounters only himself. The realities he expounds are inside him, not outside in the world. He reveals only inner space, not outer space, in his revelation” (Labarre, 1980).

Derived itself from the mythological paradigm of the cosmic journey, Plotinus’ theory of knowledge is predicated upon an ascending, descending–and hierarchical– movement:

0 Agathon

000 Noesis

00000 Dianoia

0000000 Eikasia

000000000 Pistis

At birth the child loses the unitary vision (Agathon) and is sentenced at once to fall downward into the material world. The first knowledge of the world comes in many bits and fragments–unassociated impressions represented by the level Pistis. As the child ages, these simple impressions are associated into simple ideas; and simple ideas are later combined into complex ideas–represented by the decreasing number of zeroes (the Many) as one moves slowly up the pyramid. Agathon remains a dim–and sometimes completely blurred–recollection of the unitary truth of things, and though most human beings remain stalled somewhere near Dianoia perhaps, some few sages complete the ascent and achieve the mystic vision of the One reality. One wonders what Foucault, the chronicler of fecund diversity, would think of this overwhelming predilection for the meta-narrative; the triumph of which would mean the end of any and all dialectic.

Plotinus would have us believe that birth is a fall from perfection, and that the true course of life is itself also a progressive movement back (this is a contradiction) to the primary vision of childhood–to the elemental and undifferentiated oceanic experience of oneness. Humans come from the realm of the eternal at birth, and the rest of one’s life is either a continual falling away from that standard–being stuck in the Many–or a return to a profoundly anti-intellectual wisdom: a renunciation of the reality of this material world. The person who would be wise must begin, through acts of mystic contemplation– not entirely unlike that which Bernini shows us in his St. Teresa–to ascend the pyramid, somehow shedding material knowledge and encumbrances along the way–another contradiction.

This, of course, is a credo of the mystically inclined type of romantic– the Shelley of the Adonais as well as the Wordsworth of the Immortality Ode. But the journey is extremely difficult, especially as the material world tends so effectively to block that primal vision of the truth that is inborn into human consciousness– a priori. As the law of life is that one must age, so one must necessarily forget or lose that vision of the truth:

The youth, who daily farther from the east

Must travel, still is nature’s priest,

And by the vision splendid

Is on his way attended;

At length the man perceives it dies away,

And fade into the light of common day.

(Wordsworth)

We can see just how Hindu this idea is, especially as it elevates nothing to the status of something, and avowedly inverts scientific or reality-testing notions, trans-valuing experiential knowledge as ignorance.

To return to Agathon is to approach divine, ideal reality. It is to transcend the pettiness of material existence where humanity is continually harassed by questions having to do with what it shall eat, and what it shall wear. From the vantage point that Agathon endows, all material divisions are reconciled and melded into a universal mosaic of truth, a vision that Hesse bestows on his Siddhartha when he arrives at last at the river:

“He looked lovingly into the flowing water, into the transparent green, into the crystal lines of its wonderful design. He saw bright pearls rise from the depths, bubbles swimming on the mirror, sky blue reflected in them. The river looked at him with a thousand eyes–green, white, crystal, sky blue…but today he only saw one of the river’s secrets, one that gripped his soul. He saw that the water continually flowed and flowed and yet it was always there;it was always the same and yet every moment it was new.”

This fusion with the maternalized ego-ideal (Chasseguet-Smirgel) provides the antidote to the pain of human existence, for it teaches that despite the many losses one rings up as one moves through life, despite the ultimate triumph of time which causes all wishful bubbles to burst, some aspect of the much-loved self does continue. If one cannot possess the material world– which itself is an illusion– so much the better. For to divorce one’s self from matter and to lead an ascetic existence is to begin to move closer to god, to truth, to Brahman.

But as Freud and other critics have pointed out, such idealistic self-denial is a masochistic affirmation of a primary narcissism. It is also infantile in that it fetishizes the return to the womb; to the oceanic and omnipotent domain of the infant suckling at the breast. It is also, in the following formulation, more than a little self-serving: the world of matter is evil only because it does not obey, immediately and magically, the infantile wish…Narcissism finds it `hostile.’ Materia is the `bad mother,’ the world is evil, the world is an illusion” (LaBarre, 1970).

This is the unconscious reason why saints throughout the ages have found it necessary to renounce the world and the flesh in order to free the spirit for its higher pursuits: Buddha leaving his princely palace behind, St. Francis giving his fine clothes to beggars and going out naked into the world, St. Benedict, afraid that his lustful thoughts will deny him entry into paradise, leaping naked into a blackberry thicket and thrashing about until he relearned the lesson that the way of the flesh is the way of pain.

We also see the sad fruits of a later derivative of this self-hatred and denial in Hawthorne’s novel, The Scarlet Letter. The natural equation “Man, Woman, Child” is transformed into a hateful, guilty thing by this metaphysic. In a belief system like this, Thanatos masquerades as love.

But one must strive after this purity; it is not simply given as a gift. Brahman has placed a veil between himself and the material world. It is only through renunciation of the imprisoning flesh that the sage can begin to see through this veil; can contemplate life, as Spinoza has said, sub speciae aeternitatis–as an aspect of eternity.

One fantasied result of a worldwide ego death would be that a peaceful ethic would at last reign triumphant, and the sibling rivalry against which parents have always had to struggle would give way to the induced altruism insisted upon by parental investment equations (Badcock, 1990). The petulant, desiring, egocentric self will at last be seen to be illusory– that same self which is so easily wounded or enraged, and which fuels some of the most destructive emotions.

A post-modern perspective informs us that this transcendence of hubris is its own kind of hubris. The metaphysic behind pursuit of the higher goal is based upon a denial and rejection of one’s creaturely nature.

How odd that this ethic, which has as its core not only a love for the beyond but also a profound hatred for the here and now, would later provide much of the philosophical background for European romanticism, that varied philosophy which in some forms celebrated not only life and nature, but which paradoxically also raised the value of the “I,” the ego, to unprecedented heights. The hubris of the saint, however professedly pious, is only more subtle than the hubris of a dictator, not less powerfully present.

As Nietzsche’s Zarathustra said:

I adore the great DESPISERS:

They are arrows, longing for

the distant shore.

This need to discover an antidote for the evils of this world is also the means by which the devotee can achieve distinction: for as the world and its processes are diminished and rejected, the self must necessarily grow in moral superiority. This is why a romantic such as Wordsworth goes to nature, or why Thoreau goes to Walden. To leave civilization behind is to leave behind the mad pursuit of wealth, and to hear, behind the still voice of nature, the eternal voice of god or the absolute:

The world is too much with us;

Late and soon, getting and spending

We lay waste our powers;

Little we see in nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away,

A sordid boon!

(Wordsworth)

It is to be singled out as one of those who does hear; as one of those who righteously escapes from the error that the rest of humanity has fallen into; and as one of those to whom the god speaks. A certain amount of overvalued self-regard is required to convincingly ascend the pulpit, to climb the steps of the pillory, to wear the hair shirt, or to bear the weight of the cross on the pathway to the Hill of Skulls.

That civilization itself is corrupting is a cardinal principle of the idealistic wing of the romantic view. For if one’s true essence is spiritual, then to participate in and believe in this material existence is to fall, not rise. To live and revel in matter is to become dead to the existence of a higher reality, and to begin that fateful journeying from the east, or that descent down the Plotinian Pyramid and away from Agathon:

Our birth is but a sleep, and a forgetting;

The soul that rises with us, our life’s star,

Hath somewhere else its setting,

And cometh from afar.

Not in utter nakedness, and not in entire

forgetfulness; But trailing clouds of

glory do we come from god, who is our home.

“Setting” in Wordsworth’s marvelous ode has a double meaning here. One is that the soul has a destination quite different from that of the body which returns to the dust from which it arose, and two, that the body is a poor setting for the jewel of the soul. The two are alien to each other, and only forced into this weird marriage by cosmic circumstance. Thus continues humanity’s infatuation with conflictedness and self-division: “the world of bodily experience inevitably appeared as a place of darkness and penance, the flesh became an ‘alien tunic’…[and] the body was pictured as the soul’s prison, in which the gods keep it locked up until it has purged its guilt” (Dodds 1973).

Thoreau and Wordsworth both believed that human beings were “born as innocents, but polluted by advice.” Material civilization was a distraction; an imprisoning cave full of the tantalizing shadows that this dirty whirler of a world uses to distract one from the pursuit of the truth. The more one knows, the less one knows. Less, therefore, is more:

Shades of the prison house begin to close

Upon the growing boy…

And the earthly world of man:

with something of a mother’s mind,

and no unworthy aim,

doth all she can to make her foster child,

her inmate man, forget the glories he

hath known, and that imperial palace

whence he came.

“With something of a mother’s mind…” says the poet in passing. The anti-feminine bias of Platonism and idealism has been often commented upon: the blame attached to woman for the Fall, the association of matter (mater) with the mother from whom the male, as offspring of the pure Logos, must separate. This disparagement of the female passes upward through Plato, into Paul and beyond.

In the foregoing quotation one also sees the modern literary origin of that oft recited, little understood idea that children, in their innocence, are superior to adults who are experienced in the ways of the world. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye puts it this way:

“It’s funny. You take adults, they look lousy when they’re asleep and they have their mouths way open, but kids don’t. Kids look alright. They can even have spit all over the pillow and they still look alright.”

Holden Caulfield, trapped at status conscious Pencey Prep–a place where the quality of a boy’s suitcases is more important for acceptance than the quality of his character–dreams of preventing children from falling from a state of innocence to the corruption of adulthood:

“Anyway, I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around–nobody big, I mean–except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff–I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d like to be.”

To stop the growth process is to go against the laws of nature. It would be a perfect world, but only if one believes that children are the highest and best embodiment of what it is that human beings might become.

For the true meaning of this quest– perhaps best summarized by that Jesus who advised his followers to become little children again if they wished to follow him– is an obsession with regressing to the infantile. It is a secret, subconscious wish to have never been born but instead to remain within the womb.

This denial of the possibility of progress is a thinly disguised cry of fear: the fear of dying. As the ancient self can plainly see, mature science can only produce doubts about the metaphysic of continuance. The child in the womb need confront none of this, for ignorance is indeed bliss:

One impulse from a vernal wood

Will teach you more of man;

Of moral evil and of good

Than all the sages can. (Wordsworth)

Having gone off to Walden from whence Henry issues pronouncements on the current state of the world, Waldo, in exasperation, erupts:

“And what are you doing about (the evils in the world) young man? You pull the woods up over your head. You resign from the human race. Could your woodchucks, with all their wisdom, have saved Henry Williams (from slavery)? Are your fish going to build roads, teach school, put out fires? Oh, it’s very simple for a hermit to sit off at a distance and proclaim exactly how things should be. But what if everybody did that?”

(Lawrence & Lee Night Thoreau Spent in Jail)

Of course Waldo is right about the dangers of withdrawal, for the law of life that demands involvement is the most ancient of natural rules. But Waldo needs to be fair also. Thoreau is necessary as a Socratic gadfly, and to the extent that he is able to remind adults of what they have lost as a result of their obsessive surrender to the world, he is performing a valuable service.

Again, the skater moves perilously close to the shadow-filled wood.

So much of what Thoreau says is right on the mark, and at last the circuit of his intellectual journey does return him to the earth after all.

Yet, one can see the ultimate, lopsided extension of this idea in the arrested development of the citizens of Brave New World. Perpetually entertained, anxiety-free, middle and lower classes immeasurably shallow, never questioning the fundamental assumptions of their culture, the citizens of Huxley’s world function as so many worker bees, blissfully existing for the good of the state, blindly trusting that their way of life is good.

Their lives are enmeshed in man-made certainties which help solidify their cosmic connectedness, and which make them blind to the evils of their world. They have, in short, the good breast, supplemented by seashell earpods that continuously stream soothing music and conformist messages.

Huxley’s character John Savage is their foil–just as infantile as the mystic, but furious that he has gotten the bad breast instead of the good.

There is a truth that centers itself between these oscillating extremes. This is the knowledge that the attribute that separates humanity from the rest of living creatures is its applied intelligence, its capacity to know, to build, to shape its world to suit its needs. Cast in other terms, one might characterize this as a potentiality to aestheticize experience as well: to derive manifold and subtle pleasures from the contemplation of action and experience in the evanescent world of physical phenomena.

But it is at precisely this moment that a life can be full–as full as it can possibly be–that the urge to reach for more intrudes itself. The materials of life and earth themselves–the materials which interact with mind to produce an aesthetic contemplation of the journey upon which all creatures are embarked–are seen to be insufficient. It is at this point that the servant mind elaborates a metaphysic that calls upon its adherents to renounce life in the here and now in order to retreat from evil.

More amazing is the ease with which persons holding these opinions move through life apparently unconflicted. One is always astonished by worldly individuals who profess to believe in a god or gods whose teaching condemns their own gluttonous participation in that same world. Ossenberger, the wealthy undertaker of Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, simultaneously shifts his Cadillac into second gear while praying to Jesus to send him more stiffs.

The world is full of such phonies, as Holden would describe them. But modern individuals cannot return to the polymorphous perversity of nature and be Christian at the same time– for its god and nature had been irrevocably cast as antagonists. As the Puritans well knew, Satan and the beasts inhabited the forest.

Long ago, the pagans co-opted the return to nature, rendering it a minefield that would be fatal for Christians to enter. A very old myth of Hercules and Antaeus tells that when the feet of Antaeus leave the ground, he loses his strength. Hercules wrestles with Antaeus, lifts him off the ground, and is thereby enabled to destroy him. The further one gets from natural rhythms and power sources, the myth tells us, the weaker one becomes.

What bloodless metaphysic of sensual and passionate self-denial can embrace a truth-threatening message such as this?

And so we can recognize the beautifully pagan roots of the romantic idealist’s infatuation with nature. Basking in the solitude of some Yeatsian Innisfree, one can at last hear the toneless threnody which has:

Power to make our noisy years

seem moments in the being of the

eternal silence.

(Wordsworth)

And now we discover a comprehensive theory of evil. Most humans want material things, believing them to be both real and the source of happiness. Like salmon pursuing the silver lure, mistaking the false, whirling metal and glass beads for the real thing, the idealist’s less spiritual conspecifics are hooked and destroyed –doomed by their own desires to continue as prisoners in the world of maya; doomed to continue to repeat their errors in successive lifetimes until they, too, can learn to renounce the material world and become one with its immanent god.

Structured as it has been so far, the problem itself seems to perpetuate its continuation. Caught between the antipodes of all or nothing, between the good and the not good, what can mere creatures do to rescue themselves? The enjoyment of the world of matter is tainted, and the enjoyment of the spiritual quest is debilitated by the fact that it is launched from a platform of insufficiency and guilt–a foundation built upon shifting sands.

And so it is that the metaphysic of transcendentalism is self-defeating. It takes a simple enough value and then gratuitously embellishes it, fearing that the sense contained within the message to live simply and well was not powerful enough to compel. Thoreau’s doctrine that “less is more” needs no transcendental trappings, and is founded on the simple truth that to own more things is often to become more owned–enslaved by the costs that are incurred in maintaining one’s properties and machines.

Everyone who loves his Walden remembers his description of the “successful” farmer wheeling his possessions as well as his seventy-foot barn down the road of life, staggering under the sheer weight of such prosperity. Not even the millions of a later Great Gatsby can assuage the fundamental unhappiness that resides within the inner man. Not even a membership in the college of cardinals would suffice. But this too is knowledge that comes from earth–it is self evident and derived from the world of experience. As such, its truth value can only be further obscured by gratuitous metaphysical elaboration.

As Happy observes in Death of a Salesman:

“All I can do now is wait for the merchandise manager to die. And suppose I get to be merchandise manager? He’s a good friend of mine, and he just built a terrific estate on Long Island. And he lived there about two months and sold it, and now he’s building another one. He can’t enjoy it once it’s finished. And I know that’s just what I would do. I don’t know what the hell I’m workin’ for. Sometimes I sit in my apartment–all alone. And I think of the rent I’m paying. And it’s crazy. But then it’s what I always wanted. My own apartment, a car, and plenty of women. And still, godammit, I’m lonely.”

But Arthur Miller, as we have seen, did not invent this motif; and neither did Lucretius, who describes much the same problem nearly two thousand years earlier:

“…If, just as they are seen to feel that a load is on their mind which wears them out with its pressure, men might apprehend from what causes too it is produced and whence such a pile, if I may say so, of ill lies on their breast, they would not spend their life as we see them now for the most part do, not knowing any one of them what he means and wanting ever change of place as though he might lay his burden down. The man who is sick of home often issues forth from his large mansion, and as suddenly comes back to it, finding as he does that he is no better off abroad. He races to his country house,driving his jennets in headlong haste, as if hurrying to bring help to a house on fire: he yawns the moment he has reached the door of his house, or sinks heavily into sleep and seeks forgetfulness, or even in haste goes back again to town. In this way each man flies from himself.”

Happy’s brother Biff recognizes the killing effects of civilization, and at the end of the play sets out for a job as a hand on a Texas ranch–a decision that will probably guarantee that he shall be rather poor, but at least relatively free of the pressure to succeed at someone else’s game.

But as we shall later see, Biff’s return to nature is post-modern and rational, not ideal. For despite the mythology of the idealists, the simplicity of natural law speaks with another voice: Siduri’s vision of the finite and the real. Biff wants the time to “sit and smoke,” not to contemplate god.

Which brings us up alongside the discovery of the Buddha. Where the esoteric (not exoteric) Hindu was patient, tolerant of human shortcoming, of the need to become wise by making all the mistakes in all the lifetimes, and in leisurely fashion at that, Buddha was impatient, and brought the doctrine of renunciation to a fine pitch. But the renunciation he preached was total, and called for his students to abandon their personal immortality project as well as their pursuit of wealth.

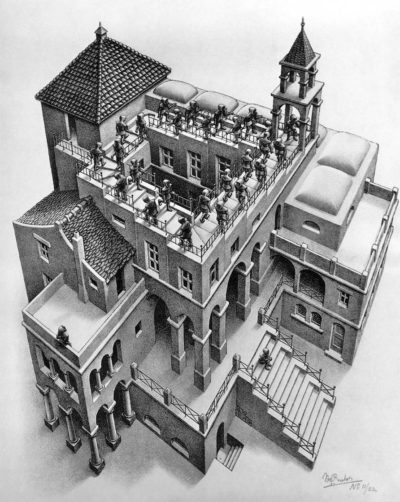

How well Escher and Siddhartha Gautama might have gotten along remains a matter for speculation; but it is certain that our saint would have appreciated the artwork with which we began this journey, seeing in it a confirmation of his own answer to the dilemma of human history.

Of all the teachers of the world, the Buddha will come closest to sharing our thesis; though he will ask humanity to renounce something different in order to break free from the ever spiraling historical round–a goal which most practicing Buddhists do not share with their founder.

A post modern view starts from the position that life is worth living, and that in order to be free and happy, as in Epicurus’ formulation, it is necessary for one to renounce imaginary connections to the gods and to face death squarely, thus driving it out from the invisible corners where it may assert an untoward influence upon human belief and behavior.

But the Buddha reviles life itself, and asks humanity to renounce not only these, but also this earth as well. What one should seek instead is annihilation. According to Buddha, the scheme of life is futile and circular, just as in the Escher print: birth, life, death–all fueled by human desire.

Crassus, I suppose, is the supreme example of this kind of destructive ambition to acquire. Already the richest man in first century Rome, he nevertheless clamored after more honors, finally seeking and securing the command of an expedition against Parthia, all in an effort to equal the status of his rivals Caesar and Pompey. The expedition turned out to be a spectacular disaster– his son Publius was captured and beheaded in the first engagement with Surena’s troops– and Plutarch shows us the great man on the eve of the final, futile battle, unable to rouse his soldiers who had marched into Parthia with such bright confidence, and now himself convinced of his own doom.

He sat by the fireside, “wrapped his cloak around him, and hid himself, where he lay as an example, to ordinary minds, of the caprice of fortune, and to the wise, of the inconsiderateness of ambition; who, not content to be superior to so many millions of men, being inferior to two, esteemed himself lowest of all.”

But now we come to the darker dimension of Buddhist teaching, a teaching not unlike that embodied in the doctrine of Armageddon. Life is sick, says the extremist Christian from his self-imposed exile, or the Buddhist from his meditative lock-up. For both, the world was seen to be a perpetual cycle of evil and suffering–this was the lot of all flesh– but the only antidote was to utterly renounce this existence and long for death.

A later Socrates comes perilously close to sharing this pessimistic desperation. But one must also recognize that in the person of Socrates the student still sees an admixture of the saint and the politician; one who like a Buddhist is almost ready to give up on the world and on life, but one who also has devoted himself to reforming it by arguing with its citizens.

He develops both points of view at his famous trial: “Be sure of this, that if you put me to death, being such as I am, you will not hurt me so much as yourselves…Now therefore, gentlemen, so far from pleading for my own sake, as one might expect, I plead for your sakes, that you may not offend about God’s gift by condemning me. For if you put me to death, you will not easily find such another, really like something stuck on the state by the god, though it is rather laughable to say so; for the state is like a big thoroughbred horse, so big that he is a bit slow and heavy, and wants a gadfly to wake him up. I think the god put me on the state something like that, to wake you up and persuade you and reproach you every one, as I keep settling on you everywhere all day long.”

But suddenly the critical and clever philosopher reveals his contempt for the world as well, as if he is of two minds about the wisdom of attempting to save it: “Perhaps it may seem odd that although I go about and give all this advice privately, quite a busybody, yet I dare not appear before your public assembly and advise the state…Do not be annoyed at my telling the truth; the fact is that no man in the world will come off safe who honestly opposes either you or any other multitude, and tries to hinder the many unjust and illegal doings in a state. It is necessary that one who really and truly fights for the right, if he is to survive even for a short time, shall act as a private man, not as a public man.”

Here the saint has almost, but not quite completely, given way to the pessimist, or to the editorialist.

Next: Plato’s Counter Reformation: Attacking Reality Or: Back to Index