The Monomythic Roots of Everything

Osiris, Haoma, Tammuz, Dionysus, Persephone, Quetzalcoatl, Jesus. These are a few of the gods who participate in the monomythic pattern of Loss, Journey, Test and Return. Each of these gods dies and is resurrected. Their stories are myths that derive from the miracle of vegetative renewal.

The pattern is powerfully simple: In all nature, plant ultimately withers and dies. Its seed falls into a world beneath the soil. Tested by the elements and deprived of the warmth of the sun, the seed nevertheless endures until it is miraculously resurrected in the spring.

This pattern IS the basis for all stories in world culture–yes, I said all stories. Its constant re-telling springs from a human propensity to re-enact or imitate hoped for events–much like the sympathetic magic of a rain dance. To imitate something–whether through dance, prayer, hymn or art is our unconscious way of invoking it, calling for it to work again. Imitating it as if to awaken it and remind it to return.

In pre scientific ages, this was our only way of managing such huge and important processes. The events are indeed colossal: the daily death and rebirth of the sun, the mysterious march of the seasons, the annual renewal of food sources snatched from the darkness. This is our shared human heritage, so indelibly stamped into our unconscious: The Monomyth.

These stories always show a “loss” early in the performance. Such “loss” has many forms, many stand in’s for the fact of “death.” A loss of stature, loss of love, loss of a comfortable arrangement, loss of power, loss self composure, loss of loved ones and so on. This loss darkens the world, and plunges the hero into an anguished process required to reverse the fall–or to retrieve the past. This is the beginning of the theme of nostalgia: the wish for the thing that is no longer there, no longer in reach.

In the “Wizard of Oz,” Dorothy first loses her dog Toto. When the hurricane (aka “death”) She then loses her family her family, her consciousness and finally, she completely loses her Kansas home. In the “Red Badge of Courage” Henry Fleming discovers the grim truth about war and how it slays all dreams of glory. And in “Death of a Salesman” Willy Loman surveys the disintegration of his career, the collapse of the neighborhood, and destruction of his bright expectations for his oldest son, Biff.

Following the loss–and in imitation of the planted seed–each hero must undertake a journey into darkness. While on this journey, the hero encounters obstacles to his/her desire to return. In many cases the hero may die, and this sacrifice redeems the world in some way. This is the triumph of the dying and resurrected gods. Willy kills himself, but his son is now free to pursue his dreams. John Procter in The Crucible (is ultimately sent to the gallows, but his death breaks the back of the tyrannical witch trials. Dorothy does not die, but returns to Kansas with a deep appreciation for life and family.

This latter variation–the resurrection now translated into a new understanding, ultimately becomes the most common representation of resurrection. The hero is sacrificed and undergoes a facsimile of death.–but others receive new awareness, “new life.” This is demanded by the mythic structure. But the audience is moved, and has now acquired new eyes, new understandings. Viewers may often leave the theater with moist eyes: a mitigated form of ataraxia, anagnorisis, sophrosonye, or catharsis.

The Lion King, Jim Henson’s The Labyrinth, The Great Gatsby, Moby Dick, Red Badge of Courage, Germinal, The Scarlet Letter–each and every story that can be written must follows the monomythic pattern. Provided, or course that it is not mere gibberish, but an actual story.

In Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter, Dimmesdale is a special example. He has lived his life chained by a harsh, life denying religious code. It is not until he is come alive until the mounts the scaffold to profess his humanity that he can become free.

The ubiquity of this story pattern derives from the fact that death is our ultimate end. But tragedy also teaches that he end of life’s journey is not a dead end. Instead, it becomes a doorway into new life. In such scenarios, death is not determinative, not lasting, not real. Something very important lives on.

The most widespread example of this mythic pattern is the story of Jesus. His death fulfill prophecy, and devout christians everywhere celebrate (not mourn) both Good Friday, the Crucifixion and the Resurrection. These are the prerequisites for the coming of Easter–named after Eostre, germanic goddess of the spring. As far as believers are concerned, Jesus’s sacrifice is not a loss, it is fulfillment. A god dies, and it is good. Man dies, and it is good. The dread stone that weighs us down is miraculously rolled back. This myth is an unparalleled example of monomythic Restoration.

A comparison of two famous vegetative deities will prepare us understand the background of the monomyth. It will also help us to understand the gradual evolution of tragedy. Tragedy derives from the word “tragoidia” which means “goat song”. It is named after the ordeal and death of Dionysus–whose animal representation was a goat. The goat song is a lyric of sacrifice and ultimate victory.

We will start with Osiris, then conclude with Dionysus.

Osiris

Osiris is the world’s most ancient vegetative deity. Thanks to hieroglyphics and temple art, the myth of his life and ritual has come down to us in some detail.

The symbols of this legendary deity will be the phallus–the distant ancestor of our maypole– and the bull: the draft oxen upon which agriculture depends. He is the first son of Geb (Earth) and Nut (Sky).

Other vegetative gods will have their animal symbols, the totems or associations that are essential to the life of a particular locale. Dionysus is sometimes the wine grape, sometimes the sacrificed goat, sometimes the bull. Jesus and Tammuz are both the lamb.

In mystery religions such as these, humanity’s struggle with death is projected into the arena of the seasons and the skies. For believers, the promise of renewal is writ large and miraculously confirmed by the triumphant procession of the seasons. Or the the miraculous daily transit of the sun from sunrise to sunset, then its resurrection each dawn.

Osiris’ skin color is a shade of grey green–because he is the spirit of soil and growing things. His brother Set is his opposite, and represents the season of winter or dissolution. Osiris–food sources and nourishing Nile rover flows–must always be slain by Set, the winter. This it structure of the world: the growing season, in many climes, must always be canceled by the Winter. And in the Egyptian mind, the battle between the gods represents the engine of nature–and nature’s processes are its memorial.

When Osiris is slain by Set, all seems lost. But on the darkest day of the year–the solstice of December twenty-first–Isis, Osiris’ sister and wife, gives birth in a manger to Horus, the falcon headed avenger. It is from these rural beginnings, surrounded by the imploring gazes of the animals, that Horus and other similar sons of god will be launched to do battle with Set. The story of Jesus born in a manger, the wise men pursuing the star, the ongoing presence of Lucifer–these are directly derived from the Egyptians.

And battle Set he does, vanquishing him a little each day. Retreating before the advancing sword blows, Set loses his testicles and his grip upon the world– although he manages to pluck out Horus’s eye (below) as recompense. As Set’s power declines, the sun rises higher into the sky, pushing the world ever closer to the summer solstice, the longest day of the year.

Horus is the first savior in religious history–one of a long line who bridge the gap between life and death, between extinction and renewal. As a result of his efforts the Nile again floods the land, and the season of growth returns.

Orisis’ brother Set plays a necessary role–the murdering trickster who locks our hero in a coffin and later cuts him to pieces.

Set presents a group of royal party goers with beautifully crafted coffin and offers to give it to anyone whom it might fit. Others try and fail, but Osiris is coaxed into it. And he must get into it–must want to get into it–in order to fulfill the purpose of the myth.

He must create the conditions for his impending death for the same reason that Jesus must force Pilate to wash his hands and turn him over to the mob.

Once in, Set slams the lid on Osiris and seals it with lead. He throws it into the Nile. The coffin drifts to the shore of Byblos where it becomes incorporated into a cedar or tamarisk tree that quickly grows up and encloses it–yet another coffin. During this imprisonment, Osiris dies.

Warned that the coffin has been found, Set must now ensure that Osiris is dead. He finds the coffin, opens it, and for good measure cuts the body into fourteen pieces, scattering them across Egypt. Isis sets out to recover the body parts and finds all but the genitals–which she re-fashions in gold and attaches to the corpse. Rite and ritual commence, and Osiris returns to life.

The idealistic and culture-genic goal of the myth is now completed. It makes a passing concession to reality: Osiris’ death–like the death of all mortals–is dreadful. But now the stones that weigh down the deceased chieftain–from Neanderthal spear-bearer to the sword-bearing messiah–are rolled back in a triumphant finale.

Osiris comes to us with credentials. He credited with bringing civilization to Egypt, and with teaching people the arts of agriculture and culture. This aspect of his career resembles that of Prometheus who brought fire to shivering humanity. But there the similarity ends. Though restored from death, Osiris will choose to return to the underworld for a new religious purpose: that of judging and punishing the souls of the human dead. He and Anubis ably command the keys to heaven. This, too, is the role of the resurrected Jesus.

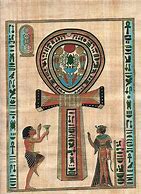

Apophis, a divine Nile crocodile, is his Osiris’s household pet, and the Egyptian Book of the Dead will describe the place to which all the deceased must journey so as to be judged. It will also prescribe the necessary formulas required for successfully approaching the god. It is here that Osiris, aided by Anubis, will weigh the heart of the deceased against a feather of righteousness. Should the balance be equal, Osiris will pronounce the word of eternal life, “Ankh,” and the soul will receive a pair of wings for its ascent to paradise.

And here is the ankh– a cross that resolves itself at the top into a loop– a combination of the symbols for the tree of life and the circular, infinity principle. The tree of life, rising skyward as it does from the depths of the earth, acts as a connector between the mythicaly sundered realms of mud and stars. The crucifix, set up on the Hill of Skulls, is another symbol for just such a tree.

Next: Stampeding the Gods: Dionysus & Arthur Miller’s The Crucible Or: Back to Index