Tragedy: Meet the Trojan Horse

Tragedy begins as a meditation on humanity’s relationship with destiny and with the gods. Tragedy ends by renouncing both that relationship and the gods themselves.

Our mental history has been the story of two contradictory attitudes struggling for dominance within the prison of the skull: Idealism, with its faith in eternal life, and Materialism, which accepts finitude and death as the law. One of these attitudes derives from wishes. The other derives from observation.

Both ideas arose in tandem in the earliest days, and they have accompanied us on our journey out of Africa ever since. Both co-exist within each of us simultaneously, one culturally dominant, one repressed.

The idealist point of view predominates because it offers hope for personal immortality after death. It redeems the indeterminacy of life with a vision of a timeless, untroubled eternity beyond the perishable world. In this metaphysic, death is transformed from a cul de sac into a heavenly highway.

We now know that this magical transformation has been insisted upon by the structure of the human brain and the imperatives of social evolution. It has been inculcated by culture and its religious apparatus–the dreaming brain’s secular arm. Such delusion has been both adaptive and selected for: a perfect example of the ways that serious error can nevertheless be evolutionarily adaptive.

Earlier we examined the vision darkness in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and drew parallels between the world it describes and the gobbling propensities of Brueghel’s Parable of the Fishes.

Now from this same author we shall select a speech that presents a contrarian point of view. In the Merchant of Venice, considered a romantic comedy because no one dies and the the play ends happily, the character Lorenzo directs his beloved to look up into to the night sky:

Sit, Jessica. Look how the floor of heaven

Is thick inlaid with patines of bright gold.

There’s not the smallest orb which thou behold’st

But in his motion like an angel sings,

Still quiring to the young-eyed cherubins;

Such harmony is in immortal souls;

But whilst this muddy vesture of decay

Doth grossly close it in, we cannot hear it.

At death the body, a “muddy vesture” of decay, falls away, and the soul is released for a neo-Platonic transcendence to eternity. “What dreams may come…” says Shakespeare otherwheres, “when we have shuffled off this mortal coil.”

We have seen how early on the loyal cortex–the junior partner in the body/mind duality–had been enlisted in service of the body’s project: allaying its fears, and guaranteeing its safety by elaborating cultural memes that bound non-kin together under the aegis of the Totem Father and the state.

These articles of faith were beautifully rationalized–and even masqueraded as science in their day. Lorenzo’s speech borrows not only from Ptolemy’s heliocentrism, but also from On the Heavenly Hierarchy, a work written by Dionysius the Areopagite. Both thinkers described an earth-centered universe, ringed by nine concentric spheres, rotating much like a gigantic automatic transmission through space. At the outermost reaches one encountered the Primum Mobile–a ring to which the stars were affixed.

Each sphere was presided over by one of the nine orders of angels: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Principalities, Powers, Virtues, Dominations, Archangels and Angels. The friction created by the rotation of the spheres created celestial harmony. In Eden one could hear it, but after the expulsion, Adam and Eve’s descendants became deaf to heavenly song. The message: If we live our lives as the Father requires, at death we shall return to the empyrean, and once again be able to hear the divine melody.

The study of music was prescribed by Baldassare Castiglione for those who wished to be princes. A knowledge of harmony, whose source is divine, could be translated into harmony upon this strife torn earth. One should beware, says Shakespeare, of “souls that have no music in them.” Such souls are fit for “evil stratagems” and are untrustworthy.

Human investment in these beautiful rationalizations was–and continues to be–enormous. In order to safeguard such beliefs, mind and body have carefully marshaled their forces to war discourage skepticism, atheism and materialism. Everywhere. Always. Wherever they reared their ugly heads.

We know why there was passionate resistance to Galileo’s discovery of erosion on the surfaces of both Mars and the moon. To discover evidence of change beyond earth was to debunk the myth of the perfect, timeless universe above the sublunar sphere; a universe wherein the moon shone as smooth and polished as a crystal looking glass.

We also know why there was truly substantial resistance to a later Darwin, as well as to contemporary geologists who discovered that the natural world was not created intact, not static since the beginning of time. Gravity, differential mortality, vast oceans of time and Death: these, not the gods, were solely responsible for the beauty and variety of the world. There was no master hand involved in the Creation. No Grand Artificer. No divine plan.

Denial of the fact of evolution–like current climate change denial–served its creators by preserving such comforting delusions.

Its antithesis, the voice of materialism, shall now be heard:

Crooks, the crippled, black ranch hand in Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, has seen enough of the world to know better. Living by his manure pile, a prolific reader of books, Crooks has looked deeply into life:

“I seen hunderds of men come by on the road an’ on the ranches, with their bindles on their back an’ that same damn thing in their heads. Hunderds of them. They come, an’ they quit an’ go on; an’ every damn one of ’em’s got a little piece of land in his head. An’ never a God damn one of ’em ever gets it. Just like heaven. Everybody wants a little piece of lan’. I read plenty of books out here. Nobody never gets to heaven, and nobody gets no land. It’s just in their head. They’re all’ the time talkin’ about it, but it’s jus’ in their head.”

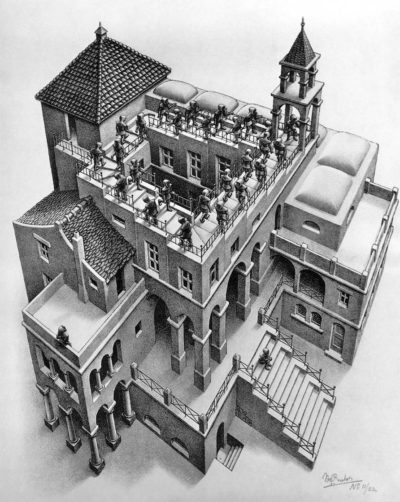

These two opposed strips of reality appear side by side in tragic literature–whether drama or fiction. They will often be arrayed against each other at its conflicted core, somewhat like the serpents that wind around Laocoon’s arms and legs. The perpetual clash of these two attitudes leads us forward to see the truth of the human condition.

The Thucydides for this Peloponnesian War within the mind is literature itself, and like the original Spartan and Athenian combatants of that conflict, they do not agree.

Consider: two cranial factories with neuronal employees numbering in the hundreds of millions. Both churning out antithetical metaphysical assertions: one definitely feel-good, the other comparatively barren. Both factories are located within the prison of the skull, and their hostile employees share the same cafeteria. The repressed hostility crackling through the noon hour atmosphere must be incredible.

The cortex that creates the myth of Osiris and which peoples the heavens with gods and salvation is the same cortex that composes Death of a Salesman, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Deer in the Works or Gilgamesh. But their respective allegiances are irreconcilable.

We know which metaphysic has always had the upper hand. The history of human belief is unambiguous about that. Atheistic beliefs have always been in the minority. No temples or cathedrals have been erected in their honor, no priesthoods created for their worship, no celebratory hymns composed and sung, and no armies organized to defend their precincts.

Atheist beliefs have always existed, and have always been marginalized or suppressed. It is not until we come to tragic literature–commencing with Gilgamesh and culminating spectacularly in the Oedipus–that un-belief begins to speak with what ultimately becomes authority.

As we have seen, human evolution and culture conspired to create this metaphysical hegemony and guarantee which would prevail. Darwin, Freud and the sociobiologists have closed the door on that inquiry. The survival value of cooperation, followership, surrender, affiliation, and prolonged infantilism have, until now, protected us on our journey. These have been among the successful strategies that kept us from being picked off by “nature, red in tooth and claw.”

Despite the lopsided array of censorious fores, tragic literature has always managed to slip that collar. Though it relies upon memes from the myths, it nevertheless takes a left turn toward rejection of delusion and toward the embrace of independence. Its perspective replaces the image of heaven with handful of dust. The resurrection insisted upon by the myths is not literal. It is mitigated, re-directed, and bound to the earth. The only resurrection now available: new understanding to carry into the finite world.

As we shall see in the next section, the myths of Osiris and Dionysus are primary sources for tragic expression, and the chassis for their unfolding is the Monomyth.

Next: Dionysus: Stampeding the Gods or: Back to Index