Prometheus, Satan & Jesus

Whether the universe is the intentional work of a designer, or whether it is the result of a blind, spectacular concatenation of processes, cannot be known.

Perhaps only atheists would be satisfied with the latter choice. Atheists do not clamor for cosmic certainty, they do not pray for salvation, neither do they hang their hopes on the existence of an eternal life. It is enough to enjoy the awe and majesty of existence on its own merits. It is enough to accept that death is merely a return to the darkness from which we all first emerged. In the words of Dylan Thomas:

“…Wise men, at their end, know Dark is right.”

Such a conclusion is not satisfying for most people. After all, it is difficult to snuggle up to a blind, careless universe–a phenomenon that cannot be understood, that cannot be communicated with, that cannot be placed under some measure of human control.

They know that a belief in the existence of gods can only be based upon faith, not upon evidence. Faith is defined as the belief in something for which no conclusive evidence exists. And yet, millions around the world do believe in the existence of gods.

What seems clear, therefore, is that the gods have been created by humans in their own image and likeness–not the other way around. It was simply a necessity to do this. It’s the inevitable, most natural way to cover up the wounds of uncertainty. By these means, this unacknowledged act of inventin promises to give believers some measure of control over the mystery of existence.

The gods are now ubiquitous, and have been created in abundance. They have been give names, many of the have been given humanoid divine families, and like humans, they often have semi-divine competitors and challengers.

Like our parents, the gods can be variously portrayed as: generous, selfish, nurturing, indifferent, brutal, tender, life affirming or murderous. They are humans writ large, and share all the strengths and weaknesses of their human creators.

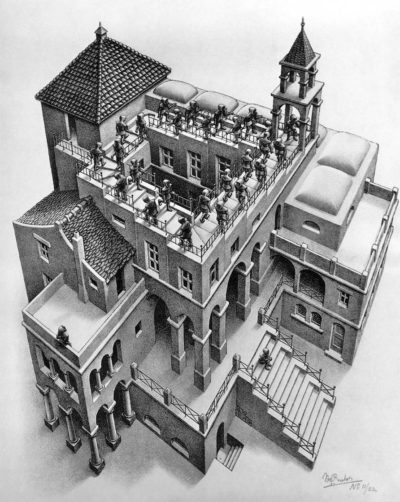

The stories of Prometheus, Satan and Jesus are perfect examples of this phenomenon–and these are not pretty or uplifting stories by any means. Each, in its own way, is built upon a variation of the Stockholm Syndrome–a phenomenon Freud called “identification with the aggressor.”

Prometheus, Satan, Jesus: Hell on Earth

Despite its indebtedness to its pagan ancestors, Christianity’s signature was to be a strict authoritarianism derived from revealed Word. And what the Word emphasized was the penalties for disobedience or failure to surrender to dogma. Its argument was framed from the viewpoint of the Primal Father, and it served as a warning to all rebellious sons.

The joyousness that existed in Christianity could sometimes be ecstatic. But its ecstasy was not Dionysian. Instead, it was an endorphin rush released by surrender to a powerful Aggressor: a divine judge who threatened to damn all those who failed to abandon their natural drive to individuate.

Yahweh often demonstrates that he was not to be trifled with. He also demonstrated, via the mythic Flood, that he possessed a capacity for a mass punishment and terror unrivaled in mythology. But there was hope, and human surrender to divine commands was to become the anodyne. Abject obeisance opened up a pathway to forgiveness and safety. A believer’s ability to escape from divine terror produced an ecstatic fervor, an enthusiasm which can still be seen today in select Black American and a few Evangelical churches.

Christian emphasis on the importance of obedience and taboo were derived from its Hebrew origins. Judaism had originally hit upon these controls as a means of seeking protection against a hostile world. Struggling to maintain their racial identity, the Hebrews found it necessary to insulate themselves from barbarian inundations by prescribing easily measured ritualistic practices that produced group cohesion–what Freud characterized as “the Narcissism of the minor differences.”

But though Christianity broadened its base among non-Jews by relaxing some orthodox strictures, it nevertheless retained the parent religion’s fervor and paranoid intensity. The millenarian movement, which taught that the end of the world was at hand produced an anti-sensualist, anti-materialist bias. Remnants of Platonic Idealism and Greek Orphism further strengthened the Christian rejection of bodily enjoyment in order to qualify for salvation.

This is why the earthly joyousness and despair of the Dionysian experience is nowhere in evidence in this dour faith. Christ’s message was purifying as well as punitive, and it was preached in no little haste. As he was believe to have said, great evils would come to pass before his generation should perish. Even today, some two thousand years after their leader was proven so dreadfully wrong, one hears of fanatical bands who sell their property, resign their jobs, and retreat to a common home–all in the expectation of Jesus’ imminent return.

That he never came as predicted must have been an agonizing disappointment for the believer, who was forced to repeatedly reinterpret scripture so as to justify the delay of the Second Coming. But such a thin diet of fulfillment had a reverse effect than one might expect. Instead of causing its members to fall away, such disappointment only heightened expectation and caused a redoubling of purifying efforts. More and more, Christianity had to become the worship of an increasingly remote ideal, an increasingly delayed and heightened expectation.

In its most extreme forms it developed an obsession with the evils of the flesh and of life itself. Earthly existence–and the sins that rose naturally from the flesh–were to be suppressed. Present enjoyment was to be postponed for that celestial enjoyment which was sure to come. Given Yahweh’s capacity for destruction, there was simply no alternative.

The liabilities of such Essene/Christian asceticism were beautifully captured by William Cory in his Mimnerus in Church:

You promise heavens free from strife,

Pure truth, and perfect change of will;

But sweet, sweet is this human life,

So sweet, I fain would breathe it still:

Your chilly stars I can forego,

This warm kind world is all I know.

You say there is no substance here,

One great reality above:

Back from that void I shrink in fear,

And child-like hide myself in love:

Show me what angels feel. Till then,

I cling, a mere weak man, to men.

You bid me lift my mean desires

From faltering lips and fitful veins

To sexless souls, ideal quires,

Unwearied voices, wordless strains:

My mind with fonder welcome owns

One dear dead friend’s remembered tones.

Forsooth the present we must give

To that which cannot pass away;

All beauteous things for which we live

By laws of time and space decay.

But oh, the very reason why,

I clasp them, is because they die.

Lucifer, once Yahweh’s favorite Seraphim, was blamed for the sinful descent into sensuality. In subsequent artistic representation, he was sometimes given the horns and cloven hooves of the goat, an animal often associated with the pagan god Dionysus . These animal symbols were also associated with Pan, for whom the name of the Christian Hell, Pandemonium, derived. To follow this fallen “brother” of Christ in disrespect for the Father was Sin–which happens to be the name for the Akkadian goddess of the moon.

Prometheus, who like Lucifer rebelled against a paranoid and dangerous god, has enjoyed a much better press. Which is not mysterious at all.

But some gods had extended families. The dynasties of Greek gods are descended from Ouranos and Gaea. The first dynasty is the Titans, from whom Prometheus was descended. The succeeding and second divine dynasty is that of the Olympians. Its founder, Zeus, was the son of Cronus, the ruler of the Titans. But in a fit of paranoia, Cronus swallowed Zeus’s brothers and sisters to prevent them from staging a rebellion against him. He also tried to seize and and swallow Zeus, but could not locate him because he had been hidden away for safe keeping.

Eventually, Zeus matured and then exacted his revenge. The first task was to trick Cronus into swallowing a purgative that caused him to vomit up his swallowed children, still alive. Then, at war with his father, Zeus either castrated or imprisoned him. The accounts vary, with the usual imprecision of myth. And so the Titans had failed to solidify their original rebellion and were permanently dispossessed by the Olympians. Since Prometheus did not play an active role in the conflict, he was spared by Zeus.

Yet, Prometheus harbored resentment against Zeus for other reasons. Prometheus and his brother Epimetheus had created human kind. Unfortunately, Epimetheus (whose name means afterthought) had thoughtlessly gifted the animals with the highest attributes of animal powers: sight, locomotion, cunning, agility and strength. But he unfortunately had forgotten to save some of these attributes for naked, shivering, abject humans beings.

To compensate them, and to gift them with the power to rise up against Zeus, he decided to give them part of the sacred fire, which was jealously guarded by Zeus on Olympus. Zeus had strictly forbidden human access to this fire, which was a symbol of technology, progress and power.

So it is that Prometheus, like Satan, has defied the wishes of god. He captured an element of forbidden fire from the Olympian tripod, enclosed it in a fennel stalk, and brought it surreptitiously to earth to share and teach them how to use it. When this rebellious act is discovered, Zeus punishes Prometheus by chaining him to a rock in the Caucasus mountains–where he languished until Hercules freed him 30,000 years later.

As Prometheus says:

“New are the steersmen that rule Olympus; and new are the customs by which Zeus rules, customs that have no law to them, [and] what was great before he brings to nothingness.”

One encounters a similar motif in Genesis: a weakened humanity, a rebellious bringer of knowledge, an act of defiance which threatens god: Yahweh (aka Jehova).

“Now the serpent was more subtle than any other wild creature that the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, ‘Did God say, You shall not eat of any tree of the garden?’ And the woman said to the serpent, ‘We may eat of the fruit of the trees of the garden; but God said, You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, neither shall you touch it, lest you die.’ But the serpent said to the woman, ‘You will not die. For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God…'”

Yahweh corroborates this by remarking, after he has discovers the transgression:

“Behold, the man has become like one of Us (i.e. “god-like”) knowing good and evil; and now, lest he put forth his hand and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live forever’–therefore the Lord God sent him forth from the garden of Eden…”

The power of reason and individuation threatens divine hegemony, and also threatens to remove the Totem Father from his throne. A similar motif lies behind the story of the tower of Babel, the Mesopotamian ziggurat:

“And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the sons of men had built. And the Lord said, ‘Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; and nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and there confuse their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.'”

Why does Yahweh wear his crown so insecurely? Unless like Zeus, he has himself stolen heavenly power–perhaps from the Demiurge Ialdabaoth–and fears becoming a victim in the continuation of the cosmic struggle for independence: one phase of which has already been fought out in heaven between the divided forces of the Seraphim, the first of the “sons” of god.

The biblical story of the Nephilim is another symbol for the threat posed by the emergence of newer rivals:

“When men began to multiply on the face of the ground, and daughters were born to them, the sons of God (angels) saw that the daughters of men were fair; and they took to wife such as they chose.”

The offspring of this mating of angels and daughters of men was a race of giants, the Nephilim. The Book of Enoch describes the earthly arrival of the sons of god– his neocortical offspring– a host of some two hundred angels led by Samiazzaz. One of their number, Azazel, reportedly was responsible for teaching humanity the arts and sciences; giving, as did Prometheus, the power of “fire” or “intelligence” to a humanity in bondage.

Threatened by this new super-race, Yahweh ruminates on a solution.

“Then the Lord said, ‘My spirit shall not abide in man forever, for he is flesh, but his days shall be a hundred and twenty years.’ The Nephilim were on earth in those days, and also afterward, when the sons of God came in to the daughters of men, and they bore children to them. These were the mighty men of old, the men of renown. The Lord saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth…And the Lord was sorry that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart. So the Lord said, ‘I will blot out man whom I have created from the face of the ground, man and beast and creeping things and birds of the air, for I am sorry that I have made them.’”

What is the nature of this great evil that causes world wide disruption?

As Dodds has observed, in stories such as these it is clear that “the gods resent any success, any happiness, which might for a moment lift our mortality above its mortal status, and so encroach on their prerogative.”

Clearly, Satan is a Promethean type of rebel, and in seducing Eve into taking a bite of the apple from the Tree of Knowledge, gifts humanity with new powers. He lifts those disobedient children–the ancestors of all humans– from child-like submission into the painful realm of consciousness and independence:

“…Hence I will excite thir (sic) minds with more desire to know, and to reject envious commands, invented with design to keep them low whom Knowledge might exalt equal with Gods.”

About that, Satan did not lie: The bite of the fruit did indeed open their eyes. At a symbolic and familial level, we are witness to a transition that takes place in all normal families: the dependent and innocent child reaches adolescence, matures. Ultimately he or she “rebels” to take charge of his/her own life. Fortunately, most human parents understand this drive for independence as a natural–and desirable–transition. A coming of age.

Interestingly, the poet Milton was not insensitive to the Titanic grandeur of such deeds. His Paradise Lost makes Satan a tragic, heroic figure–though probably not deliberately. This is because Milton, despite his faith, was also an admirer of human intelligence. Pondering the irruption of this conflict in Milton’s text, Wm. Blake opined that the devout, orthodox Puritan was “of the devil’s party without knowing it.”

And like Prometheus, Christianity’s defeated Titanic rebel will also be chained to his punishment, only in this instance he will be bound to a lake of fire. Milton shows the congregation of fallen angels engaged in heated debate (no pun intended) about what action to take against the victorious Yahweh and his remaining angels. Consulting with his fallen companions, Mammon speculates on the options that the rebel angels now have before them:

“…Suppose he (God) should relent

And publish grace to all, on promise made

Of new subjection; with what eyes could we

Stand in his presence humble, and receive

Strict Laws impos’d, to celebrate his Throne

With warbl’d Hymns, and to his Godhead sing

Forc’t Halleluiahs; while he Lordly sits

Our envied Sovran, and his Altar breathes

Ambrosial Odors and Ambrosial Flowers,

Our servile offerings. This must be our task

In Heav’n, this our delight; how wearisome

eternity so spent in worship paid

to whom we hate.”

And in a remarkable anticipation of the terrible necessity of heroic choice, the devilish orator urges the fallen angels to establish their own world, “preferring hard liberty before the easy yoke of servile pomp.”

Why the Christians wouldn’t regard Satan as a defiant, Promethean hero who had saved humankind from dependency upon a temperamental father would have mystified more than a few Greeks.

Since Satan had already been punished–expelled from the cosmic primal horde but not killed– the only ones Yahweh had left to punish for this act of defiance were the mortals Adam and Eve. One way was to expel them from the garden, and thus distance them from the knowledge they desired. Other means were to compel them to bring forth their children in pain, to earn their bread by the sweat of their brow, and then to die–these ought to be enough to stop-up or displace their prying curiosity.

And yet ironically, Christianity itself was predicated on a mitigated kind of defiance, for its totem Jesus figure was a rebel who had also come to overturn the old law; who had come to set father against son; and who had come to pry his contemporaries loose from earthly allegiances to allegiances of the soul:

Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s;

Unto God what is God’s.

And:

“Do not think that I have come to send peace upon the earth; I have come to bring a sword, not peace. For I have come to set a man at variance with his father, and a daughter with her mother…He who loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me.”

Certainly, the religion that was founded by others in his name diminishes the worship of his father; for Christianity is actually a religion of the Son.

The later history of Christian antipathy toward the Jew seems an adequate enough testimonial to the existence of a long standing rivalry between the two faiths. And certainly the aspect of Christianity that emphasizes forgiveness must be predicated upon a maternal principle: that of the idealized Mother of pre-agricultural days; the Mother of tolerance and forgiveness described by Christopher Badcock (1980). As such, Christianity threatens the hegemony of the patriarch by raising the Mother to a new status of respectability; the which, should it occur in a household where the Father was absolute, would result in significant tension. Joseph, we may remember, was something of a stranger to Jesus, and according to the myth, was not credited with paternity.

Mary, on the other hand, must have enjoyed that special relationship that mothers often seem to enjoy with their eldest sons: sons who simultaneously venerate the mother, play the man for her, and who at the same time feel an ambivalent toward the maternal principle. Yet, the sexual polarities that play such a role in Judaism seem not to play a significant role in Jesus’ character. For though he rejects his earthly parents on consanguineous grounds, he nevertheless surrounds himself with women, and preaches a doctrine of nurturance and dependence that some would characterize as “anti-masculine” in the outmoded, and traditionally accepted sense. That his chief expositor, Paul, should be the misogynist that he was, remains one of the enduring ironies of intellectual history.

But to consider Christianity from another angle is to conclude that while the Father is displaced, he nevertheless lives on in the newer faith, albeit more remotely than before, and that the son is loyal to the father, not authentically rebellious: “I must be about my father’s business,” says the young Christ, and “No one can come to the father but by me.” The ambivalence expressed by Jesus throughout his mythic career is torturous indeed.

And yet, as the slain Son, Jesus also becomes the slain Totem–the instant leader of a new primal horde, as it were. To ask most Christians who “god” is, is to receive the answer “Jesus.” His supposed resurrection foiled those disbelievers who put him to death for blasphemy–the rebellious sons of this impromptu scenario–and after the fact of this triumph, who could now be castigated by the loyal sons who continued to worship the ever living and triumphant Christ.

Questions that derive from this complex of role reversal and ambivalence lead ever further into the labyrinth, and we need not pursue them (see Oedipus chapter). But with regard to the pagan tradition, it seems safe to say that Christ is not a humanist hero. Instead he is an anti-Prometheus. In the long run, it will not be his function to free human children from a willful father figure. Instead, as the shepherd, and as the unacknowledged hero of Judaic culture and of transference, his task will be to lead the sheep back to submission. Such loyalty, in Benjamin’s gender formulation (1988), may spring from “the unfulfilled longing for recognition from an early, idealized, but less authoritarian father.” This frustration of identificatory love, according to the author, prepares the way for surrender to the father-imago offered by the charismatic leader.

His mountain will not be Caucasus but Golgotha; his chains will be spikes and a crown of thorns, and instead of a vulture eating away at his liver, he will be stabbed in the side with a spear. This is heroism of a very high order, but one needs to be careful not to confuse it with Dionysiac, earthly heroism. Jesus plays the role of the non-combative masochist, rather than that of the liberator: He would have the earthly sons of the Father deny the titanic impulse to live an independent life without interference, without celestial coercion. He would have them lay down their arms. The virtues he teaches are humility and obedience, not pride and the defiance of celestial authority. Once esconced in heaven, however, the crucified man of the people will become both an administrator and a general of the armies of righteousness.

And so, through the actions of such resurrected deities the transference project solidified its hold. It flourished, and married itself to the other early religious traditions, even promising worldly success for those who surrendered.

Matter–mater– had given humanity mortal life, but this life was to become a despised thing: a prison, a vale of tears which held the soul in thrall.

Next: Kansas Forever: Finding Our Way Back Home Or: Back to Index