Dionysus: Stampeding the Gods

“I say, I say God is Dead!”

John Procter The Crucibl

We have previously examined several famous conflicts between gods: Set, who hacked his brother Osiris into pieces, Cronus, who castrated his father Ouranos, Zeus who fatally castrated and stabbed his father Cronus, the Titan Prometheus who threatens Zeus’s Olympian power, and the angel Lucifer who leads a deadly rebellion against tyrant Yahweh.

None of these stories is true, of course. The gods are the sock puppets of tyrants, mobsters and priests. They were created to control citizen behavior and create group/national cohesion. They escape scrutiny because, as As E.O. Wilson has said: “Human beings are absurdly easy to indoctrinate.” Very few among us actually questions the existence of gods.

The great tragedians have always understood this–but most of them have deliberately–or unconsciously–tried to obscure it from view.

These stories have prepare us to understand the significance of Dionysus, and of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. These are the ones who stampede the gods.

Dionysus, like Shesmu, Egyptian god of wine, like Set the brother of Osiris, like Shiva who dances the universe to smithereens, like the formidable Ahriman, and like Lucifer–is a god of chaos and disorder. As such, he represents the repressed, animal passion that all humans possess as part of their evolutionary endowment.

His trademarks: bloody ritual sacrifice, wild Corybantian dance, shrieked Ululatios, and the intocicating enthusiasm conferred by wine, the spilled blood of the grape. His animal representation, not unlike Lucifer’s, is often the horned goat, sometimes the bull.

He begins his life as Zagreus, prehistoric god of the hunt, and he precedes classic Greek culture by more than a thousand years. And when this alien first arrives in Greece, somewhere around 1400 BCE, he will ultimately challenges the Olympian/Apollonian basis of Greek religion itself.

Perhaps his greatest significance is that he is torn to pieces by the Titans, then rises from the dead. This resurrection motif derives from the Egyptian myth of Osiris, the god who symbolizes the journey of the seasons. Much later, of course, Christianity’s borrowed the idea of resurrection from the Egyptians as well.

The time is right for Zagreus/Dionysus, the hunter, to re-appear. For while the Olympian mythology is still dominant in Greek culture, its gods have become increasingly remote and abstract. Their cruel, vain, and pugnacious behavior still entertains; but they have tiresome. This is due to the gradual triumph of Apollonian values: balance, order, harmony, and reason’s triumph over animal passion. The now tedious Olympians memorialized by Homer and others have are no longer awesome. They have lost heir ability to inspire, and have gradually withdrawn from the world. The thrill is gone, and genuine religious enthusiasm begs for a revival.

We can better understand this development by reflecting a phenomenon from the 1960’s: the Beatles and their experimental foray into Hinduism and the teachings of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, among other gurus. America–and some of the west–received a flood of eastern gurus who inspired a new fervor in religious experience, and caused a surge of devoted followers in a number of States. Hare-Krishna was the new thing, and many youth were fully entranced. This is a modern example of what happened to the Greeks 2500 years ago–a time when new type of religious experiences was called for.

Zagreus/Dionysis was definitely exciting. The jarring, enthusiastic and chaotic qualities of Dionysus break with staid tradition. They are a forceful reminder of the varied routes by which the gods have entered the world. His joyous, ghastly rituals of sacrifice and his triumph over death–and the “drunken” enthusiasm that these rites engender–threatened to destabilize the maturing Olympian pantheon. If he cannot be successfully co-opted by the Olympians, he threatens to bring the Greeks face to face with elemental roots of primitive religion. And they don’t want to open that door.

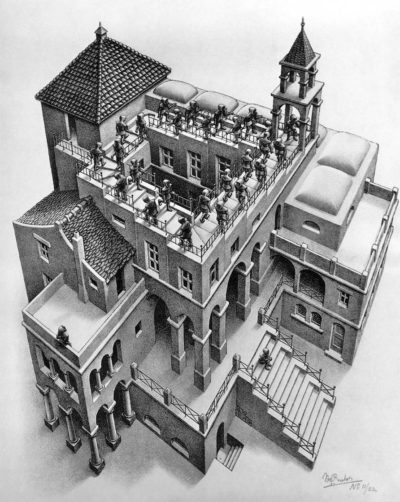

Dionysus was to be approached by descending Escher’s staircase rather than ascending. He urges spontaneity and life, not tame rationality, idealism or thoughtful devotion. In his worship ululations replace hymns, Corybantian dance replaced solemn processionals, shrieked ejaculations replace choral song, crazed Maenads replace priestesses and Oracles, drunkenness replaces meditation, and the earth, with all its vitality, danger, birth and death becomes something to rush toward rather than from.

His arrival, like Maharishi’s, is greeted with enthusiasm by a slowly growing number of influential people. He catches on. But the gate keepers of the old traditions are not charmed. They know a threat to their livelihood when they see one. They begin an earnest effort to co-opt this alien deity by inventing new stories of his origins and his life–ultimately co-opting the alien so as to make him one of their own. The rational precincts established by Apollo and enforced by Zeus must not be put at risk.

The resurrection that Dionysus promises centers on the awakening of passionate life, not Apollonian contemplation. Dionysus is the god “of renewal through the light from below, from the earth rather than from the heavens, and who signifies the necessity to find life and meaning in the ecstasies and terrors, in the beauties and agonies of this concrete world, not merely in the remote, abstract spirit realm as it is commonly understood” (Whitmont 1969). To make this clear: Dionusus resembles a fantastic Hippy on an LSD laced high.

The viscerality of Dionysian reincarnation becomes a Trojan horse that threatens to topple the very idea of a celestial hierarchy itself. His example teaches that passionate existence is the main goal of life. And even worse: that the gods are within us–not “out there.”

Dionysus comes from the depths of the psychic past to teach how and where the gods began. But who broke the locks to the door of the repressed unconscious? Who then aroused this beautiful monster from his slumbers and led him up and into the sunlit, Apollonian world that the reason had arranged into stale, coercive celestial hierarchies?

The very existence of Dionysus threaten to kill off the gods–unless they can kill him first. Which they ultimately do. His natural resurrection–the annual, repetitive cycling of the seasons– is refashioned by inserting Zeus, Hera, Persephone, Semele and others Olympians into his story line.

They invent new myths of his origins, and new family trees for his pedigree. They fabricate tales that Zeus is his his father and that Persephone is his mother. The strange plebeian is on his way to being adopted and sanitized by the patricians. They even turn him into something of a tyrant, as we shall see. But now that he is becoming one of them, he will be easier to manage and control. We own him. He is ours. We can even kill him if we have to.

That they try to do just that is reflected in yet another version of the myth. Hera, Zeus’ matronly superego, resents the beauty and insouciance of this illegitimate, all too attractive god. As the story would have it, his very existence is a constant reminder of her husband’s Zeus’s infidelity. An earthiness and vulgar exploitation of human females that he has been unable to repress…and which he always attempts to disguise. His preparation for rape often consists of disguise: he may be a swan, a bull, some other animal.

His wife Hera resents Dionysus–his existence is a reminder of her husbands randiness. To banish these thoughts, Hera reaches deep into the underworld to contact the enchained, ancient drivers of the human personality–the Titans. She orders them to tear Dionysus into pieces and devour him. Which they do.

The Titans eat all of Dionysus but the heart, which is snatched up by Athena and taken to Zeus for safekeeping–which now creates yet another new history for this inconvenient invader. Zeus plants the heart in his thigh, which later leads to the rebirth of Dionysus. In doing so, Greek mythologists have made a tremendous concession to an alien, Egyptian idea: the death and resurrection of a god. As I said previously, the story of Osiris will also be tacked tacked onto the Jesus story: the brutal death, the descent to the underworld, followed finally by an eye popping resurrection.

Yet another flood of myths confuse and embroider the story even more, attempting to lead the investigator away from the trail. The ruse is obvious. Some now say that Zeus plants the heart of Dionysus into the womb of Semele, a mortal maid. From her womb, the god is born again; and indeed, the name Dionysus itself later comes to mean “twice born.”

Still later versions present us with an intriguing lie, suggesting the impossible: stating yet again that Dionysus is the fruit of a sexual union between Zeus and Semele. But this timeand that the mortal maiden is tricked by Hera into self immolation. Hera dares Semele to ask Zeus to appear to her in all his thunderous glory. She makes the request. Because he previously promised her any wish she might make, he must reluctantly assents to her request, and when he does show himself, she is blasted into oblivion. The hidden moral of this revisionist story serves the forces of obscurantism. Deconstructed it means: to ask to really see the gods for the absurdities that they are is to ask for the destruction of culture as we know it.

With this ruse Hera consolidates her powers, and all that remains are the smouldering ruins of Semele’s house, the scene with which Euripides begins his play The Bacchae.

The infant demigod is rescued from the ash and flame and sent, some say, to live in the underworld with Persephone, beyond the reach of Hera’s revenge; or perhaps he lives far across the sea with the nymphs of Nyssa, another variant for the origin of his name. But wherever the myth says that he might be, the force that he represents lives on within the mind.

The First Communion

The newly transcendentalized worship of Dionysus now fulfills an ancient eastern resurrection formula. Its major elements are influenced by the Eleuinian Mysteries. This transformation, as well as the future triumph of a future Christianity, were bound to happen.

The Dionysian reformulation is also unique among vegetative/resurrecton religions for the clever means by which it resolves the ancient “proximity” question.

Osiris could promise resurrection as a product of specific ethical and ritual performance; giving his word that benefits would be conferred. But Dionysian ritual goes much further by returning the worshiper to totemic themes: the eating of the god. Hoc Est Corpus Meum says Jesus at the last supper. “This is my body, this is my blood.” This mantra is repeated each time a priest delivers holy communion into the gaping mouth of the celebrant. This phrase will also translated into “Hocue Pocus” by much later Protestants who mocked the idea of Holy Communion.

“Anyone acquainted with primitive mentality will expect that in many cases the cannibal feels that he is absorbing the manly virtue, the courage, and the energy of the slain warrior by eating him. He is transferring to himself the Mana of his enemy” (E. Sagan, 8).

This is the ultimate solution to the proximity question–the original solution described by Freud, as it turns out. To take the god into the self is to achieve a revolutionary closeness. But it is also to suggest that the god–dwells within. Not out “there.”

Prefiguring Jesus, Dionysus’ identification with blood becomes symbolized as wine. It marries the blood of the hunter’s killed beasts to its nearest agricultural analog, the blood of the crushed grape.

It was this doorway that the Maenads sought to open via their rituals. The doorway did not lead to heaven but instead led back to the self and to the pulsing heart of earth.

Leaving behind hearth, home, civic responsibility and all semblance of decorum , Greek matrons would slip out into the hills for their trance-like Bacchic revels. Here, according to legend, they would run semi-naked beneath the moonlight, snakes twined in their hair, waving their phallic, ivy decorated thyrsii like fiercesome wands. Their “enthusiasm” (enthusis: filled with the spirit) comes about as a direct result of drinking Dionysus’ blood: the wine.

In this way the most dangerous aspect of Dionysian belief, its joyous love of earth and of life on their own terms, is still kept alive–psychic embers which continue to smoulder as do the ruins of Semele’s Theban home. The argument that becoming, being and ending are beautiful transfers human allegiance from stars to the soil. It demonstrates that stars and soil are one–not metaphysically separate.

Euripides, in his last tragedy The Bacchae, shows us more of the Maenads:

“In a fit of sanctified frenzy…women young and old, and girls as yet unmarried. First, they let their hair fall down their shoulders and those whose fawnskins had come loose fastened them up, while others girdled theirs with snakes that licked their cheeks. Some cradled young gazelles or wild wolf cubs in their arms and fed them at their full-blown breasts that brimmed with milk…”

At the height of the ceremony the Maenads would take a goat, sacramentaly kill it, dismember it, and then eat its flesh and drink its blood. Euripides’ astonished herdsman continues to embellish the tale:

“You could see a woman sink her nails into a cow, with its udders full, and lift it, bellowing, high above her head. Others dragged young heifers, ripping them apart. Everywhere you looked, ribs and cloven hooves were flying through the air. And from the pine branches dangled lumps of flesh that dripped with blood.”

By the time of Eruipides, the mystery of life and death–of here and now– has been transformed by mythic invention into sympathetic magic. What Euripides chooses to remember, and insists upon, is that the most important lesson here is Chthonic affirmation. That he also reveals Dionysus as a self absorbed, amoral, cruel deity has to be both deliberate and fitting. His amoral and cruel behavior in the play–like the behavior of Apollo who sets up Oedipus for destruction, warns us away from the danger of aligning ourselves with any deity, Dionysus included.

This simple beginning, as we have seen, had become over determined and gratuitously complicated. The battle waged at the heart of the tragic myth centers around the universal struggle within the self– the explosion of the inner body Daimon against the culturgenic repression of earthly enjoyment in service of culture’s desire to control.

The theological complexities that infest later tragedy require the hero to play a number of roles. The hero is the intermediary, the tester, the shaman, the priest, the savior-guide and the victim all at once. Like Jesus, like John Procter, the hero finally engineers his own spectacular failure. Mission accomplished: Success.

On a manifest level, tragic rituals constitute both a promise and a warning: it is dangerous to choose religious intoxication over acceptance of life, and its terrifying duopoly of beginning and ending. Surrender to the gods brings disillusion and loss. Hamar-tia. Which leads to a newly understood level of success.

His play The Bacchae ends in this renunciation of the gods. It awakens the dancer to a mortal existence un-redeemed by mitigating rituals of sacrifice and religious devotion. Awakening from her murderous frenzy, Agave realizes that under the guidance of Dionysus she has decapitated her son Pentheus. Closed minded Pensheus was also hypnotized by Dionysus to position himself for slaughter. He was gently dressed by Dionusus as a woman so as to spy on the women as they enjoy their Dionysian orgy. Their vision distorted ably by Dionysus, the women assume that Pentheus is a wild animal who has stupidly come to be sacrificed.

After she discovers that she has murdered her own son, Agave returns to her senses. She sees what she has accomplished under his dangerous spell. She scolds Dionysus and declares:

The gods should be above the passions of mere men!

Dionysus has fulfilled his mission. He has taught everyone a lesson: surrender to the gods brings madness, pain, and illusory joy.

Arthur Miller’s THE CRUCIBLE

To deconstruct manifest content is to reveal deeper themes. Their existence is confirmed by the fact that the deep structure of the tragic form insists on making itself known time and time again. Modern tragic heroes, such as John Procter in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, will embody both the yearning of the life force, as well as the existential, skeptical principle which the Agavid dance produces the morning after. As such, and at a latent level–and now we remember the symbolic function of Set, Shesmu and Zagreus–the hero represents that part of the human mind which can see into the heart of ceremonial magic, recognizing it as reaction-formation that leads from remorse into a stunning revelation. In wishing so powerfully, the hero–and the audience–learn not to wish.

Let us consider how Arthur Miller borrows these complex, subversive symbols of psychic division, and mirrors the tells us again about the entry of Dionysus into a yearning, overly constricted Puritanical world.

Procter, entirely too independent and passionate to be contained for long in the ideologically narrow Puritan village of Salem, seems to be a repository of the wild spontaneity and cantankerousness of Dionysus. He is no respecter of Puritan traditions–all of which declare war on the impulsive, sensual, Dionysiac side of his own nature.

Procter’s smouldering resentment manifests itself as poor attendance at Sabbath meeting, as well as in his addiction to truth telling. Both of these characteristics set him up as the shadow-enemy of conformist society, and as such demand his sacrifice. He must become the recipient of Hera’s revenge, and his nature and the threat his nature implies must be contained.

Procter’s sin of lechery offends Hera, as much as does the existence of the illegitimate Dionysus. The myth insists that he must pay the same price as does the god. Like Orpheus, Procter will be torn apart by his own “Maenads,” the crazed girls of the community who are led by a new Agave, Abigail Williams.

Brought into the Procter household to assist his wife after a difficult pregnancy, Abigail will find herself drawn to John, and the two will fall victim to a lawless, Dionysian passion. This affair brings new consciousness to Abigail, and raises her from the suffocating existence free spirits must feel when surrounded by restriction. Attacking his reluctantly dutiful attempts to break it off, she tells him he still must love her, and that she has reason yet to wait for him to be hers:

“I know how you clutched my back behind your house and sweated like a stallion whenever I come near!…I look for John Procter that took me from my sleep and put knowledge in my heart! I never knew what pretense Salem was, I never knew the lying lessons I was taught by all these christian women and their covenanted men! And now you bid me tear the light out of my eyes? I will not, I cannot!”

Association with this Dionysus has exposed the “lie” of culture, and Abigail’s repressed intensity sublimates and displaces into the protective lying engendered by the witch trials. These are society’s attempt, on behalf of the new gods, to detect and destroy the alien agent who threatens the collapse of the mind’s carefully erected hierarchies. As in The Bacchae, the instrument of destruction manifests itself as feverish madness.

Abigail’s hunger for a fuller life is a hunger that culture cannot sanction. Thwarted and driven by a hysterical fear, she succumbs to a form of aggressor identification, and now uses the law and the terrible inquisitorial procedures to strike at life. The arrest of Procter’s wife imitates the death and descent of Eurydice, and so Procter must assume the role of Orpheus–a later variant of Dionysus–in order to become the savior who unlocks the gates of the underworld.

But the gates that Procter really unlocks are those of the subconscious, and like Golding’s Simon, Procter will be driven into a fatal, heretical corner to be killed. But not before he can communicate his terrible discovery to a horrified world:

“I say, I say, God is dead! A fire, a fire is burning! I hear the boot of Lucifer, I see his filthy face; and it is my face, and yours Danforth…and the face of all those who quail… to bring men out of ignorance!”

This is the discovery which the critical intelligence has insisted upon all along: the myths are lies, and adherence to them prevents humanity from moving from an imaginary “more” to a more realistic, and more satisfying “less.”

Like Persephone and Dionysus both, Procter is also the apostle of spring and rebirth– “it’s warm as blood beneath the clods” — only this rebirth is symbolic of a threatened emancipation of the self from the snarly mesh work of the mind’s delusional quests. Knowledge is life, and when the hero is imprisoned, a wintry ruin settles upon Salem.

Of course the play is about the nature of evil, but in this play the source of evil lies in humanity’s obedience and submission to a hierarchy that it has invented and magnifies unnecessarily guilt and repression–symbolized as the attacks of both Sphinx and plague in Oedipus Rex, or the court and the slaughter in Salem.

The gods, of course, have sentenced all mortals to die, and so Procter’s lechery is a most natural sin for the living, representing as it does the only plausible assault that mortals can make on the problem of finitude. This is humanity’s only hope, but the paradox is that birth is also a guarantee that the power of death– so ably wielded by Danforth, the deputy governor of the underworld–will continue unabated. Procter’s death will appease the court for a time; but no sacrifice will ever satisfy death’s hunger.

The ostensible purpose of such rites of sacrifice and propitiation is to legitimize the imaginary division that exists between earth and stars, and to portray humanity’s ancient attempt to bridge the gap through primitive ritual and sympathetic magic. But all such stories serve to forcefully remind their audiences of the real human dilemma: psychic division and conflict generates both the problem and its solution. For though the conclusion of both Oedipus and the Miller play end with some hint of surrender to deity, the fact remains that it is the conception of deity itself that is the cause of the trouble. Should the gods of the plays vanish–cease to act and cease to be accounted real–the tragic events would not unfold as they do. The gods are agents and causes–the Oedipal prophecy truly belongs to Apollo, not to its human initiator, Pelops.

Why tragedy, therefore? Though it derives from religious roots as we have seen, its ultimate aim is to discredit human proclivity for error. Works like these can cause the critical faculty within the spectator to turn away in horror and disgust at the folly of the pattern. Like pantomimic dumb-shows begging for interpretation–the Oedipus for example–they constitute a secret revolutions against the very processes and themes that the works ostensibly present as inviolable truths.

What we now face is the fantastic possibility that the rites of communion and sacrifice themselves have a latent function which is nothing less than to undermine the very foundations upon which they are performed. Seen in this light, they become false propitiations, directed at nonexistent temples inhabited by non-existent gods. The miracle is that the recipient of this chaos of traditions, Christianity, has survived the centuries more or less intact without collapsing under the stresses that must necessarily arise from internal paradoxes such as these.

Much of this phenomenon can be credited to the inventiveness of the mind and its ability to forge synthetic wholes from disparate, contradictory elements–intellectual bridge-building, of which the Aquinian reconciliation, is only one phase.

As we have seen, when goats and blood became unfashionable, the new generations of Dionysian Maenads and male fellow-travelers substituted bread and wine as symbols for the body and blood of the god : A striking early precursor of the Christian form of communion where the priest, breaking the bread over the wine, pronounces the magic words–“Hoc est corpus meum” –this is my body. The bread was then broken, as was the body by the ordeal of the crucifixion.

Next: Prometheus, Satan, Jesus Or: Back to Index