Kansas Forever: Finding Your Way Back Home

Man must now embark on the difficult journey

beyond culture…The greatest separation feat

of all is when one manages gradually to free

oneself from the grip of unconscious culture

(Edward T. Hall 1976)

The universality of our theme is not uncanny. Our inability to break with the errors of the past derives from our creatureliness and from the knee-capping effects of both culture and human evolution.

The harsh calculus of survival required us to acquire behaviors suitable for challenging times: We are hard wired to be competitive and readily pugnacious. We focus on tracking differences between “mine” and “thine.” We are predisposed to group (herd) think. We feel kinship principally with our own, less so with Others. We are cursed with a ridiculously easy susceptibility to indoctrination (E.O. Wilson). And just as important for group survival, we evolved a ready willingness to surrender to authority and peer pressure.

A variety of fears kept us together: fear of sliding backward, fear of exclusion, fear of failure, fear of loss or diminution, and fear of the vast unknowns–especially the impending certainty of our own death. These are the entree’s on the human behavioral menu, carried forward as we journeyed out of Africa.

Such insecurities comprise the whirling black hole that dominates the core of our religions, our stories, our legends, our “truths,” and our myths. These purely human creations are not received, are not divine, are not necessarily “true.” They are concoctions that come from deep within us; as such they hold up the mirror to the angst that is built into our DNA.

A few of our myths and tales do an adequate job of instructing us about human error. But the most influential of our memes and myths are deliberate indoctrination or propaganda. These latter are profuse, and they exist to compel belief, or to compel fervid surrender to hierarchies, ideologies or to those in power.

This is especially the case with religious and political mythology: Gods and priests must be obeyed. Leaders are specially accomplished individuals who must be trusted. National goals are always pure, democratic or beneficial. Our wars are justified because we stand alone on the world’s moral high ground. Wars waged by others are immoral and often violate human rights. The clergy, governmental officials and main stream media never lie…never fabricate fake truths or employ outright distortion to knee cap understanding. Other nations are corrupt, but ours is not. We are a Shining City on the Hill, illuminating the world with a beacon of fair play, justice, democracy and “rule of law.”

And finally: “The opposition party is the ONLY party which tells lies, distorts truths, and which has a secret agenda to control, coerce or to undermine democracy.”

This particular myth–a real whopper–has been around forever and amazingly, is still believed to by tens of millions, regardless of which of the duopoly parties they belong to. As always, when the accusative finger identifies the offender, there are always three fingers pointing back at the source of the accusation.

But what is truly uncanny–and rarely noticed–is that the deconstructed texts of many of such religious and cultural tropes undermine their ostensible lessons and purposes. To the critical mind–a rarity nowadays–hypocrisy is always present, regardless of the topic. We become so inured to dishonesty that it becomes impossible for most to discern that religious and political propaganda are designed to compel behavior, and will use any means necessary to achieve specific goals.

“If they give you ruled paper, write the other way.”

(J.R. Jiminez).

This is a post modern point of view; a deconstructionist point of view, a skeptical point of view. And this view informs us that the most important myths, legends and stories are often based upon fake news, lies, or half-truths coming from those at the top of the pyramid.

I have already described the Oedipus in this particular way: demonstrated that Apollo’s victory over Oedipus is such a cruel absurdity that it forever tarnishes Apollo and his Olympian family. We have seen that the example of Zeus’s treatment of Prometheus compels us to ask whether this divine criminal deserves our respect at all. We have identified the ticking time bomb in Euripides‘ The Bacchae. And we have conclusively demonstrated Yahweh’s low brow behavior in numerous Biblical stories–the Flood, or the ridiculous expulsion from Garden of Eden, the entire Satan fiction, as glaring examples.

Whether intended and fully conscious, or unintended and fully unconsciouous–and here Milton’s spectacular (and accidental) description of Satan’s heroic grandeur comes to mind–the story lines of such tales powerfully undermine their own apparent purposes. In thinking thoughts like these, we discover one of the wonders of the unruly neo-cortex: its latent ability to recognize illogicality, absurdity, cruelty and jiggery-pokery wherever it presents itself. And when it actually detects the message behind the lies, it accidentally blurts out the truth–much as a simple child does in the Emperor’s New Clothes.

Welcome to the questioning, to the skepticism that is at the heart of post modern thought:

Is a god who drowns the world worthy of worship?

Is a god who insists that Adam and Eve continue an infantile dependency in an imprisoning garden worthy of worship?

FAKE NEWS EVERYWHERE

So it is that “Fake News” has been civilization’s most constant companion. For millennia mis-attribution and political self promotion have been carefully inked onto papyrus, chiseled into Egypt’s red granite or into the portico of the Pantheon, inscribed on Washington’s Obelisk and Lincoln’s royal throne, frescoed onto cathedral walls–even found decorating the inaccessible, shadowy inner sanctum of Mayan temples.

Such propaganda not only blights all places of worship and arenas of governance. It also dominates main stream media, which exclusively offers “fact checked” half truths and one-sided news feeds from CIA, Pentagon, CDC, and corporate or Congressional “experts” who advocate for the elite’s point of view. No challenging questions are asked, no alternative narrative or perspective is offered. Many columnists and news anchors are Members of the Council on Foreign Affairs. So are Pharma executives, leaders of government agencies, cabinet officials–all working hand in hand to suppress honest recognition of, and fair debate of, alternatives. They are as trapped in the serpent’s embrace, just as was Laocon with whom we began our journey.

Currently, investigative reporting has vanished in the MSM, though such reporting persists on a small number of independent sites. The fiery, independent journalist whose life experiences created a passion for calling government to account has been replaced by the suburban, “mind the main chance” graduate who goes into the media for advancement, not for finding and tellling the truth. Assange prepares to die in British confinement, and no one on the Guardian investigates or questions British motivation for such treatment. Yet they pronounce daily that they are the one outlet that “brings truth to power.”

Together, such “respectable” religious and political mythologists have been responsible for all past and present Crusades, for both the the most recent and most ancient wars, and for political paralysis when it comes to climate change and destruction of the environment, and imperial depredation.

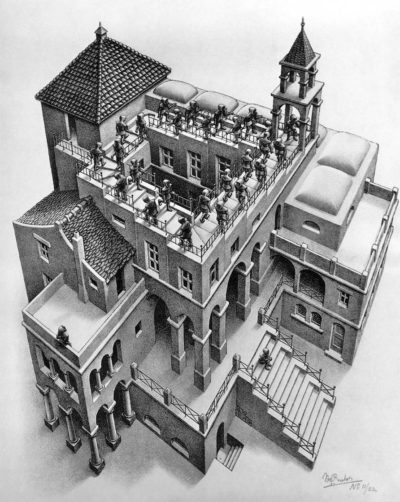

They are the architects of the sphincter of stone that Escher’s staircase–our journey through time–has become.

As Ernest Becker has said: The Urge to Overcome Evil is Often Its Father.

LEARNING TO TURN AWAY FROM THE SIRENS

Monsters like Grendel of Beowulf, and like the Humbaba of the much earlier Gilgamesh , are projections of the death fear, not death itself. Gilgamesh learns his lesson at last. Not only because his failure to resurrect Enkidu from death has been so spectacular–but also thanks to the wisdom of Siduri the Bar Maid, who advises him to Turn Away from the quest, to settle for what he has, to live humbly in the here and now, and to accept fate.

Gilgamesh, whither are you wandering? Life, which you look for, you will never find.

For when the gods created man, they let death be his share, and life withheld in their own hands.

Gilgamesh, fill your belly. Day and night make merry.

Let days be full of joy, dance and make music day and night. And wear fresh clothes.

And wash your head and bathe.

Look at the child that is holding your hand, and let your wife delight in your embrace.

These things alone are the concern of men.

How interesting that America’s recent military failures have been much, much greater–certainly more costly, more murderously spectacular–than those that Gilgamesh endured. But like the Fox with is rapacious hand stuck in the Pumpkin, America cannot rise to a heroic renunciation of imperialist folly. America’s addiction to war, regime change, the imposition of coercive sanctions upon others, resource extraction and gold, is simply too strong. America has become a dark-side facsimile of Grendel.

Beowulf’s King Hrothgar wishes to build a great feasting hall (Heorot) where he can entertain his warriors in their declining years. This goal echoes Germanic Wotan’s desire to erect Valhall, a fort he has “founded to finish all fear.” These vain desires–imitative of the hubris of Gilgamesh–are destined to be futile, impossible even for the gods who are made in the image and likeness of humanity.

The structures known as Valhall and Heorot are early iterations of human attempts to banish existential fear. As such they will soon enough morph into what is to become the cathedrals and temples of the world: all too human creations erected upon the false expectation that eternal life or perfect happiness are achievable.

So it is that Hrothgar, like Gilgamesh, cannot have what he wants–like Ahab, like Willy Loman, like Gatsby. The illusory promise is always unattainable.

Too far, too far our mortal spirits strive

To grasp at utter weal, unsatisfied.

–Aeschylus

Gilgamesh’s death-defying confidence was first disturbed by the worm that dropped from Enkidu’s nose the seventh day after his death. Wotan’s was shattered by Erda’s prophecy of doom. Hrothgar’s peace of mind is ravaged by the depredations of a bloodthirsty Grendel who invades Heorot and snatches up sleeping Thanes to appease his hunger.

Beowulf’s Grendel is the death-fear, felt in the heart of the poet at the intersection of a new Christian and a dying Teutonic culture. This fear strikes at the security and happiness of what was once a comparatively uncomplicated fireside. And now, let loose upon the world after the insecurity heightening collapse of Rome, and the triumph of a punitive, guilt oriented Christianity, the unworthiness quotient multiplies beyond all measure. It coalesces, then hurls its accumulated ferocity against the threats that individuation and “turning away” represent.

Death is the necessary end of life. As such, a natural Death is not to be feared. But the Fear of Death is.

If the fear of death is not kept alive, religious belief will perish. And when the fear perishes, the power of the state to control behavior withers.

But as all true heroes eventually learn, death is a reality against which not even culture or its gods can mount a defense. After Grendel is vanquished, Beowulf must then confront the monster’s mother; and after Grendel’s mother, Beowulf must finally confront the dragon. In this last encounter, the hero goes down to defeat, his shoulder lacerated by a venomous bite.

It should now be clear: In not Turning Away, Beowulf is also a fool; as mistaken, blind, cowardlyl and hubristic as Hrothgar. To lose his life in support of Hrothgar’s quest is his choice to be sure; and putting himself at risk for such error is the same as that repeated by young military volunteers for today’s pretextual wars.

The most valuable mythic memes instruct us that in the long run, there is simply no rainbow at the end of the struggle. The pagan poet’s heretical message is to abandon the absurd dream. This is Biff’s advice to Willy Loman: “Take that phony dream and burn it!” This advice is not always visible on the surface, but nevertheless inhabits the core of this pre-Medieval tale. A “slip” that is still evident despite numerous monastic revisions applied to the text.

Centuries later, the legend of St. George and the Dragon serves as a revealing excursion into the subtlety and power of propaganda.

Consider his record: St. George: Catholic crusader, Cappadocian soldier, fighter of infidels, then martyred under Diocletian. Here he tames a dragon that threatens a Libyan town, thus allowing the daughter of the king to put it under her control.

The dragon is yet another terrifying personification of the death fear–this time transformed into the satanic/reptilian power to kill the soul by embroiling it in sin. The triumph of the dragon–like the triumph of another Reptile–the one in the garden named Satan–would ensure the triumph of unbelief, resulting in apostasy and the damnation of multitudes of souls.

But the myth is really designed to save the Church, not humanity. It is the death of the CHURCH that the myth is structured to prevent. The terrible dragon is designed to stampede the faithful into a compliance and surrender that guarantees continued hegemony for priests and their brick and mortar, tithe receiving institutions.

All reptiles have damaged credentials, and the portrayal of the enemy as a dragon or serpent compels a visceral response that increases receptivity to the fake news contained with the legend. The true terror posed by the dragon is that it represents a renascence of paganism–a return to the guiltless, death accepting past that existed before the invention of the hair-shirt, self-flagellation, cathedrals, clergy, guilt, the stigmata and the false promises of eternal life.

So who’s side is the Dragon on?

Deconstructed, it is clear that the dragon is a personification of the atheist liberator: a return for the serpent Lucifer who opens Eve’s eyes by offering the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge. The dragon also represents Prometheus, the defiant Titan who threatens Zeus and the Olympians by bringing knowledge to humanity. These are estimable credentials–which makes it all the more necessary to adopt the reptilian form in order to provoke revulsion and insulate Yahweh from criticism.

Millennia of ruses like these help to generate a universal Stockholm Syndrome–a neurotic, fervid identification with the aggressor.

Thus, St. George fights to preserve the universal death dread that is so essential to the god creators. The dragon is evil to the warrior because it would slay the god-making propensity, and thus put the saint and his cathedrals out of business.

Deconstructed in this way, it is clear that the dragon is the friend–not the enemy–of humankind. It does not kill people, instead it murders religious faith. And interestingly, it may not be threatening to lead humanity back to the past so much as forward toward a future: and a salvation-less one at that. Humans mistake it for an enemy because they believe the orthodox mythographers and their propaganda–which deliberately mis-presents the image of freedom as a venomous murderer.

Thus George and the dragon are co-dependents, and the battle is only half-hearted. It is a scripted play, a mime that both captivates and deludes the audience. “Ritual cure can…never resolve conflict, since it is dependent on the persistence of the conflict it aims to remove” (my emphasis; Stein, 1978). That the dragon appears is necessary and good–because it enables the church to demonstrate its power by destroying it.

Not even Yahweh could slay Satan–nor could he ever want to. The existence of Satan strengthened Yahweh’s hand; indeed, the existence of Satan produced the Yahweh that later Christians have all come to know and love.

Such divine ambivalence also explains the extraordinary climax of the Christian myth–the combined episode of Christ’s brutal crucifixion, burial and resurrection was at best, and deliberately, only a cryptic triumph–not a clear-cut victory.

How easy it would have been for his mythographers to have made it such.

Inexplicably, the second-hand, un-witnessed Resurrection of Jesus occurs off stage. What was the mythologist up to? Why not have Christ rise before gaping millions? Why not have the stone that blocked the crypt blasted to smithereens, or even better, suspended aloft by magical force fields as in a painting by surrealist Magritte? Instead, it had to be reported by a handful of trembling believers, and then only at second-hand–their having received confirmation of the resurrection from a handsome stranger before whom, at the now empty tomb, they trembled and were astonished…What could they know about stones and tombs and burial shrouds? What could they believe but what they were told? And by what stretch of the imagination would a mythographer believe that we would credit their perhaps hysterical testimony?

As Tertullian and Augustine both were aware: even more incredible than miraculous events is the fact that people believe them: “Credo quia absurdum est”.

This secrecy, ambiguity and misogynistic bias serves a purpose. Its indecisiveness, its lack of concrete detail perpetuates the ambivalent polarities of the salvation project. Its indefiniteness gives rise to the doubting Thomas; gives rise to faithlessness and unbelief, the existence of which energizes inspiration for Evangels. The faithful are fed a diet of fragments and scraps, somewhat like an Isis searching for pieces of Osiris’ body. The search itself heightens the anticipation, strengthens the belief that the search shall end in success.

Since orthodox myth-makers have insisted that humans introduced death into the world via an act of disobedience, both the dragon and the expulsion from the garden must be regarded as just penalties for the crime. The dragon is but a scaly talisman: a puppet which reminds humanity of its dependency and error, and a symbol which stampedes the faithful into returning to the fold.

But if this is so, why does St. George struggle against it? Is not the dragon an ally of his god? To slay the dragon would be a Promethean act; and to kill off this reminder of human insufficiency would be a defiance of the gods. Is this what saints are for?

In the final analysis, the poor beast is not a dragon at all. It is the reality-testing propensity within the human spirit that will, if given the chance, turn away from false promises. This is why it must be slain by the Saint. It must be slain because it threatens ancient totemic arrangements. The dragon is the rebellious son untamed; he is the threatening adolescent leering just beyond the periphery of the primal horde.

But the dragon is neither dangerous nor vile. It is something much more noble; something like the Prince who is disguised as the Beast of the fairy tale.

From this point on, the dragon or Grendel will appear in the literature of the world in many disguises, returning again and again in a complexity of allegiances and mis-identifications. Most often one sees that Grendel or the dragon is on the side of culture and orthodoxy: the dragon is the agent of the gods. Danforth, the terrible judge in Miller’s The Crucible; Big Nurse, the personification of the death force in Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and so on.

LONELY ARE THE BRAVE

The modern Grendel image is most interesting when cast as an institution, a machine, or a commercial enterprise.

One superb example is Zola’s mine, Le Voreux–the voracious one. Devouring miners in huge mouthfuls, Le Voreux is the pit of despair: the ultimate destroyer of sufficiency and human happiness. The hero of the novel, Etienne Lantier, will come to this Sheol of the mining camps and lead the miners to an ill-starred but heroic revolt against the capitalist forces behind the mine–that beast to whom the Maheu family has offered up its collective life.

But there is another hero in the novel–a nihilist, Souvarine, who wearies of ineffectual political discussions and so takes it upon himself to descend alone (like Beowulf, who dives into the murky swamp in order kill Grendel), by night and without a light, to perform deadly sabotage on the chthonic timbers of the seventeen hundred foot vertical mine shaft.

“His jacket under his arm, without a lamp, he carefully went down, measuring his descent by counting the ladders. He knew that the cage caught at 1,234feet, against the fifth section of the lower casing. When he had counted fifty-four ladders he groped about with one hand and felt the bulge in the timbers. This was the place. When mine shafts were sunk anywhere between Calais and Valenciennes, extraordinary difficulties were encountered in getting through the permanent masses of underground bodies of water lying in immense sheets at the level of the lowest valleys. The only way to hold back these gushing springs was to construct casings made of timbers held together by barrel staves, thereby isolating the shafts in the middle of the lakes, the dark and mysterious waves which pounded against the walls…And it was here that lay the Torrent, that subterranean sea which was the terror of the mines of the Nord–a sea with its storms and shipwrecks, an unknown, unsounded sea that rolled its dark waves almost a thousand feet below the sunlight.”

Souvarine becomes a kind of Ninja-Freud, resolved to get at the very heart of the problem:

“It was a mad, foolhardy job, and twenty times during the course of it he almost toppled over and plunged the nearly six hundred feet to the bottom. He had to grip onto the oak guides between which the cages moved, and hanging over nothingness, he made his way along the cross-pieces that connected them at intervals–sliding along, sitting down, leaning back, supporting himself on a knee or an elbow with a cool contempt of death. The slightest breath would have sent him tumbling, and thrice, without even a shudder, he caught himself just in time.…From then on he was in the grip of fury. The breath of the unknown was intoxicating him, the black horror of this rain-battered hole throwing him into a frenzy of destruction. He attacked the casing at random, striking where he could,using the brace, using the saw, obsessed with the need to disembowel it then and there, right over his head. And he went at it with ferocity, as if he were twisting his knife in the guts of some living being whom he execrated. He was finally going to kill Le Voreux, that evil beast whose ever gaping maw had gulped down so much human flesh!”

Stephen Crane presents us with similar Grendelian images in his novel Red Badge of Courage. Only this time the monstrous personification is the army itself, a huge transference serpent that destroys individuality with the ritualized mayhem in the service of war, “the blood swollen God.”

Young Henry Fleming, drunk on romantic tales of god-like struggles, somehow imagines that participating in war will elevate him to a more than human status; will achieve some meaning or sexual attractiveness for him that is denied ordinary mortals. Once he enlists he discovers the Sisyphean tedium of army life. He learns, as does Biff, that the bright promise of transcendent heroics is illusory. It has induced him to make decisions that have seriously complicated what would otherwise have been a simple and enjoyable enough life.

At last, panicked in the first battle by an enemy charge, our hero Henry Fleming throws down his weapon and deserts. He stumbles madly toward a covering wood– a symbolic regression– expecting to find comfort in a nature whom he now (conveniently) envisions as a great, caring mother “with a deep aversion to tragedy.” But this infantile idea of his turns out to be as mistaken as his infantile idea about what the army experience was to mean. Instead of discovering in nature a nurturing mother, he finds, in a sanctuary of trees, a corpse that fixes him with its gaze. This is not the good-breast at all; rather, it is an image from the domain of Irkalla, Ereshkigal or of Kali.

Henry attempts to fly from the proximity of the corpse that bloats at the heart of the tabernacle. He attempts to fly from the vision of “the ants, venturing horribly close to the eyes.” But it seems as though the cathedral-like limbs and branches of the trees push him ever closer– as if to insist that he confront reality itself.

Henry suddenly finds his soldier’s legs leading him back to the Grendel figure of the war; back, alas, to its armies and its death-worshipping transference behaviors. He finds himself drawn to it as ineluctably and unconsciously as the miners were drawn to their doom in Zola’s Germinal:

“Then he began to run in the direction of the battle. He saw that it was an ironical thing for him to be running thus toward that which he had been at such pains to avoid…The battle was like the grinding of an immense and terrible machine to him. Its complexities and powers, its grim processes, fascinated him. He must go close and see it produce corpses.”

Henry Fleming fails in his attempt to flee from the monster. At last he himself becomes the pathetic emblem of a fiendish and frenzied surrender; activities that have everywhere been sometimes mistaken as military heroism. As is often the case with Zola, it is when Crane’s Henry is his most “heroic” that he is least in control of himself. Our hero soon finds himself in the throes of a reaction-formation: his ego masks its great terror by driving him on to ever more insane, ever more panicked feats of bravery.

The army and the war– the symbols of the authority to which humanity submits or dies–transform him into a thoughtless automaton, possessed of the “daring spirit of a savage, religion-mad.” By the end of the novel, his identification with the aggressor is so complete that his self has died.

Gilgamesh is absolutely crushed, yet experiences an epiphany: he sheds the burden of the quest and discovers how to live.

Beowulf, on his death bed, accepts defeat and the triumph of Fate:

…the great-hearted king unclasped from his

throat a collar of gold, and gave to his thane;

Gave the young hero his gold-decked helmet,

His ring and his byrny, and wished him well.

‘You are the last of the Waegmunding line.

All my kinsmen, earls in their glory,

Fate has sent to their final doom,

And I must follow.

The heroes of the emancipation project do not rise from the dead, but they do have their successors.

Beowulf’s young thane is named Wiglaf, and this role is played by Happy in the Requiem scene at the conclusion of Death of a Salesman. Earlier, it had also been played by Willy who as a young man had transferred his ego-ideal to an elder-statesman of the traveling salesman world: Dave Singleman. Singleman could journey into thirty or forty different cities and, like a Beowulf or a Gilgamesh at Humbaba’s gate, slay the buyers (dragons) every time. He was so masterful that he could achieve victory by merely picking up the phone and making the sale “without ever leaving his room.”

Singleman’s funeral parodies the warrior-studded ceremony of the Beowulf epic in all its fundamental aspects. The buyers and salesman who come from far and wide are the knights and warriors who journey to the pyre, and at the center is the young thane Willy/Wiglaf who is singled out to continue with the fallen hero’s work.

At the funeral obedient Wiglaf upbraids the guests for their failure to support their chief at the last battle and in his hour of need–a reproach that Willy flings at Biff over and over again in the course of the play Death of a Salesman.

And so it is that we are at first led to believe that the true successor to Willy’s quest will be Happy, the younger son. He chastises Biff at their father’s graveside. Biff is thanklessly abandoning Willy and his dream: he is turning away, and will soon be off for Texas and the ranch life, something Happy considers to be a betrayal:

“Biff: Charley, the man didn’t know who he was.

Happy: (infuriated) Don’t say that!

Biff: Why don’t you come with me, Happy?

Happy: I’m not licked that easily. I’m staying right in this city, and I’m gonna beat this racket!

Biff: I know who I am, kid.

Happy: All right, boy. I’m gonna show you and everybody else that Willy Loman did not die in vain. He had a good dream. It’s the only dream you can have–to come out number one man. He fought it out here, and this is where I’m gonna win it for him.”

But the hidden argument of the Requiem rebukes the concept of rebirth, and rejects the Wiglaf motif. For the fact is that Happy is as confused as is his father, and as likely to fall victim to the same self-inflicted delusions. It was imitation that led Willy into trouble in the first place. Instead we discover that the real Wiglaf of the play–the one who authentically continues Willy’s repressed spiritual quest–is Biff. Biff does not imitate so much as understand, forgive, and turn away, however. Biff knows his father’s confusion; Biff also knows what the remedy for it shall be. He shall become the self-made man, pursuing his own path, following his own particular destiny regardless of the expectations of others. No more running in panic down eleven flights of stairs for him.

Parallel Wiglaf and Enkidu motifs play an important role in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’ Nest. After mercifully suffocating the fallen hero McMurphy, Chief Broom attempts to put on the hero’s hat, but finds that it doesn’t fit. But to free himself from the land of the dead, he must fulfill McMurphy’s expectation: that of lifting the enormous control panel and heaving it through the wire mesh windows.

Here we have a variation on the dream of Gilgamesh. Prior to meeting Enkidu–the natural giant who is a predecessor for Chief Broom–the Sumerian hero dreams that “a star fell out of heaven at my feet. I tried to lift it but I was too weak. I tried to move it but could not prevail.” And while the modern hero McMurphy may not be able to lift the panel, he does manage to resurrect Chief Broom: Shamanically blowing his self-image back up so that it matches the power of his enormous body.

The world machine, the Combine, controls all events–it exists even above and beyond the nurse herself, who is to be thought of as merely its agent. But the hidden power source of the machine is the anxiety created by the death factor: Big Nurse and the hospital are at once the antidote as well as the cause of the anxieties that have been our consistent theme. The Nurse and the Hospital both are the symbolic equivalents of the idealized Mother to whom the fearful child would return–the Kali who nurtures, smothers and devours the child. The “chronics” voluntarily commit themselves to the hospital; but its purpose is not to make them better.

Big Nurse herself becomes a machine when provoked:

“She listens a minute more to make sure she isn’t hearing things; then she goes to puffing up. Her nostrils flare open, and every breath she draws she gets bigger, as big and tough looking’s I seen her get over a patient since Taber was here. She works the hinges in her elbows and fingers. I hear a small squeak. She starts moving, and I get back against the wall, and when she rumbles past she’s already big as a truck, trailing that wicker bag behind in her exhaust like a semi behind a Jimmy Diesel. Her lips are parted, and her smile’s going out before her like a radiator grill. I can smell the hot oil and magneto spark when she goes past, and every step hits the floor she blows up a size bigger, blowing and puffing, roll down anything in her path!”

One wonders what La Mettrie’s reaction to this might have been.

The prisoners in this world are pitiful creatures. Broken, intimidated, insufficient, they could not cope with the world as it is, and so have descended here where they nestle in an almost churchly refuge and receive a communion of tranquilizers and other drugs. It will be McMurphy’s task to save them from complete ego-annihilation by launching a frontal attack on the combined superego of the hospital and the world.

One of his chief tasks will be to revive an immense American Indian named Bromden, the narrator of our story. Son of a broken, alcoholic father, victim of racial abuse, dispossessed of his tribal lands, Chief has developed an acute conviction of his utter worthlessness and powerlessness. He is a mere husk of an earlier Sumerian Enkidu–the natural man; and though he dreams of fishing once again on the Columbia with his tribe, his surrender and subsequent weakness seem to have put this life beyond his reach.

In a remarkable dream sequence, Chief envisions this world and the way it really operates–a supremely cold, mechanistic universe, a hell on earth. In his dream, the ward floor descends to a basement which is the horrific underworld–the underbelly of the world that humans have made and inflicted upon themselves:

“The floor reaches some kind of solid bottom far down in the ground and stops with a soft jar. It’s dead black, and I can feel the sheet around me choking off my wind. Just as I get the sheet untied, the floor starts sliding forward…I go to clawing at that damned sheet when a whole wall slides up, reveals a huge room of endless machines stretching clear out of sight, swarming with sweating, shirtless men running up and down catwalks, faces blank and dreamy in firelight thrown from a hundred blast furnaces. It–everything I see–looks like it sounded,like the inside of a tremendous dam. Wires run to transformers out of sight. Grease and cinders catch on everything, staining the couplings and motors and dynamos red and coal black.…A workman’s eyes snap shut while he’s going at full run, and he drops in his tracks; two of his buddies pick him up and lateral him into a furnace as they pass. The furnace whoops a ball of fire and I hear the popping of a million tubes like walking through a field of seed pods”

A final image in the dream sequence confirms his worst suspicions–that the pills and other medicines dispensed by the nurse secretly contain diodes, transistors and gears, and that the more of them one takes, the more quickly one is transformed into a machine that follows the Combine’s commands. The ritualistic slaughter of one of the inmates reveals the true effects of the religion of the ward:

“The worker takes the scalpel and slices up the front of old Blastic with a clean swing and the old man stops thrashing around. I expect to be sick, but there’s no blood or innards falling out like I was looking to see–just a shower of rust and ashes, and now and again a piece of wire or glass. Worker’s standing there to his knees in what looks like clinkers.”

McMurphy is a reluctant hero for the first half of the novel, choosing to take on Big Nurse and the Combine more out of a sense of deviltry than out of any dedication to humanity. A solitary battler, he revels in the small personal triumphs he can win, and at first only pities the inmates without empathizing. The real secret of his strength, as we saw in Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound however, is that he does not recognize Big Nurse’s power over him, whereas the others do, and so pay a terrible price for their surrender.

But our hero, like Enkidu who is seduced from natural unself-consciousness by the temple Priestess, will undergo a “Fall” and a transformation. For a brief time he will become afraid of the Nurse’s incredible power, and momentarily “die.” But after undergoing his own Gethsemane his spirits revive. He will then become, appropriately enough, a diabolical personification of Christ the Savior: an anti-Christ; a Promethean figure who advocates human emancipation from the fear of death and its attendant self-negation; a Christ of the harlots and the earth; a Christ cast more in the mold of the god of the life force in all its superego unraveling splendor.

He will perform miracles as well. One will be to make Big Chief speak and regain his confidence. Like a Lazarus, Chief has lain silent for so long that his vocal cords squeak when he first tries. This is but one of the many small tests our hero undergoes in his effort to inspire the inmates by his example of heroic resistance.

An especially important scene occurs in the tub room where he takes bets on whether or not he can lift the great symbol of their enslavement–the control panel. He knows he can’t, but as a good con man, has set the bet up for two purposes: one to heighten interest in the endeavor, and the other, to return the money he has won from the inmates over the past weeks of his stay. Kesey describes the scene this way:

“Okay, stand outa the way…’Stand back sissies, You’re using my oxygen.’ McMurphy shifts his feet a few times to get a good stance, and wipes his hands on his thighs again, then leans down and gets hold of the levers on each side of the panel. When he goes to straining, the guys go to hooting and kidding him. He turns loose and straightens up and shifts his feet around again. ‘Giving up?’ Fredrickson grins. ‘Just limbering up. Here goes the real effort’–and grabs those levers again.”

We return to the image of the Laocoon:

“And suddenly nobody’s hooting at him any more. His arms commence to swell, and the veins squeeze up to the surface. He clinches his eyes, and his lips draw away from his teeth. His head leans back, and tendons stand out like coiled ropes running from his heaving neck down both arms to his hands. His whole body shakes with the strain as he tries to lift something he knows he can’t lift, something everybody knows he can’t lift. But, for just a second, when we hear the cement grind at our feet, we think, by golly, he might do it. Then his breath explodes out of him, and he falls back limp against the wall. There’s blood on the levers where he tore his hands. He pants for a minute against the wall with his eyes shut. There’s no sound but his scraping breath; nobody’s saying a thing. He opens his eyes and looks around at us. One by one he looks at the guys–even at me–then he fishes in his pockets for all the IOU’s he won the last few days at poker. He bends over the table and tries to sort them, but his hands are froze into red claws, and he can’t work the fingers. Finally he throws the whole bundle on the floor–probably forty or fifty dollars worth from each man–and turns to walk out of the tub room. He stops at the door and looks back at everybody standing around. ‘But I tried, though,’ he says. “Godammit, I sure as hell did that much, now didn’t I?” And walks out and leaves those stained pieces of paper on the floor for whoever wants to sort through them.”

By the end of the novel McMurphy has become the group daimon–much as Christ and Dionysus become the daimons for their early followers. The entire force of the group is concentrated in him, both filled with him and pouring into him the resolve to go through with the final act of his personal tragoidia.

Here the novel moves most closely to the vegetative religious origins of the Monomyth, but this liturgical ceremony will be the black mass of self-actualization, rather than mass of integration and surrender.

Early on the last day, Chief has a vision of McMurphy in the nighttime sky as a lead goose, a free spirit, leading the inmates out of the prison in Icarian formation. The symbolism is almost Christian, but the intention is anything but:

“The honking came closer and closer till it seemed like they must be flying right through the dorm, right over my head. Then they crossed the moon–a BLACK, weaving necklace, drawn into a “V” by that lead goose. For an instant that lead goose was right in the center of that circle, bigger than the others, a BLACK cross opening and closing, then he pulled his V out of sight into the sky once more.”

McMurphy in his flight, silhouetted by the moon–the terrible symbol of change on the one hand, but the ancient symbol of renewal as well. But before our hero, our daimon, can enable any of the inmates to set themselves free, he must be removed from the center of their focus so that they can properly develop themselves. He will be ordered to the shock shop for successive, punitive treatments, and spreading his arms out like a cross, he will there receive his wired, metal crown of thorns, but only after his head has been anointed with conductant.

If the information at poolside McMurphy received was his Gethsemane–that moment of terrible isolation where the hero must find it in himself to go on, find reasons to justify his tasting from that bitter cup that is the drink of the newer tradition of the unorthodox hero, then the party scene at the end is his Betrayal.

Turkel the janitor, an Utnapishtim drunk with the inmates, has unintentionally provided them with means of escape: his keys. With these the inmates open all the windows, but like Gilgamesh, McMurphy falls asleep at the critical moment before escape. At dawn the warders find them all in their drunken state. They find Billy Bibbitt too, the immature inmate for whom McMurphy has arranged an introduction to the joys of love.

Billy, awakened by Big Nurse, is found sleeping with one of McMurphy’s Magdalen friends–a prostitute–and is shamed and thrown into a panic, especially when Big Nurse tells Billy that she will tell his mother what he has done. But this prostitute is not like the temple priestess of Gilgamesh; for it is not her intention to lead this client back to the enfolding arms of the city. But Big Nurse has other plans, and her threats cause Billy, like a Judas, to betray his idol. Soon after, and realizing that this surrender is in fact a cowardly turning against himself, Billy commits suicide.

We now come to denouement–the final act for the tragic hero; the moment when the hero must choose death so that others can be taught to live. But it is a black rite; an un-Christian ceremony which does not seek reunion with a totemic other as much as it does an emancipation for the self.

It is a black religion meant to banish guilt and unify both body and mind.

As daimon of the group, McMurphy rises to the occasion because they project onto him their combined, ritualistic power. The Nurse addresses him:

“‘First Charles Cheswick and now William Bibbitt! I hope you’re finally satisfied. Playing with human lives–gambling with human lives–as if you thought yourself to be a God!’ She turned and walked into the Nurse’s station and closed the door behind her, leaving a shrill, killing-cold sound ringing in the tubes of light over our heads. The distinction between McMurphy and the group collapses as Chief discovers that the hero is a projection of their own as yet unrealized need: First I had a quick thought to try to stop him, talk him into taking what he’s already won and let her have the last round, but another, bigger thought wiped the first thought away completely. Suddenly I realized with a crystal certainty that neither I nor any of the half score of us could stop him. That Harding’s arguing or my grabbing him from behind, or old Colonel Matterson’s teaching or Scanlon’s griping, or all of us together couldn’t rise up and stop him. We couldn’t stop him because we were the ones making him do it. It wasn’t the nurse that was forcing him, it was our need that was making him push himself slowly up from sitting,his big hands driving down on the leather chair arms, pushing him up, rising and standing like one of those moving picture zombies,obeying orders beamed at him from forty masters. It was us that had been making him go on for weeks, keeping him standing long after his feet and legs had given out, weeks of making him wink and grin and laugh and go on with his act long after his humor had been parched dry between two electrodes. We made him stand and hitch up his black shorts like they were horsehide chaps, and push back his cap with one finger like it was a ten gallon Stetson, slow mechanical gestures, and when he walked across the floor you could hear the iron in his bare heels ring sparks out of the tile.”

This is McMurphy’s final battle.

In an act of mercy, Chief smothers the lobotomized shadow of the former hero. He tries on the hat, and then discards it as we have seen. After he heaves the control panel through the window, we last see him loping across the lawn, his giant strides taking him home.

Kansas Forever

Buddha told a parable in a sutra:

A man traveling across a field encountered a

tiger. He fled, the tiger after him.

Coming to a precipice, he caught hold of the root

of a wild vine and swung himself down over

the edge. The tiger sniffed at him from above.

Trembling, the man looked down to where, far below,

ANOTHER tiger was waiting to eat him.

Only the vine sustained him.

Two mice, one white and one black, little by little

started to gnaw away the vine.

The man saw a luscious strawberry near him.

Grasping the vine with one hand, he plucked

the strawberry with the other.

How sweet it tasted!

We turn at last to the simplest story of all, for it is only now that we can understand its use of an ancient remedy for the fatal disease.

It is from the familiar world that Dorothy’s subconscious constructs the mythic divisions and separations that underlie the Wizard of Oz. The ferocious neighbor who threatens her “all” (en-Toto, en-Totem) becomes her dream-like personification of the death anxiety, the evil pursuer, the existential Ms. Gulch.

The friendly traveling huckster, selling priestly cure-alls to the gullible, telling futures to the believers, becomes the omnipotent Oz, able to transform THIS to THAT, and HERE to THERE.

The existential terror of our lives attacks like a tornado. We shudder so at the prospect of death–the Big Twister–that we do in fact lose our senses. Taking to our beds, we begin to dream fairy tales to mitigate the sting of existence in this world. Something is lost; something can be retrieved. But like the dream of Enkidu, these dreams are not comforts, for they both arise from and perpetuate our anxiety.

Dorothy, like all of humanity, has a natural propensity to envision gods and Totems; the very origin of her name (dora-thea) indicates this. But always, as we have seen, the gods and their demons, the good fairies and the bad, are inhabitants of the here and now; of this ever familiar, ever changing world.

We create heaven in our imagination. We conceptualize it, separate it from ourselves, and then people it with beings and processes that we encounter here on earth. A masterful projection.

Lurking at the heart of the miracle of the Wizard of Oz is the theme of reconciliation; but as we have seen, the need for reconciliation is posited on a misreading of the metaphysical reality of the universe. We predicate our lives on the existence of an unreal division that not only cannot, but need not be bridged. Dorothy dreams that she has left home and the em-brace of her Aunty Em, but in truth awakens to discover that she never has. The entire terrifying scenario plays itself out in her fanciful imagination.

For a time she believes that she must undergo some great test of faith and courage to effect her return. But when she does successfully undertake and complete the challenging journey, she has suddenly overcome her fear. Only when she tires of the quest–even becomes irritated with it–can she be prepared to know that the great Oz is himself an imposter–a winking Utnapishtim, a fake who can no more endow the cowardly with courage than he can conjure brains from straw.

For millennia humanity has turned to its familial and totemic projections, mistaking them, their heavens and their tests for realities outside, rather than inside, the self. The wizard has always known better, though he is loath to admit it. And at last, when he steps out from behind his curtain to reveal himself as a mortal man, we recognize the familiar image of ourselves.

Click the red slippers three times.

What incredible magic the mind is capable of. What an amazing dream the mythology of existence itself has been. Philip Traum knew all of this, and says so at the end of Twain’s Mysterious Stranger:

You perceive, now, that these things are all

impossible except in a dream. You perceive

that they are pure and puerile inanities, the

silly creations of an imagination that is

not conscious of its freaks– in a word,

that they are a dream, and you the maker of it.

The dream marks are all present, and you

should have recognized them earlier.

Humanity, in this formulation, assumes all the attributes of a god, creating and refashioning its existence anew each time it encounters the world.

We awaken from the childish dream at last.

We had never left home.

We shall not cease from exploring

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

*

(c) Copyright Dr. Bruce Saari

All Rights Reserved/Use or Reproduction By Permission Only