Erda’s Ring: Sleep Tight, Wotan

The great wheel spins, turns away from itself, twisting the strands of moments into one continuous thread of time. The shuttle clatters as the thread–always the same thread–is worked into the tapestry of life.

Camped by the great world tree Ygdrassil, the Norn sisters weave the fabric of the future: A Wyrd that is clear and predictable to any who might read it. Held fast within its warp and woof, each of us appears on the tapestry. See the tightly spun threads of our lives plotted, calculated and projected into the future.

Moira is one of the many names for the destiny that rules both men and gods. This allotment cannot be resisted: it will bring mortal Oedipus to ineluctable ruin, and it will make a much later Macbeth wish he had never encountered the Wyrd Sisters.

Not even the gods are safe from its operations. As Aeschylus shows us in his Prometheus Bound, even Zeus himself will be unable to “shun the lot apportioned.”

Angered that Prometheus has stolen fire from Olympus and given it to humans, Zeus chains the Titan to the craggy face of Mt. Caucasus. But though vultures return daily to devour his flesh, one spiteful solace remains: He has learned that fate’s resistless law has decreed even the death of the gods themselves. Despite the agonies of his punishment, Prometheus feels triumphant, and will not reveal the details of his knowledge to Zeus or to his messenger Hermes– preferring instead to hint darkly at this doom so as to more fully torment his tormentor.

Other gods face such a twilight as well, and how like you and I they seem when they confront a fatal inevitability. In one famous variation–Wagner’s Das Rheingold–Loge, Norse spirit of fire, hints at the doom of the gods. He alone can sense their fated demise by the end of the first opera of the Ring: Gotterdammerung.

Wotan, Norse counterpart of Zeus, finds himself in a tightening vice of circumstance. First among the gods, this powerful Father should be at ease, having just witnessed the completion of his heavenly fortress, Valhall: The "Fort I have founded to banish all fear."

Its builders, the giants Fasolt and Fafner, now demand the payment stipulated in their contract with Wotan: this is the exchange of Freia, goddess of youth and the Golden Apples of eternal life, for the finished palace. Of course the terms of the secret contract–the barter of a female agreed to in private among the thick skulled men– surprises and outrages both Freia and her elder sister Fricka, Wotan’s wife. But much more than his domestic peace will be ruined if he doesn’t find a way out of the ill-advised bargain.

At first Wotan considers rescinding the agreement; he is, after all, a god. But the giants remind him that to go back on his word is to undermine the foundation of his authority: the trust that is his sole prop to power in the universe. The other alternatives that Wotan contemplates are just as bad. To give up Freia to the giants is to exchange divine immortality for mortality and so bring about the death of the gods.

It is at this point that clever Loge informs Wotan that there is one other payment that might suffice. Far below the surface of the world there resides a race of dwarfs– the Nibelungs. Their tyrannical master, Alberich, compels them night and day to pile up gold to satisfy his greed. What is more, he has only recently stolen the precious Rheingold from its guardians, the Rheinmaidens.

From this treasure Alberich has forged the Tarnhelm and the Ring– both of which have the power to confer world mastery and immortality on their owner. What a boon it would be for the gods to steal these, as well as the Nibelung gold horde! Some could be used to pay for Freia, and remainder of the miraculous cache known as the Rheingold could be returned to the maidens as well, the gods keeping only the Tarnhelm and the Ring for themselves.

Wotan persuades the giants to accept the Nibelungen gold horde in Freia’s stead. The only trouble is that it must be stolen from newly formidable formidable Alberich before it can be handed over. In one of opera’s great scenes, Wotan and Loge enter a mountain cleft and begin their spectacular descent to the underworld– accompanied by the rhythmic hammering of eighteen specially tuned Wagnerian anvils.

They return successful, and the giants bid the gods to heap up a hill of gold large enough to block their view of the goddess whom they must surrender. But the gold runs short, and one of the giants can still spy Freia through a chink in the pile. Quickly they notice the Tarnhelm and the Ring which the gods have carefully set aside. Cunningly, they demand that both miraculous treasures be thrown onto the heap in order to block Freia from view.

Yet again, Wotan finds himself forced into a fatalistic, no-win dilemma. To keep Freia is to lose his authority; to give up Freia is to relinquish his immortality; to exchange Freia for the Ring and the Tarnhelm is to set up dangerous rivals to his own mastery and power.

Finally, Wotan resolves on the latter course, hoping that by trickery and other means he will ultimately be able to wrest the ring and tarnhelm from the giants. But as the opera comes to its troubled conclusion, we learn that the far-seeing Loge knows better. He knows that the gods can not ever be saved.

In a moment of climactic irony, Donner hammers away the storm clouds and a Rainbow Bridge opens up, inviting the gods to cross from this conflict ridden, dwarf and giant cursed world to the security of their newly built palace Valhall. But as they begin their triumphant processional, Loge and others in the party become conscious of the Rheinmaidens’ mournful pleas to restore the stolen gold.

Their plaintive voices rising from the chthonic depths of the Rhine, they are the fatalistic counterpoint, reminding Loge of the doom that awaits even these super-masculine, shining beings:

Now behold them haste to their end,

while they fancy their being immortal!

Despite his heroic exterior, Wotan becomes even more troubled. Just moments before this divine blast-off, Erda, earth-spirit and the mother of the Norns, warns Wotan to beware: the apportionment of destiny is something no one, not even a god, can oppose or overthrow.

Spellbound, the gods watch in horror as she rises from the underworld to deliver her intimidating prophecy from the heart of a bluish flame:

Hear me! All things that are, perish!

A mournful day dawns for Valhalla.

And so Wotan, a powerful but suddenly incompetent male divinity, feels the grim decree of necessity –symbolized in both stories by a ring– encircling both himself and Valhall, the fort he “had founded to finish all fear.” Not even a subsequent attempt to beget a race of heroes to undo the evil coils of his fate can save him from Gotterdammerung.

Later, there will be many such sons of god. More often than not their task will be to unravel the snarly mesh-work that binds the will of the father. But as we shall later see, a few–just a few–will choose another path in order to keep their obligatory appointment with destiny.

2

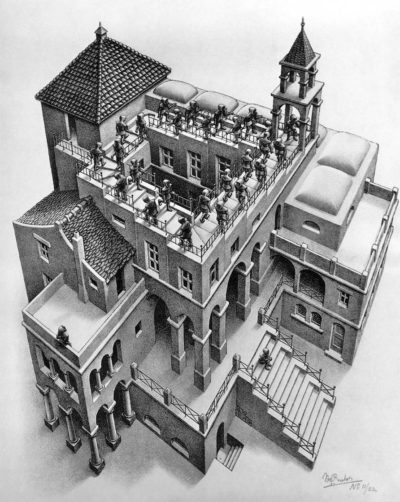

Heroes. Gods. Rainbow bridges. We mortals lead much less spectacular lives. Rising less high than the gods, we have a shorter distance to fall. But we too have our Erdic prophecies of doom, and we build our own psychic and material fortresses to banish fear. Like the cowls that blind Escher’s monks, these psycho-cultural defenses against the inevitable will be designed to keep us so preoccupied that we will not notice when at last it arrives.

The first and foremost fact of life is that no one, however powerful, can banish death. Our appointment with that destiny is unavoidable.

But unlike Orestes, who at least had the satisfaction of knowing he was important enough to be pursued by the spectacular Furies, most humans must instead recognize the image of their fate in the trivial, the de-mythologized, the ordinary:

I have gone into the waste lonely places

Behind the eye: the lost acres at the edge of smoky cities.

What’s beyond never crumbles like an embankment,

Explodes like a rose, or thrusts wings over the Caribbean.

There are no pursuing forms, faces on walls:

Only the motes of dust in the immaculate hallways,

The darkness of falling hair, the warnings from lint and spiders,

The vines graying to a fine powder.

There is no riven tree, or lamb dropped by an eagle. (Roethke)

Or in the words of Auden's Musee des Beaux Arts:

About suffering they were never wrong, the Old Masters.

How well they understood its human position:

How it takes place while someone else is eating,

Opening a window, or just walking dully along.

They never forgot that even the dreadful martyrdom

Must run its course, anyhow, in a corner:

Some untidy spot where the dogs go on with their doggy life,

And the torturer's horse scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

Gods and goddesses, Escher’s monks, ourselves: a fatalistic tradition binds us all, and presents us with an image of ineluctable circularity, a joining of ends and beginnings, a convergence of the mythic and the real. For the “end,” once foreknown, compels the trajectory of our lives to pursue a predictable orbit at last: We begin in darkness, and to darkness we shall return.

Space is not linear, but curved.

If this is true, the universe might resemble a nautilus, an ever spiraling Escherian complexity–or to change the image, a celluloid film that at first glance appears linear, but whose secret essence is the reel–a wheel or “ring” whose rotation can play, replay and reverse all the moments catalogued in time.

Vonnegut’s Billy Pilgrim has just such a vision in his space dream of the fire-bombing of Dresden in World War II:

"American planes, full of holes and wounded men and corpses took off backwards from an airfield in England. Over France, a few German fighter planes flew at them backwards, sucked bullets and shell fragments from some of the planes and crewmen. They did the same for wrecked American bombers on the ground, and those planes flew up backwards to join the formation. The formation flew backwards over a German city that was in flames. The bombers opened their bomb bay doors, exerted a miraculous magnetism which shrunk the fires, gathered them into cylindrical steel containers, and lifted the containers into the bellies of the planes. The containers were stored neatly in racks. The Germans below had miraculous devices of their own, which were long steel tubes. They used them to suck more fragments from the crewmen and planes. But there were still a few wounded Americans, though, and some of the bombers were in bad repair. Over France, though, German fighters came up again, made everything and everybody as good as new. When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating night and day, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals. Touchingly, it was mainly women who did this work. The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground, to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody ever again. The American fliers turned in their uniforms, became high school kids. And Hitler turned into a baby…Everybody turned into a baby, and all humanity, without exception, conspired biologically to produce two perfect people named Adam and Eve, he supposed."

Time returns each of us again and again to the home; to those first parents whom we must always leave behind, and whom we must always, inevitably, both return to and become.

This image of doom and futility is at first humorous, but ultimately terror filled. It is humorous because to run the loop backward is to reduce the significant (World War II) to the absurd (Hitler as a baby). It is terror filled because the contrast between the innocence of infancy, the tenderness of maternal care, the sanctity of the home, are surrealistically incompatible with Auschwitz, Babi-Yar, bodies impaled on barbed-wire or bulldozed into pits, or the bombing of London. Hitler began as a child; so did we all.

Vonneguts’ words force our faces into the contemplative mire; his words insist that we recognize our enslavement and powerlessness; our kinship with the insect in the amber.

For however much one’s rational self may decry the folly and brutality of the past, humanity still seems incapable of breaking with that pattern.

The script for the modern world seems to be written by an ancient hand; a hand that propels modern human beings even now along the familiar, murderously circular path of national and political life. It is a script which emphasizes human powerlessness to achieve something lasting, as well as human powerlessness to break the bonds and rituals of its imprisonment:

It has happened before.

Strong men put up a city and got

a nation together,

And paid singers to sing and women

to warble: We are the greatest city,

the greatest nation,

nothing like us ever was…

The only singers now are crows crying,

“Caw, caw.” And the sheets of rain

whine in the wind and doorways.

And the only listeners now are…the rats…and

the lizards…

(Carl Sandberg)

It is a script whose secret resides, like some gold-guarding Wagnerian dragon, at the core of humanity’s most profound and ancient myths.

Two of these are the stories of Sisyphus and Tantalus. As all the world knows, one is sentenced for eternity to roll a stone up a great hill. Yet each time he makes it to the top, it pitches over the other side and rolls depressingly to the bottom of the slope. This is Sisyphus’ punishment in the afterlife, and he must trot after it, continuing the unvarying, exhausting pattern to the end of time.

Tantalus is sentenced to an equally peculiar torment. His arms bound behind him, he must stand chest high in cool, clear spring water. Yert each time he bends to drink, the water level drops; and each time he reaches with his lips and teeth for that bunch of grapes constantly brushing against his face, a gentle breeze wafts it just beyond reach.

How cruel to want so much and not to be able to have; how terrible to see no successful end to one’s arduous labors!

What especially moves us about these stories is that they serve as an exaggerated microcosm for the way life really is. The lifelong Sisyphean labors of ordinary men and women, of teachers, poets, housewives or revolutionary leaders to achieve some Tantalizing goal can in a moment be cancelled by the nature of things. Death, self-defeating personal flaw, machinations of power brokers, fake news attacks, the perpetual wars for conquest that grind up individuals as well as nations– even the inexplicable disease or freak accident that strikes the undeserving or the unaware. All seem bent upon demonstrating the ultimate fragility of human striving. And even if one is a winner who rises to world hegemony and averts tragedy time and time again…still, that person, that nation, must ultimately fail to prevail; must die.

Is all this “evil” a gift from the gods to test or to punish humankind for some forgotten transgression? Or is this evil merely a necessary part of the fabric of an indifferent universe; a random, un-aimed blow and thus not really evil at all? How we answer this question is of utmost importance--and the answer that a culture arrives at creates the limits and possibilities of the lives of all those who inhabit that culture.

Let us begin to investigate the labyrinthine pathways of the problem, following, like an earlier Theseus, the threads supplied by Ariadne to guide him out of the maze after his confrontation with the Minotaur.

But to inquire into the warp and woof of the nature of things–a fabric woven from the threads of choice, destiny and necessity– is to embark upon a journey that will cause us to be led both backward as well as forward.

If we are courageous, if we are patient, we shall confront at last the designers of Escher's Staircase.

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go, and make our visit.

(T.S. Eliot)

Next: Panopticon: Welcome to Your Portablee Prison Or: Back to Index