Post Modern Oedipus:

Sophoclean Masquerade…Or Farce?

As gods evolved from their animistic origins, their powers simultaneously increased. This transformation created deities who had human faces, human behaviors, human emotions and human appetites. They were created in man’s image and likeness–not the other way around. They began as little more than the hypertrophied parents of every child’s earliest world. Like parents, they could protect, they could help, they could command, punish and reward. Some of them ultimately came to ruled earth, the stars, and the future.

And yet, no matter how powerful the gods became–and no matter how many benefits worshipers were promised by their priests–misfortune continued to occur as frequently as ever. Prayer, sacrifice, and ritual did not guarantee a trouble free life.

Often the gods could behave like very bad grownups: not helpful, often jealous, protective of their superior status, easily threatened, self absorbed or indifferent. Such misbehavior undermined the quid pro quo of prayer and sacrifice, and justified this failure has always been faith’s greatest challenge. Almost immediately, it became clear to the myth makers that the gods themselves would need triage, some sort of rescue.

The earliest effort to rescue the gods occurred in Sumeria during the second millennium B.C.E. At a loss to explain why one city received good fortune and another didn’t– especially when the disadvantaged city performed just as many sacrifices as the favored one –Sumerian priests invented a council of the gods which met once a year to apportion justice.

It was at this council– the Anunnaki– that a god of the city of Lagash might be outvoted in favor of the god of Uruk–a gimmick that insulated priests of Lagash from an accusation that they failed to deliver for their dependents. There was a process that governed human events after all. Lagash just didn’t get the good breast this time around. But it was neither the god’s nor the priest’s fault.

A much later Lucretius, expositor of Epicureanism, was not deceived:

The nature of things has by no means been made for us by a divine power: so great are the defects with which it (the world) is encumbered.

We skate close to the Post Modern with remarks like these. Lucretius understood that tragic events and varieties of injustice could not forever be excused by attributing them to a benevolent god who was either outvoted, or who had some mysterious plan.

No one has better captured the frustration caused by doctrinal contradiction better than Mark Twain. The conclusion of his Mysterious Stranger describes the absurdity of divine “goodness” this way:

According to Twain, we foolishly continue to believe, he said, in a God who:

“Could (have made) good children as easily as bad, yet preferred to make bad ones;

who could have made every one of them happy, yet never made a single, happy one;

who made them prize their bitter life, yet stingily cut it short;

who gave his angels eternal happiness unearned, yet required his other children to earn it;

who gave his angels painless lives, yet cursed his other children with biting miseries and maladies of mind and body;

who mouths justice and invented hell–mouths mercy and invented hell–

mouths Golden rules, and forgiveness multiplied seventy times seven, and invented hell;

who mouths morals to other people and has none himself; who frowns upon crimes, yet commits them all;

who created man without invitation, then tries to shuffle the responsibility for man’s acts upon man,

instead of honorably placing it where it belongs, upon himself;

and finally, with altogether divine obtuseness, invites this poor, abused slave to worship him!” (Mark Twain)

Such revolutionary points of view have been successfully suppressed for thousands of years, until Oedipus Rex prepares the way for public rejection of the gods. Before we attempt to understand its remarkable implications, we must briefly compare Greek religious belief with christian belief today. Such comparison makes it all the more remarkable that religious skepticism would arise in classic Greek times.

For while early Greek and christian religions share superficial similarities, they are completely different at the core. Thanks to its laxity, Greek religion provided little impetus for rejection of the gods. Christianity, because it threatened eternal damnation for sin, and because of burdensome guilt it strongly engendered, invited resistance and rebellion much more readily.

Superficial similarities between them did exist. The original christian church is the Catholic, and several of its most important doctrines were borrowed from previous pagan traditions. This included a belief that there was a god who fathers a son born of a human female; that such a birth was a virgin birth; that this divine son is murdered, descends to the underworld, and then returns to life, and a belief that this son of god sits in judgment of all humans at the end of time. We cannot forget that according to Calvin, the number of those saved at the end of time would be somewhat below 200,000 of the billions who have ever lived.

Other harmless pagan borrowings would include the belief that a few, special humans could be rewarded with eternal life in the celestial hierarchy. Catholic adoption of this concept includes the Canonization of saints, and especially the doctrine of Mariolotry–the deification of a human female. Mary is the virgin “Mother of (Jesus) God.” Instead of dying, as all mortals ultimately do, she ascends to heaven where she continues to play a vital role as the great intercessor. Despite the fact that she was a human, she enjoys the status and powers of a pagan goddess. Add to this polytheistic smorgasbord the nine orders of angels: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Principalities, Virtues, Powers, Dominations, Archangels and Angels. Finally add the Trinity of the Father, Son, and the Holy Ghost. At this point it becomes clear that Christianity did not replace paganism, but fulfilled it.

These recycled inheritances did not diminish the need for doctrinal triage on an Olympian scale. Unwittingly, they increased it.

This becomes clear when we list a few of the hastily created attributes that christian theologians added to Yahweh’s burgeoning quiver of capabilities. These additions raised him from his origins as a humble, easily angered god of herders into a truly imposing figure: the creator of the universe and all its enormous variety of creatures.

To list a few specific additions to his quiver of attributes is daunting:

Incomprehensibility, Incorporality, Infinity, Jealousy, Mercy, Omnibenevolence, Omnipotence, Omnipresence, Omnisapience, Oneness, Patience, Righteousness, Sovereignty, Transcendence, Wrathfulness, Wisdom, Infinitude, Holiness, the Trinity, Faithfulness, Self-Existence, Self-Sufficiency, Justice, Immutability, Mercy, Eternality, Goodness, Graciousness and more.

The purpose of inventions like these was strategic. They were designed obscure divine failure by enshrouding the deity in an indecipherable complexity and inscrutability. In the face of such complexity, it was made impossible for anyone to understand, let alone criticize, the god. Yes, god works in mysterious ways.

We all know that anyone who lies eventually gets tangled up in the details of the lie. These ad-hoc details are concocted on the spot, are hard to remember, even harder to keep straight. Sooner or later the the contradictions become visible to others. Finally, the liar becomes trapped in his own exculpatory scheme, snared by an unfortunate invention of his own devising.

As we shall see, ill advised additions to Yahweh’s repertoire of attributes ultimately entrapped the god himself. Soon enough, he will become a Houdini, floundering in doctrinal chains at the bottom of a swiftly flowing river: A pitiful god struggling to free himself from the mesh-work that theologians had crafted in order to save him from scrutiny.

A classic starting point of this conflicted dilemma are the attributes of Omniscience , Omnipotence and Perfection.

An Omnipotent god is one who has the power to do everything–who can do anything he desires.

An Omniscient god can foresee the future–correctly. The future that he foresees must occur exactly as foreseen because he cannot be mistaken.

A Perfect god is one who can never change, never say “oops” as he reflects upon previous actions.

This is because Perfection is defined as the condition to which there can be no improvement added.

Perfection is singular, not plural. Any change made to Perfection must, by definition, represent a state less than perfect: a diminution of the original. A perfect god cannot change his goals, not even change his location or supposed position should he ever desire to. He can have no need to move, no need to change. It would be absurd for him to have any need whatsoever. Similarly, he cannot even desire a thing because as a perfect being, he already has has everything he needs. Ultimately, his Perfection cancels his Omniscience, and renders him immobile: frozen, unchangeable and everlasting. A Perfect god becomes as impotent as a statue of the Buddha. Suffice it to say, the unsophisticated Greek religion never faced this problem.

It gets worse. He is condemned to see a future that he now cannot alter. He cannot alter it because he has already seen it occur before it actually happens. It must therefore happen exactly as he foresees it. He cannot change it because to do so, an “oops” would indicate that he is flawed, has somehow made a mistake.

As a prisoner of his own omniscient powers, consider what horrible scenes he is compelled to witness as they unfold in real time: the enslavement of different peoples through the centuries, famine, plague, ubiquitous cruelty and injustice, the crushing effects of unrestrained capitalism, and the persistence of greed and imperialist depredation. He also foresees the abuse of indigenous children committed by catholic employees of Canadian and American schools. He is compelled to witness–in detail–the ubiquitous, well documented child abuse committed by the rest of his clergy around the world.

Faith destroying questions arise from this predicament: Does god approve of the mess his world has become? Why doesn’t he correct the evils running free in his creation? Is this the best he can come up with? Why does he permit the suffering of innocents if he is truly loving and omnipotent?

As Archibald McLeash summarized this dilemma in JB:

If God is God He is not Good;

If God is Good He is not God.

We can cannot delight in the imperfections of the world that god has apparently allowed? But we can feel some degree of schadenfreude for poor Yahweh’s dilemma.

All the implications of this dilemma converge as we examine biblical, pre-scientific ideas about human origins: the Story of the Garden of Eden and its punitive, sorrowful ending.

Were Adam and Eve set up? Did the god of the Old Testament create the garden, knowing it would never be theirs? Did he plant and nurture the tree of knowledge, knowing that its forbidden fruit would be eaten? Did He create the tempter Lucifer, his “morning star,” knowing that he would lead a host of rebellious Seraphim into damnation? And did He then place humanity’s supposed first parents into this tantalizing paradise, but only after endowing them with both a fatal curiosity and a weakness of will, so that when they fell–as He knew they would, as He knew they had to– he could then have the “satisfaction” of damning them and the vast majority of their descendants to the eternal torments of Hell?

WHY THE SKEPTICISM OF THE OEDIPUS IS UTTERLY REMARKABLE:

The early Greeks had none of these contradictions to face. Remember that remarkable fact. And what a difference this makes in terms of feeling comfortable with, or unconscious resistant to, one’s religion.

Here’s why: The Greeks knew that their gods should not be crossed or challenged. But the Olympians were not expected to be good nor consistently fair. None of them claimed to be perfect–not even “eternal.” Even Zeus knows that he will ultimately die.

As the earthy myths show, collective Olympian behavior could often be characterized as vain, petulant, grasping, pugnacious, sexually promiscuous, self aggrandizing and jealous. Yes, very human in other words. Yahweh shares several of these traits as we know. But these similarities do not derive from similarities in the religions, but rather from the fact that all deities have been created by humans in their own likeness. They are all of us, writ large.

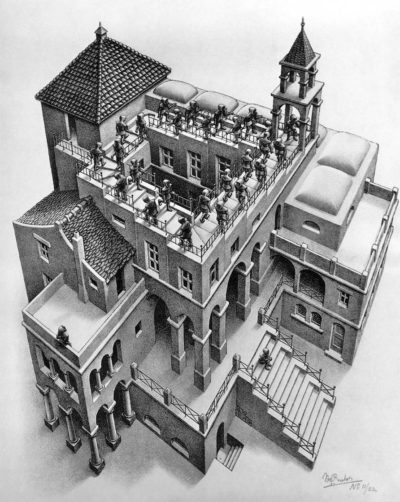

The earliest forms of Greek religion were as simplistic as Model T’s. Superstition abounded, the empire of the unknown was enormous. There was no specific dogma to believe or adhere to. No Baltimore catechism to memorize. No confession. No burnings at the stake for disbelief. No yearning for forgiveness. No mind wracking preoccupation with guilt and the need for life long atonement. No mortal sins that led to damnation. No heaven. And no Hell as depicted here by Brueghel.

I said there was no greek “hell.” Yes, there were myths which describe the torments of a few offenders: Sisyphus pushing stones uphill, Tantalus unable to eat or drink, Ixion’s wheel. But these creations were post hoc literary embellishments, products of generations of creative writers and story-teller. They added to and embellished these novelties to what had always been an organic, straightforward religion. But they were not articles of faith or belief.

All religions, as they grow, accumulate myths that are dreamed up along the way. This is a natural process, and it occurred in Christianity as well. The gospels, for example. They were written at least 80-100 or more years after the the supposed death of Jesus. The authors, some of whom use made up identities, had never met Jesus. Neither had they met anyone who had met Jesus. By the time they write their stories, all they have is folklore to guide them. Jesus left no words. The Romans, meticulous record keepers, had no record of the supposed trial, nor of the crucifixion. Romans did write about their troubles with the Jews, and trouble with a little band that followed a deceased rabbi they named Cristus. Whether Cristus was real, or not, was ever reported.

When it comes to clergy: the Greeks did have temple priests, but these were administrative positions, not especially “religious.” The Roman scholar Plutarch served for a time as head temple priest at Delphi–something like the Greek National Cathedral. Similarly, Julius Caesar became Pontifex Maximus of Rome’s state cult in 63 BCE. He was not selected for his special “faith” or for his spirituality. His appointment was a political gift, a sinecure, a reward for service to empire. No one thought of him as the living, Papal, earthly representative of god, ably supported by a dedicated religious hierarchy. Instead, Caesar was known to be a clever, life long power seeker, and an enormously successful military commander. Both a highly capable and a brutal man.

The early Greeks had no hell to be threatened with. At death, a Greek descended to the underworld, lived there for a generation or two in the chill darkness, and then vanished about the same time everyone on earth–who remembered him– had died.

Punishments did exist at the city, state and national level. Punishments for egregious or dangerous behavior. But never for dis-belief. And most important, the usual categories of sin that most humans naturally indulged in could be enjoyed as part of life. They did not lead to damnation. This is because Greek religious practice, religious life, were not cosmic tests of human purity or faithfulness to doctrine. Guilt was not inherited and required no life long expiation.

The Greek gods can help you, or they can get in your way. The practical thing to do would be to make personal or material offerings to them. Talk privately to the god and show your respect. Religious worship is contractual, not spiritual.

Of special interest: The early Greeks had no Heaven such as that envisioned in Christianity. Zeus was powerful, but not absolutely like Yahweh. Poor Zeus lived on a literal mountain–Mount Olympus–not in the empyrean. The Greek Elysium (heaven) was not an article of faith. It was yet another post archaic creation, a literary embellishment most likely influenced by eastern mythologies: stories that began seeping into Greece near the end of the archaic period.

So it is that the idea of overthrowing the gods–something Mark Twain would have favored–was not popular in the Archaic period, not a fast growing meme. There just wasn’t much motivation to do it. Until the time of Oedipus.

Consider Oedipus:

If Laius, king of Thebes, marries and has a son, that son will grow up to kill his father and marry his mother. Apollo’s Oracle alone has declared this prophecy on several occasions.

The causes of the curse are both murky and unimportant–especially unimportant to Sophocles. His purpose is not to trace its history or to examine any justifications for it. What interests Sophocles is that it exists, its ownership and execution have been assumed by Apollo, and what remains is to see whether a god can prevail over a man.

Laius and Jocasta do indeed have a son: Oedipus.

We now prepare to witness how the sins of the father will be visited upon the innocent son.

Fearing that the curse might come true, Laius and Jocasta cruelly pin the infant’s feet together and give him to a servant to be exposed on the slopes of Mt. Cithaeron. If the infant dies as planned, he obviously cannot grow up to fulfill the prophecy. They will avoid fate.

But the servant does not fulfill the filicidal command. Instead, he compassionately gives the infant to a shepherd passing through on his way to Corinth. There the infant will be adopted by that city’s king and queen, and will be raised up in ignorance of his Theban origins. As far as Oedipus can possibly know, he is a Corinthian and his biological parents are Polybus and Merope.

From this point on, the fate of Oedipus and his biological parents is a foregone conclusion, ironically precipitated by both the shepherd’s and later Oedipus’ efforts to do the right thing. And though the hero will make a number of choices in his tragic career, all of them will have been foreseen–and therefore foreordained–by Apollo.

When the young Oedipus accidentally overhears the prophecy and leaves Corinth to avoid killing his (unbeknownst foster) father and then marrying his (unbeknownst foster) mother;

When he meets and kills the elderly, pugnacious stranger (his biological father) at the narrow mountain pass;

When he arrives at Thebes as a stranger and uses his unaided wits to answer the baffling riddle of the Sphinx, thus ending the plague that Apollo has purposely visited upon its citizenry;

When he is embraced by a desperate, leaderless Thebes as a savior and is pushed into marrying the newly widowed queen without knowing that she is his real mother;

And when he insists on continuing with the investigation of the causes of a still newer plague sent to Thebes by Apollo as punishment for its harboring a mysterious regicidal outlaw–himself:

What purpose is served by this incredible admixture of evil intent and impenetrably false appearances?

The events of the play compel us to ask: “Is Oedipus ever really free?”

Determined to “justify the ways of God to Man,” standard criticism declares that Oedipus’ character flaws are responsible for his destruction. Critics who pursue this line of thought resuscitate the doctrine: Omne bonum a Deo; Omne malum ab homine. In other words, all that is good comes from god; all evil comes from man. Oedipus the scapegoat will suffer in order to absolve Apollo and the gods for extant evil: Whatever torment awaits Oedipus will be the just consequences of his poor choices and behavior.

Some of his flaws are imagined to be:

That Oedipus it too proud;

That he does not know his place in the great scheme of things–does not even know who he is;

That Oedipus believes he sees clearly when he cannot, whereas the blind prophet Teiresias can in fact see.

And the moral with regard to Teiresias? Deconstructed it would be this:

Fictional, blind prophets can see and understand the mysterious ways of fictional, made-up gods.

Those who are not superstitious– not-blind–cannot see or understand the ways of these gods.

The Blind Prophet alone is entitled to lead those with sight, and his blindness must remain unchallenged if humanity is to persevere.

If these are the lessons of the play then it should be clear why it exists, as well as whose interests it serves.

Simply put, as a reality-tester, as an accurate map that describes a real territory that humans must contend with, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex has little value.

Its apparent goal is to re-establish the power of the dying Olympian gods. It may also be attempting to attribute the disaster of the current Peloponnesian war to specific behaviors exemplified by Oedipus.

Or is that its aim?

If Sophocles’ goal is merely propagandistic, then we must regard the drama and its dramatic personae as distortions created not for truth, but for political purposes. It is not an authentic investigation, but something more like a screed. As such, there would be little sense in parsing out the lessons of the action–because these will serve what the author’s intention requires.

Oedipus’ position as king and as savior of Thebes obliges him to lead the investigation into the plague. A clear cause and effect must be found. Since the audience already knows the cause, what then is the purpose of the dramatic action? The answer must be: A trap has been set, and a wind up toy will be compelled to move toward personal and political annihilation.

The reason for the plague is soon revealed by the Oracle: there is a pollution in Thebes–a crime of both regicide and incest. These crimes have been committed by one mysterious, unnamed individual who lives within Thebes. Who can this be?

The sightless priest Teiresias is now brought in to provide insight.

Though he is regarded by Thebans as the wisest man on earth, he responds to Oedipus’ initial queries with stubborn, riddling resistance–followed at last by a blurted allegation: Oedipus, the savior of Thebes, is himself the polluter, the cause of the plague.

Is he? Did he set out from Corinth to kill his father and marry his mother? Since he was abandoned, he can have no accurate idea of his actual parents, and therefore must considers the Corinthians Polybus and Merope to be his actual parents. He has left Corinth in order to avoid the prophecy that has accidentally overheard in the Corinthian royal court.

Provoked, Oedipus rounds on Teiresias the tells him what he really thinks of curses, divination and the gods:

“What was your vaunted sercraft ever worth?

And where were you, when the Dog-faced Witch [Sphinx] was here?

Had you any word of deliverance then for our people?

There was a riddle too deep for common wits...Until I came–I, ignorant Oedipus, came–

And stopped the riddler’s mouth, guessing the truth-deprived By mother-wit, not bird lore.”

Which happens to be entirely true.

Moments later Jocasta will make a similar remark:

“No man possesses the secret of divination…After this, I would not cross the street for any of it.”

The comic book battle is now joined.

The Role of the Chorus

The chorus of Greek tragedy possesses a special, almost supernatural power. It often acts as the collective voice of tradition as they interpret (and color) the evolving action. It’s a taste of the real world of current opinion.

Throughout the play, the chorus declares that it is man’s place to accept the controlling power of the gods, to be subservient to them, and to allow their hegemony to go unchallenged. Because they speak directly to the audience, they are the barometer that reflects the concerns of the contemporary Athenian audience.

On the one hand the chorus gives Oedipus credit for single-handedly saving Thebes. Then it simultaneously undermines that praise by warning Oedipus to remember his place:

“If we come to you now, sir, as your suppliants…I and these children, it is not as holding you the equal of gods, but as the first of men…or in the encounters of man with more than man. Your diligence saved us once; let it not be said that under your rule we were raised up only to fall. Save, save our city, and keep her safe forever!”

The question we must that remains open because undeclared is: Saved from what, exactly?

III

For some time now, and especially during this century, the allure of the traditional Olympian gods has been diminishing.

The assaults of scientific inquiry and a rising tide of skepticism regarding the gods and their traditional powers is partially to blame. It is evident to some that an essential balance, an appropriate proportionality, has been lost–as manifested by the hubris and imperial greed that have fueled the catastrophe of the elective Peloponnesian War. Athenian citizens, however, have supported conquest and empire ever since the sea battle at Salamis. The Athenian empire and its lust for hegemony and war have been joint projects of its leaders and citizens combined. Modern American wars are no different.

Apparently what is now required is a monumental public drama that attacks these developments and simultaneously calls for a return to the old ways.

The war was instigated by Athens, and after twenty-seven years resulted in the well-deserved military failure of the Athenian empire. Its own Viet Nam, its own Iraq, its own Afghanistan so to speak. The war began in 431. In 430 a devastating plague broke out in Athens. Within one year over 30,000 citizens perished, including their leader Pericles.

During this period, Sophocles was a member of Pericles’ inner circle, and his Oedipus Rex was first performed in BCE 429 (two years after the plague of 431-430 BCE). Clearly the chorus of Oedipus now describes the actual conditions within contemporary Athens:

“You too have seen our city’s affliction, caught in a tide of death from which there is no escaping. Death in the fruitful flowering of her soil. Death in the pastures; death in the womb of woman; and pestilence, a fiery demon gripping the city, stripping the house of Cadmus, to fatten hell with profusion of lamentation.”

The nascent post modern skepticism of the Periclean circle, which included skeptics and atheists such as Anaxagoras, Protagoras, Aspasia, and Phidias, was famously upsetting to average Athenians. Its members were better educated than the commoners, and their temperament tended toward rationalism and agnosticism, not piety.

A younger member of this circle, Alcibiades, was a magnetic, amoral carouser–a favorite of the wine loving and truly gifted Socrates. Alcibiades was credited with the a prankish destruction of the votive Hermes that fronted many homes on the eve a disastrous invading Sicily in 415. Another close associate within the Periclean orbit–Sophocles himself–enjoyed the company and access to power until chaos ensued.

A revealing example of this new, threatening skeptical attitude comes from the career of Pericles itself, as described by Thucydides. Again, this skepticism is not about escaping from religious tyranny–as it was to become during christianity’s glory days–but was entirely about thinking clearly.

“To inflict some annoyance upon the enemy, [Pericles] manned a hundred and fifty ships of war, and, after embarking many brave hoplites and horsemen, was on the point of putting out to sea, affording great hope to the citizens, and no less fear to the enemy in consequence of so great a force. But when the ships were already manned, and Pericles had gone aboard his own trireme, it chanced that the sun was eclipsed and darkness came on, and all were thoroughly frightened, looking upon it as a great portent.

Accordingly, seeing that his steersman was timorous and utterly perplexed, [Pericles] held up his cloak before the man’s eyes, and, thus covering them, asked him if he thought anything dreadful or portentous of anything dreadful. ‘No,’ said the steersman. ‘How then,’ said Pericles, ‘is yonder event different from this, except that it is something rather larger than my cloak which has caused the obscurity?'”

In this example, Pericles demonstrates to superstitious sailors that mysterious phenomena are amenable to rational explanation. Ignorance mistakenly identifies these events as coming from the gods.

“Man is the measure of all things,” said the sophist Protagoras, an associate of Pericles, “both what they are, that they are; and what they are not, that they are not.” Translation: Man proposes, and man now disposes as well. In the words of the Athenian invaders of Melos, as reported by Thucydides,”might makes right.” This confirmation of the Protagorean idea that humans are the judge of morality can be re-stated this way: Because the gods have no morality themselves, we can legitimately leave the gods out when it comes to questions about what is right, what is wrong.

This intellectual and skeptical trend is both electrifying and frightening. We get a sense of the common Athenian’s resistance to these ideas when Sophocles’ chorus prays for a return to the old ways, the old beliefs:

“I only ask to live, with pure faith keeping in word and deed that Law which leaps the sky, made of no mortal mould, undimmed, unsleeping, whose living godhead does not age or die”

At the conclusion of this desperate, yearning speech, a skeptical Oedipus rejects their request that he rely solely upon the gods:

“You have prayed; and your prayers shall be answered with help and releases. If you will obey me.”

We are presented with two alternatives: ask the invisible and perhaps non-existent gods to cure the plague, or rely upon human intelligence to solve it. Which shall the citizens choose? Today we understand that science is the basis of the only truths we can know (Anthony Fauci’s dismal performance not withstanding). We also understand that religion has misled humans for millennia. It may be comforting and useful, but from a post modern perspective not true.

We have relatively recently seen the conflict between these two rival attitudes within the prison of the skull. They have always been with us, and the Athenians did not invent them. The worried public is poised on the cusp of having to make a decision which side to join.

That the primacy of faith and superstition has still not been surpassed is still evident millennia later when we consider the hostile reception to the discoveries of both Galileo and (later) Darwin.

In a trembling response to Galileo that sounds very much like the chorus of Oedipus, John Donne laments that “new philosophy calls all in doubt…The sun is lost, and the earth, and no man’s wit can well direct him where to look for it. ‘Tis all in pieces! All coherence gone!“

In a response to Darwin and to those the geological discoveries regarding the true the age of the earth, William Jennings Bryan declared to Clarence Darrow at the Scopes Monkey Trial: “I am more interested in the Rock of Ages than I am in the age of rocks!” (Inherit the Wind).

In that scene Bryan has just been shown a rock specimen that was inconceivably older than the 6000 years that Christians believed was the true age of the earth–a chronology arrived at by Bishop Ussher via his bible calculations.

We have seen how this has always been true: Regardless of century or location, one challenges powerful cultural beliefs at one’s own peril. As far as Sophocles’ chorus is concerned, to question Apollo or his interpreters, like the much later questioning of the Book of Genesis, threatens the loss of all meaning:

As the chorus declares:

“Farewell, Abaean and Olympian altar; Farewell, O Heart of Earth, inviolate shrine, If at this time your omens fail or falter, And man no longer owns your voice divine.”

And as this skepticism rears its ugly head during this explosive 5th century BCE, an anguished appeal to the heavens must be made:

“Zeus! If thou livest, all-ruling, all-pervading, Awake; old oracles are out of mind; Apollo’s name denied, his glory fading; There is no godliness in all mankind.”

Which logically leads to an invocation for a violent cure:

“Slay with thy golden bow, Lycean, Slay him, Artemis, over the Lycian hills resplendent. Bacchus,…thy fiery torch advanced to slay the Death-god, the grim enemy, God whom all other gods abhor to see.”

No mistaking it: the Plague Sophocles seems worried about is neither viral nor bacterial.

The composure of the mob unravels, and they now require an attack upon on the infidels. St. George, Cappadocian marauder and crusader, must now travel back in time to slay the dragon that represents unbelief, thus dashing human prospects.

Another of Oedipus’ supposed flaws is his rashness–the snap judgments of a Type A personality who has risen in the world, has accomplished enormous things, who is tired of standard nonsense, and who as king is entitled to demand straight answers. His pique at Teiresias is understandable. Like the Troll guarding a Monty Python bridge, the prophet offers evasive, riddling clues at first and finally—only after a deserved verbal thrashing–blurts the truth. Which to Oedipus, in these circumstances, is simply inconceivable.

In so determining, Oedipus steps away from his puppet role and speaks with a modern voice: his life, his circumstances, the very events that array themselves against him are monstrous and unbelievable. The story line, the play, everything about the popular myths: none of it is real, nor ever can be. He has now become a prisoner of the myth, a preposterous thing to consider.

But then again, nothing in the play is true, and no character can be expected to know what is going on in their creator’s (Sophocles) head. Laius and Jocasta are not real; there never was a baby with heels pinned together; there was no shepherd exchange, no transport of an infant to Thebes under such conditions. To tortuously pursue this gnarly meshwork of authorial contrivances is tantamount to using roller skates to scale a glass mountain.

Or tantamount to puzzling out the following statement from American Tiresias Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary of Defense:

There are known knowns. These are things that we know.

There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know.

But there are also unknown knowns. These are things we don’t know we don’t know.

Thanks to Sophocles, Teiresias’ performance is so unsatisfactory that Oedipus instantly assumes that he and Jocasta’s brother Creon are conspiring to replace him. It is a quick decision, rash perhaps–yet it the only thing that makes sense, the only surmise that pencils out in what we describe as the real world.

The abject chorus is un-moored by this turn of events. Not only does Oedipus insult Teiresias whom the chorus believes is “the prophet in whom, of all men, lives the incarnate truth,” but he has now accused Cleon of conspiracy.

The chorus ominously threatens Oedipus without naming him directly:

“Who walks his own high-handed way, disdaining true righteousness and holy ornament; who falsely wins, all sacred things profaning; Shall he escape his doomed pride’s punishment?…Shall he by any armour be defended from God’s sharp wrath, who casts out right for wrong?”

So it is that the religious bias of the play is more than obvious, and like all theistic propaganda, conflates reality with a bizarre mythic structure that is the story line of the play.

Because the story and its characters are phantastic creations, there is little point in totting up who said what, who was justified or not, who should have known and didn’t, who should have done this instead of that, or in asking what does a non-existent Apollo really intend? Such analysis makes sense in realistic courtroom situations, but is useless when it comes to untangling the purpose that resides at the core of this compelling dramatic tour de farce.

Oedipus is castigated for mocking Teiresias for being blind–but he is correct. The gods that priests believe in do not exist, and it takes millennia of self-imposed blindness to fabricate them and then to imagine that they control human destiny. It takes equally blind others to believe the fabricators–which is the blind leading the blind.

Nevertheless, popular criticism of the play is redolent of schadenfreude–a savoring of an otherwise supremely capable Oedipus being unable to see, while Teiresias, though blind, supposedly does see clearly.

Others express a thinly disguised satisfaction at watching this capable man stumble into the horrific mechanism that Sophocles has concocted–a writhing Iron Maiden designed by a masterful, perversely malign Rube Goldberg.

Some critics forget that had Oedipus been meek and incapable of winning his way to the kingship of Thebes, Apollo’s prophecy would have to have been fulfilled nonetheless. Even if Oedipus had not tried to outrun the consequences of the oracle and remained in Corinth, he would nevertheless commit the pre-destined crimes. Presumably, he would have had to have been kidnapped, bound, and transported in a lorry to Thebes: but unloaded briefly along the way in order to kill his father at the mountain pass where three roads meet. This is the logic of the play that critics might pretend has some connection with the useful truth.

Sophocles’ silence regarding the chronology, causes and circumstances leading to Oedipus’ predicament demonstrate that the author is not interested in these things. The drama is not a biography, is not tied to reality in any way. It is not about justice, not about merit, not about Laius’ misbehavior, not about Apollo, not about rashness or egotism, not about the consequences of over-reaching.

It is a dumb show whose masked, puppet-like actors go through the motions of a bizarre legend in order to lead us to a single, post modern question: Can a man take control of his own life?

Can men and women overcome the mind-forg’d tyrannies that cancel the possibility of human freedom?

Why is Oedipus punished for his moral choices? Why is Apollo cryptic, unhelpful and ultimately so conniving?

Sophoclean Heresy

Apollo does prevail over Oedipus: brutally and spectacularly. But in so doing, does Apollo stand revealed as a god not worthy of worship? Does Apollo’s own hubris pull down the pillars of the Olympian edifice itself?

Conventional wisdom informs us that this deconstruction of Oedipus would not have been Sophocles’ conscious intention. It also informs us that neither would it have been read, or understood that way by the majority of his audience–at least not consciously. And while there is no evidence that his contemporaries saw the play as an impiety– a judgment that they were quite willing to render in the case of certain of Euripides’ works, for example–some are less sure about its orthodoxy.

It is my view that a deconstructed Oedipus is an unintentionally atheistic and post modern play–a product of the classic age but already post-classical. Its dramatic substance points us in a new direction; a direction that could only be hinted at before this amazing 5th century BCE.

Piety and obeisance to the gods are pointless, and the gods and priests and oracles are themselves flawed cartoons. Since absentee Apollo teaches us that the attempt to take charge of one’s life is hubris, he must be rejected. He also teaches that attempts to void his power by preferring reason to submission are mistaken choices: hamar-tia.

Apollo skewers Oedipus at the same time that Sophocles unconsciously allows Apollo and his priests to hoist themselves on their own petard.

“If God is god He is not good; If God is good He is not God” (Macleish J.B.).

The unconscious after-shock of experiencing this supposedly pious play cannot be calculated.

We are licensed to think these things because of its gruesome, spectacular, step by step, pitiless destruction of a man who dares to take charge of his life. Sophocles’ Oedipus is unparalleled for its mechanical, automated cruelty.

As spectacle, presented in the theater of Dionysus by Greece’s greatest tragedian, it has the potential to become a Trojan Horse admitted to the citadel of Olympus. Samson pulls down the Temple of Dagon in order to ensure that Yahweh’s power will be confirmed; but Oedipus strikes at the designer gods themselves–rejecting their world by a supreme act of defiance: gouging out his own eyes with a brooch taken from suicidal Jocasta’s gown.

This denouement is a deliberate new wrinkle that Sophocles has added to the old myth, as well as to the previous version of Oedipus by Aeschylus. His denouement is both spectacular and self-chosen, redolent with the defiance of Gilgamesh and Enkidu who tear off the hind quarter of the Bull of Heaven and fling it into the face of Ishtar.

Of what use is sight, Oedipus asks, when everywhere all is ugliness?

Which causes us ponder: Was Sophocles of the devil’s party without knowing it?

In contrast to these disturbing ideas, we reflect on how consoling the dying archaic belief system must have once been. Live and prepare to die: then bid a tender or tearful farewell to loved ones and to the world.

The wind which blows from the tombs of the ancients comes with gentle breath as over a mound of roses. The reliefs are touching and pathetic, and always represent life. There stand father and mother, their son between them, gazing at one another with unspeakable truth to nature. Here a pair clasp hands. Here a father seems to rest on his couch and wait to be entertained by his family…They fold not their hands, gaze not into heaven; they are on earth, what they were and what they are…Here there is no knight in harness on his knees awaiting a joyful resurrection. (G.Lowes Dickinson after Goethe)

Next: Epigenesis of Totemism Or: Back to Index