Mythic Engine Of Modern American Culture:

The Epigenesis of Totemism

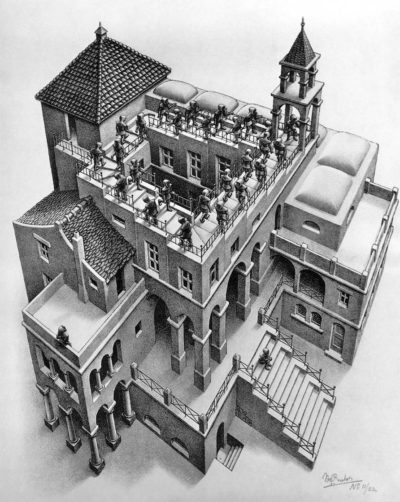

“Dogma is the imposing cathedral which lifts its dome above the beliefs and the cults of a highly organized religion, enclosing them and guarding them against the crude reality. The architects of the Middle Ages believed that such a sacred edifice was consecrated only if a living man was buried under it–a belief from the dawn of religion. Deep under the floor of the gigantic edifice, which encloses the holiest elements of a religion, an unknown fragment of reality is actually concealed. There lies buried the omnipotent chieftain of the primeval horde, who was once upon a time murdered by his united sons, and who afterwards became the Almighty God. Though the pinnacles of the cathedral may soar toward the heavens, its foundations reach down into those depths in which the strongest and most primitive instinctual impulses, the sexual and hostile impulses of humanity, have found their concealed satisfaction.” (T. Reik, 1951)

Anthropologists have long noted the ubiquity of the Totem and Taboo fundaments of culture: a legendary clan ancestor, perhaps a slain chieftain, who becomes the nexus of community ritual, and who often assumes the role of an aloof, protective animal or god.

From his wide-eyed perch at the apex of a Haida Totem pole, or from the grisly heights of the crucifix, or lost from view among the distant clouds, the Totem figure maintains his vigil, and grounds each tribal member’s conscience in a matrix of mutuality and submission. When the young are first initiated into his consensual rites, they come face to face with the permanence and inviolability of the Law.

Such symbolic mechanisms of social control are still important means by which cultures consolidate and perpetuate themselves. As Reik well knew, a fragment of reality does indeed lie concealed beneath the cathedral; and even the most sleek, high-rise constructions of aluminum and glass must still be erected upon a Totem foundation if they hope to endure.

Pyramids and cathedrals once dominated psycho-geographical landscapes, and insisted in Read-Only fashion that generations of junior offspring labor unquestioningly beneath their didactic and stony aegis. The god-kings and heroes who were entombed in sacred precincts held their descendants on a leash by an hallucinatory consensus. Mere mortals became icons, and like the parents of a small child’s world, they were were endowed with miraculous powers that an only an infantile will could bequeath. The serenity of the wheeling stars, the resurrective transit of the sun across the sky, the mystery that was the germinating seed, the success of the hunt: the very processes of life were themselves within their power to disburse and to control.

We Americans still live in a magical, though slightly more humanistic age. To find evidence of these ancient Totems closer to home, one may begin by taking a look at those icons that commemorate– and magically preserve–the struggles that issued in the birth of a political order.

High overhead, the bright colors of the riffling American flag are mixed with the potent, authoritative blood of the revolutionary sons who became, as Founding Fathers, the new Totems. The American flag is a sacred text to which one pledges allegiance, not a piece of cloth merely; and the stripes and stars that an Isis-like Betsy Ross laboriously pieced together from scavenged materials are now hedged about with ritualistic, magical force fields. Europeans, themselves the servants of many Totemic icons, should not wonder that the flag could become a significant issue in an American election campaign.

Such commemorations were once the singular textual province of the hieroglyphs chiseled into red granite along the banks of the Nile. But though these have off-loaded much of their hard grandeur to the digital papyri of the modern age, their original purposes endure: The words that are inked into modern contracts and Constitutions is a blood oath that binds the rebellious sons and their posterity to a mutual observance of the agreed upon conventions and rules. Without the invisible presence of the Totem as guarantor–or without the courts and police who are his phenotypic and secular arm– these bits of paper would carry little weight, and would be annulled on a much more frequent, and culture unraveling, basis.

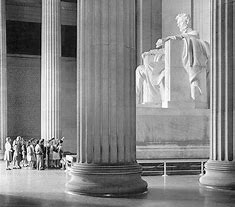

In our nation’s capitoll, the gigantic statue of an Illinois lawyer sits comfortably in the throne room of a Doric temple that only a Zeus or an Athena could have legitimately occupied in the ancient world. That he rose to power as the result of a mitigated slaying–an election–and was himself untimely slain as a by-product of internecine conflict at a super-familial level, are obvious enough. But there is more: from his seat within the hushed and womb-like sanctuary, he gazes out over an enormous reflecting pool–a national birth canal–to contemplate the distant, Moby-like immensity of Washington’s engendering obelisk. Dozens of times larger than its pharaonic progenitors, this icon towers erect from its artificial mons in primal, phallic triumph over the fecund marketplaces of a capitalistic, postmodern world.

As the mostly curious attitude of snapshot-taking tourists bears witness, one no longer knows quite what to do in the presence of such icons. They are grand, to be sure; but they are too deliberate and too stupendous to be easily introjected. Perhaps today they appear to us as curiosities merely; or as enthusiastic adolescent projections; or as contraptions designed to fabricate a Totemic heritage de novo, and that on blindingly short notice.

Their purposes seem to fail because they do not invite veneration so much as embarrassment or bemused critique. And perhaps this is because the style in which they are rendered is a relic of an age in which leaders–like the Pharaoh in his Great House–were insulated from intrusive public scrutiny, and could maintain a pretense to semi-divinity. Icons such as these, like their Bolshevik, Maoist and religious counterparts on the other side of the world, like the presidential faces of Mt. Rushmore, are perhaps the latest efforts of what is now a waning tradition of representation. They were created in response to an ancient need which still dominates the culture-makers, but created in an outmoded style. Certainly, they were produced just as the modern media lens was coming into a somewhat blurred, but ultimately hero-debunking focus.

The Icons in Washington were produced by an America which was at one time seeking a pathway to individuation, and whose people were embarked upon a journey that was modeled on the mythic heroics of ritualistic initiation. But now arrived on these distant shores, the sternly superegoistic goals of the original Oedipal quest have lost much of their allure.

There are many reasons for this, and it would take another paper entirely to begin to describe the etiology of America’s deep disaffection with old heroic patterns–low-grade media portrayals notwithstanding. And when this void opened up–represented as the gulf between the Father who ever retreats, and the Son who ever pursues (across prairies and to the sea, ultimately)–the emptiness was filled by a return to the idealized values of a much less demanding, and much more gratifying Totemic co-competitor.

I am referring now to the hedonistic fusion with the Mother, and to the escapism offered by the icons and commodities of the marketplace which are the surrogate breast: that neo-Calvinist composite of goods and services, power and appurtenances which are themselves the true emblems of godliness today, and which promise to dress the neotenous and dependent wound that was sustained by the hominids that led to us. Creatures for whom the separation from the idealized Mother and the search for an absent Father could only be assuaged by a profusion of transitional objects–the breast surrogates of the modern world.

The triumph of commodification is today the most observable phenomenon on the American cultural scene–and the plethora of advertising icons which promise release through diversion and acquisition subtly rewrites much of the Oedipal episteme upon which the American mythos was first fashioned. Marketplace values and icons irrupt everywhere in the American mindscape: today, a Marine goes to war to do a “job,” Liberty is equated with economics, greatness is wedded to the imperial ransacking of world resources and conspicuous consumption, and tabloid pages offer endless disquisitions on the salaries of professional athletes, or on the oscillations of financial markets.

The point to be understood, however, is that the chieftain and the cathedral that Reik alluded to, has not vanished. Instead, the cathedral has given way to the corporate tower, and the chieftain buried beneath is now the composite of materialistic icons and products beamed at us by a media whose sole purpose–whether delivering “news” or entertainment is to sell.

Thus, while the culturgenic face of the Totem has changed, the benefits conferred upon creatures who worship icons of one sort or another are still secure.

So it is that the Totem phenomenon has evolved and has in part, like a chrysalis or dying god, gone underground to re-emerge in a new form. The gradual deconstruction of the patriarch of the patriarch has rehabilitation of the maternal imago–the bountiful, nurturing breast–commodities–which are now a primary source of cultural allegiance and power..

The deconstruction of the Father and his fusion with the fecund diversity of the marketplace has been a gradual process. Initiation rituals that once, and of a sudden, chilled each adolescent male into the mixed blessings of adult responsibility, have over the millennia abated their sharply punitive focus. Because of factors that converged during the neolithic, most of these have since been feathered out into the smaller–but equally effective and cumulative lessons: early weaning, toilet training, Sunday school, or the teacherly admonition at recess.

The early workings of this process of decentering and feminization are perhaps best exemplified by the euphemization of ancient Dionysian totemic communion ritual. The original body and blood of the slain and dismembered god were soon replaced by bread and wine. This substitution and mitigation relativizes old symbolic constellations. Thus, while the original Oedipal Totem’s statue may still stand in the town square, the raw terror that the Father once conjured has lost its singular power to compel.

As in the cases of Zeus and Yahweh, the Totem father has been temporarily banished to Olympus, and the renascence of the Totemic Eve has undercut his purposes. The result is that the icon of the Totem Father has broken up into a myriad of cubist fragments, and these have been dispersed, like body parts of the slain Osiris, over the postmodern mind-scape in glittering profusion.

And with his slaying–and with the relativization, episteme collapse and intertextuality that are the by-products of that slaying–the consuming self itself has become the center, the focus of worship.

It is only natural, therefore, that the Totemic Mother that we all once knew and loved as children has returned to prominence, thus better to minister to the primary-processing self. She comes to us as the Ego-Ideal, the maternal counterpart to Osiris. She is Isis, the all-inclusive mother and breast; Isis, who is the forgiving alternative to the harsh trials of reality-testing and superego formation; Isis, the one who promises to the weary Prodigals of Ontogeny the instant gratification that is borne of the individual’s fusion with a narcissistic, infantile and commodified world.

But a humanist knows that Isis is also the postmodern bag lady rummaging for hidden treasures among the refuse and broken images; Isis is also the sleek and matronly suburban shopper picking absent-mindedly through the expensive baubles of the world–or restlessly surfing the pages of a mail order catalogue, looking in vain for a reflection of a lost and dimly remembered visage; for the fragments, actually, of dead Osiris’ body.

Alone, she is as incomplete as was the Father, and she knows it. And much as Isis found her purpose in gathering the dispersed pieces of Osiris’s body, so American shoppers today move up and down the aisles of a cornucopic, metacultural supermarket–or push manically at the channel selection button of their remote controls–in an effort to diffuse (and de-fuse) the singular reality of an indefinable something that has been lost.

Commodities instantly–and temporarily– assuage the neotenous ache that was a prime instrumentality of hominid evolution. And each transitional object must be paid for with a coin that bears the stamped image of a President who takes up his place in an unbroken chain of succession from the deceased Father. At a subliminal level, such tokens are very much like magical amulets: for each is round like the sun, and passes from hand to hand to bridge the gulf between reality and desire, between object-loss and the hunger to reincorporate that which is lost. Magical bits of metal such as these empower even the most feeble or crib-bound among us to command the goods and services of an otherwise inhospitable, and narcissistically damaging world. And as the inscription just beneath the portrait reminds us all: “In God We Trust.”

But to get the coin in the first place: that is the true initiation and test of one’s worth.

So it is that the modern age has magnified the mechanisms by which Totems may rule, not diminished them. Though there are more–and certainly more secular–Totems from which to choose, their very multiplicity and familiarity as the mass-produced icons of popular culture makes them difficult to critique, and thus much easier to absorb without reflection. The hunger they propitiate they also induce; and within the existential cleavage that is both the separation between and from the Mother’s breasts, one can find the alluring mirage of the Madonna, or of her sister and shadow, the vengeful Kali emerging from the Ganges. Horrifically, the Mother herself has a Janus-face, and like the Father, is endowed with the power both to confer and withhold–in short, as Totem, to compel.

A confluence of social and evolutionary factors–ontogenesis, neoteny, the powerful allure of fantasy–guarantees that Totems and Totem surrogates shall not only endure, but continue to escape critical scrutiny as well. So it is that even in the modern age archaic, magical and hypertrophized hominid behaviors and attitudes continue to be easily transmitted up the phylogenetic tree (MacLean 1972), with unchallenged, relatively unconscious, ease. “People [and cultures] become the carriers of knowledge that they do not know that they know” (Paul, 1976)–and perhaps would be slightly embarrassed about, if only they did know. The Totem persists–although the sacred and horrific visage of the original has blurred–and has insinuated itself into the complacency of the traditional and of the everyday. In this sense, the Totem has become as invisible as the world.

There are important evolutionary reasons why it will not go away, and the selective pressures that led to a “ridiculously easy human indoctrinability” (Wilson) have underwritten this Totemic evolution. So also has the increasing complexity of the data that bombards an intelligence that evolved not to test reality, but instead to navigate its way through a social reality (Wenegrat). Not only do “the limits of human rationality …[induce] individuals often to adopt culturally transmitted behaviors without independent evaluation of their [content],” but such docility can also be shown to have evolutionarily adaptive value.

It goes without saying that genes that predispose individuals to such docility (trainability) are genes that reduce the dissonance between ideology, infantile wishfulness, reality-testing and praxis. The mitigation, dispersal and commodification of the Great Issues leaves behind a residue of theoretically manageable Problems, and these are addressable through the medium of Technique (Fort, Da!).

Individuals who are thus freed from an intolerable wrestling with existential meanings are thereby enabled to conserve much needed energy for other inclusive fitness maximizing pursuits. As Chasseguet-Smirgel observes: “it is often easier to obey a set of moral principles than to become a personality in one’s own right.” The more that one can remain unconscious of the fact that he or she has abandoned the project of individuation, or is not living authentically, the more advantaged that individual shall be in his or her dealings with others and with the consensual, at times reality-denying, world (Badcock, 1987). Ignorance is not only bliss; ignorance confers survival value in significant ways. As such, ignorance is thoroughly cultural.

In sum, the assertion that will be developed, after a brief review of Freud’s Totem Theory, will be that the creation and veneration of the Totem enables each generation to discover and commit to memory the laws and values–and their misidentified extrapolations–which have themselves made the hominid transition to culture possible. As such, the propensity to Totemize has been selected for.

What is more, the degree to which Totem values are successfully introjected enables selection to operate at both genetic and at metacultural levels (Wilson 1978; H. Simon 1990). A gene which evinces a predilection for docility, indoctrinability and uncritical acceptance of the traditions is a gene which labors in service of the community good.

And the community good as we have come to know it, is a hypertrophization of a fundamental kinship altruism. The state is not a superorganism, but rather an arena in which individuals may safely work out the tiny dramas of their lives. The text for this drama, as the real evolutionists have shown, is a molecular and selective equation which, in modern calculations, not only maximizes inclusive fitness, but also, through the means of misidentification, makes possible those individually maladaptive behaviors which contribute to the evolutionarily stable strategies that the Totem has helped select for the community.

Turning Against Ourselves: The Primal Crime

Originally, this fusion of purpose seemed beyond the data that emerged from clinical practice. As Freud well knew, the edifice of culture and civilization rested upon a set of precarious–often discontenting– agreements between the individual’s desires and the collective morality.

Freud believed that civilization had long been a type of Procrustean Bed upon which each generation had been bidden to lie upon–and lie down the majority of each generation often seemed willing enough to do–even unto proclaiming the bed’s punishing comforts. Hemmed in by a multitude of conscious and unconscious taboos and regulations, cultural humanity had to forsake–or put under strict control–its sexual and aggressive urges.

One important clue that led him to an insight into the mechanics of culture formation resided in the universal presence of taboos against both incest and aggression against the elders. What Freud discovered, however, was the most shocking, perverse, and inexplicable thing: “taboos are closely associated with emotional ambivalence–that is, with a tendency to feel contradictory emotions about the same object” (Badcock, 1980).

This discovery led to the absurd and threatening conclusion that “if the taboo is the outcome of ambivalence it follows logically that the most important taboos ought…to be motivated by a correspondingly immense need to affirm [them] in the unconscious. The taboo therefore owes its very existence to a powerful, but suppressed, desire to break it” (ibid, pg. 3).

The familiar sign “Keep off the Grass”, in other words, is there because walking and running upon a beautiful lawn is desirable; one simply does not need a sign warning one to “Keep Off the Mud.” Chocolate cake is a terrifying apparition to the dangerously obese dieter precisely because it is so desirable.

According to Freud’s humanist perspective, the transition from nature to culture was a development that caused creatures to strike a blow at a significant portion of their own nature–and thus was substantially at odds with their fantasies and true desires. Hence the need for much displacement and sublimation–as well as the other ego defense mechanisms that could be rushed in to temporarily rescue a psyche on verge of anxiety collapse.

It seemed clear that the bargain that was struck at the dawn of culture–the anthropological Big Bang–could not have been gratuitous: one could simply not imagine a parliament of aggressive hominids debating the wisdom of delaying or monogamously regularizing the exercise of their primal prerogatives. One could not imagine a simian Methodist preacher threading his way from primal horde to primal horde, converting the dominant Alpha baboons, asking them to renounce their rights to the jealously guarded females, or to be nice to the male teenagers who hung leeringly on the periphery of his tyrannized band, just waiting for a lapse of concentration on his part. If these were the mechanisms that produced cooperative and cultural behavior, then we would still be picking up seeds with our Gelada cousins on the open plain (Badcock, 1980).

So how could culture occur? As Freud imagined it–the famous Just So story–the hominid transition to cooperative culture could not have been effected without a violent struggle–the overthrow of the Primal Father by his Rebellious Sons. And to prevent the inevitable explosion of internecine conflict between the triumphant sons as they bickered over the spoils, this brutal victory would have to have been instantly followed by an equally swift and overpowering feeling of remorse for the deed. Ergo, the QED for the existence of ambivalence as a constitutional reality of the human condition; and ergo the creation of the Totem, that iconic reminder of the everlasting power of the deceased Father who was both hated and admired, and who was rushed in from the precincts of the dead to enforce cooperation amongst the band of brothers. That cooperation, in this scenario, Freud equated with culture.

His account of the Primal Crime, needs no further introduction:

“One day the brothers who had been driven out came together, killed and devoured their father and so made an end of the patriarchal horde. United, they had the courage to do and succeeded in doing what would have been impossible for them individually…Cannibal savages as they were, it goes without saying that they devoured their victim as well as killing him. The violent primal father had doubtless been the feared and envied model of each one of the company of brothers: and in the act of devouring him they acquired a portion of his strength. The totem meal, which is perhaps mankind’s earliest festival, would thus be a repetition and a commemoration of this memorable and criminal deed, which was the beginning of so many things–of social organization, of moral restrictions, and of religion.”

To Freud’s way of thinking, the persistent appearance of elements of the Primal Crime scenario in a wide variety of ancient and modern cultural practices argued for its phylogenicity; and its phylogenicity accounted for its transmission and irruption at the deepest of unconscious levels. But because Freud could not adequately account for its phylogenicity–only for its obvious presence within the behaviors and mythic constellations of the generations–he was at last led to adopt the Lamarckist explanation, which ever since has hobbled a full appreciation for the insight of his view.

The result is that the Totem theory has become a sort of Totem itself–a hated thing because it employed discredited scientific theories, and because it left out so much that we now know is true (such as the co-evolution of cooperation and hunting; or the results of the computer tournaments that show that reciprocal altruism may emerge quite readily from a state of nature). But Freud’s book was also a deeply admired thing as well: so fantastic, so daring, so rhetorically sure. It was utterly preposterous and, inexplicably, deeply troubling. The facts of the event were not literally true–but the evidence for the just so truth of the event were ubiquitous.

Auditors of the tale are both attracted and repulsed by the dramatic narrative. As Paul has observed (1976): “no matter how many times Freud’s thesis is smashed over the head and left for dead, it continues to rise up and haunt its murderers and their descendants. Freud taught that to vigorously to deny or refute a threatening idea is the best way to discuss it aloud…[thus] the very number of times that the idea of the primal crime has been rejected provides ample testimony to the extent to which it is very much alive, if not well.”

That it is both alive and well today is a product of new research that–amazingly–confirms elements of both the Lamarckist and phylogenetic accounts for its creation and its transmission.

Freud was nothing if not an astute observer, and it was clear enough that behind the brick and mortar of humanity’s most esteemed cultural monuments one confronted again and again the symbolic relics and memory traces of the Totem complex and its mythemes. Axelrodian tournaments notwithstanding–the gut-wrenching persistence of the Totem constellation points to its very deep significance for human beings–a significance that goes beyond mere mythic window dressing, and which plays a role at a symbolic level that nature herself could not fill alone.

The idea of a God who is the Father, and who is challenged by his angelic or Titanic sons; the idea of a Son of God who, in being slain, himself becomes a resurrected Totem for a new religion of the Son, which displaces and slays a religion of the Father–these are just a few of the more obvious and gigantic manifestations of culture’s obsessive preoccupation with issues of sonship, apostasy, hierarchical dominance, and filial obedience.

The impetus for the persistence of the obsession was clear enough to Freud, for at bottom, the transition from nature to culture was a problem of establishing order and maintaining control–issues which are still the primary preoccupations of cultures even today. The densely redundant mythic and intellectual constellations of the past trumpeted the singularly crucial importance of this preoccupation again and again: Great Chains of Being, the divine right of kings, the revealed truths (intellectual Totems) of political or religious orthodoxy–all of these coercive, affiliative and aggression-checking embodiments of the Totemic constellation have been the evolutionarily stable, culturgenic way stations on the road to high culture.

The ubiquitous and legendary conflicts between figures such as Osiris & Set; Judas or Satan & Christ; Cain & Abel, or between Shakespeare’s Old Hamlet & Claudius seemed, therefore, less mythic than real. Unless, of course, the stories of the conflicts between Brutus & Caesar; Lenin & Czar Nicholas; Washington & George III; Akhenaten & the priests of Amon-Re; Henry VIII & the Pope–as well as the perpetual conflict between the “haves” and “have-nots” of the ancient world were themselves myths. This conflict of orders describes a battle that is kaleidoscopic and pan-cultural–and quite simply, it is the central explanatory key for historical interpretation. As such, it exactly parallels the situation that existed between the Primal Father and his adolescent sons in the Freudian scenario.

The uncanny confluence of myth and history suggests, as Freud well knew, that external strife often mirrors internal conflict–and that much of what passes for politics is motivated by antecedent psycho-political fractiousness. But what Freud could not know, but would know now, was that the rites and mythos of the Totem complex are at bottom parliamentary also; and that they are culturgenic reifications and symbolic re-codifications of the partially surpassed phylogenetic rules. These externalized, symbolic constructs and projections had become necessary when the genes off-loaded a portion of their direct control over the organism when hominid intelligence burgeoned during the Pleistocene (Lumsden 1990).

The buried chieftain beneath the cathedral was the distant upholder of those phylogenetic rules that had to be both partially rewritten and adhered to at one and the same time. As such, he was the whispering voice of the evolutionary conscience: the internally inscribed testament written by the DNA.

Reified by the Central Nervous System and transformed into the language of symbol and referent, he could continue to track his offspring, wishing them at once god speed as well as to be god-fearing as they undertook the perilous journey out of nature and into culture; and out of neotenous and dependent childhood and into a precariously socialized adulthood. His voice and continued presence were the Wilsonian leash that could recall the experiment to evolutionarily stable baselines if his children strayed too far.

Thus, at the ontogenetic level of analysis, the Totem is a projection of the protective, parental attachment figure whose proximity was necessary for survival. Such a presence was necessary for the neotenous young to physically mature, and at the same time learn to introject cultural value (Wenegrat 1990, Badcock 1987).

And as the repository of in-group ethical idealism–the product of the ego ideal which is itself a defense against the failure of personal heroics (Becker, 1973)– the Totem figure plays a phylogenetic role as well. The presence of the Totem constellation underwrites and enforces the altruistic demands that earthly parents make upon their offspring. These demands spring from the dynamics of parental investment equations, and would require siblings to exhibit altruistic behavior toward each other that far exceeds the child’s own inclusive fitness advantage (Badcock 1987, 1990).

As a superordinate parent, not only does he outlive all the generations that flourish and perish beneath his protective gaze–as does the immortal DNA (Dawkins)– but his symbolic and iconic masquerade uncannily escapes even the critical scrutiny of the adults–the very kind of scrutiny that less experienced adolescent offspring are at last able to turn upon their biological parents as part of the process of separation and individuation.

He escapes this scrutiny for the simple reason that the brain, powerful as it is, did not evolve to generate truths or to test reality for their own sake. Such modern applications of the uses to which intelligence could be put are somewhat extrinsic to its original purpose.

Rather, the Totem and its symbol producing creator emerged, as in the Oedipus myth, from the place where three roads meet. This was the ontogenetic, phylogenetic and culturgenic intersection that separated an ancient Corinth from a modern Thebes–and one could journey there only by following the sometimes narrow neural pathways that emerged from the trials and errors of the hominid and hunter-gatherer past; the very past that constituted well over 90% of the experiential history of the human race.

We can now see that the Totem is an ancient artefact designed to assist the gene in its maximization of inclusive fitness according to the rules and relationships that then pertained. As a result, the misidentifications and self-deceptions that were to play such an important role in the maintenance of hypertrophized kinship groups of later culture would go relatively undetected–they would be enabled by those co-evolutionary time-lags that induced behaviors that were beneficial for cultural formation, but which might also have been maladaptive at the strictly individualistic molecular level (Keith Sharp 1990). This cognitive gap suggests that their origins may be found to reside in the genotypic ROM, and thus they would continue to be concealed from the creature that practiced them (Badcock 1987, 1990).

As a superordinate parent, the Totem creature guards against the chaotic potentialities for peace-disturbing innovation that came along with the expanded skull packaging of the powerfully equipped human brain. As parent, the Totem looses the reins of intelligence so that new and improved evolutionary strategies could be found out. But as all parents are aware, at the same time that they encourage experimentation, they must also maintain a vigil, and must always protect the venturesome child from moving too far away from the selectively retained epigenetic rules–the particularized, evolutionarily stable strategies that have enabled the individuals within the group to safeguard their position thus far. Thus, the Totem is a necessary artefact, conjured in part by the personal threat inherent in the double edged sword of the dual-inheritance model described by Dawkins, Wilson, & Paul. In this role, he circumscribes the parameters of acceptable debate without entirely cancelling it–for cancel it he must not.

The Totem is therefore also bound; or perhaps we should say, sentenced to walk the tightrope stretched between the evolutionary pillars of necessity and experimentation. The phenotypic RAM of human cultural experimentation and invention is much more flexible than the genotypic ROM of the animal kingdom. The two-way feedback loops of the symbolizing CNS enable a much higher degree of self-correction–and error–than do the slow mechanics of differential mortality that sort themselves out in the evolutionary dialectic (Paul, 1987).

Culture co-evolved with a complex intelligence in order to maximize inclusive fitness for kin beyond the wildest of hominid dreams. But this great achievement–collaborative endeavour, enhanced food supply, greater reserves of energy to devote to the young–could succeed by enabling an unparalleled degree of creaturely experimentation–while at the same time keeping it on a leash. The capacity for complex symbolization and learning enhanced survival, and thus fulfilled the basic requirements of the ancient phylogenetic rules. For it was through deviance and error–mutation–that new evolutionarily stable strategies could come to the fore to be tested.

But most surprising of all, such advance would be made possible principally through the mechanism of creaturely ambivalence that Freud had already identified in the clinic: the testing and resistance phenomenon we referred to earlier. To innovate in the cultural mode, the existing order and paradigm had to be tested, surpassed or slain.

But not by too much–and hence the evolutionary basis for the persistence of ambivalence. There are no totems in nature; only phylogenetic rules. But for a creature who is the beneficiary of the dual-inheritance model, the symbolization and continued relearning of these rules at a conscious level becomes necessary. Thus, the icons and symbols of the Totem constitute a kind of cultural–and culturally variable– RAM that compels the performance of the consensual, inclusive-fitness maximizing strategies which the Fathers of a specific culture have devised–with the unquestioned aid of natural selection–for the perpetuation of their genes.

So it is that in fabricating the Totemic culturgen human intelligence has fused the antipodal elements of both compliance with the phylogenetic commandments, and the defiance of these very rules at one and the same time. If the Will of evolution is the will of Zeus or Yahweh, uttered from the helical Olympus or Burning Bush of the genome, then it is also the Will of the rebellious Prometheus who would undermine the false gods and create a new heaven, a new earth.

Submission and defiance were the twin halves of the hominid evolutionary Tao–the need to change and adapt and be creative on the one hand; but the need at the same time to somehow preserve those time proven evolutionarily stable behaviors that might still be of help in effecting the transition to the untested and the unknown. Hence, the innate human predilection for attachment figures, transitional objects and the like (Wenegrat 1990).

The drama of life and the drama of culture known as history are both subject, therefore, to a script whose essence is conflict, tenuous truce, and the renewal of hostilities. As such, personal, inter-personal and inter-national histories may therefore be read as kinds of repetition compulsions which may be modeled after the dynamics of the instincts as Freud originally defined them. They are conservative, restorative and regressive engines. But again, the Oedipal mutant mythologized as Prometheus, the defiant one, the breaker of the rules, the violator of the hierarchies, is also in our genes. As Christopher Badcock says: “We have an Oedipal complex because we evolved it.”

Culture, as Freud knew, was repressive; but it was repressive precisely because it was founded upon a nature that was itself, at bottom, repressive. The anthropological Big Bang did not strike at human nature so much as fulfill and symbolically sketch out the rules of the game that formed the backdrop for all life. The rules of survival had winnowed maladaptive innovators or deviants who strayed too far from the menu options allowed by an ecologically niched ROM. Even the all-inclusive mother of infantile fantasy was at bottom repressive: a fantasy merely.

As such Freud’s primal crime scenario is a reprise of ontogenetic and phylogenetic history both. It is a celebration of triumph, and a warning as well. The creation of culture was the symbolic slaying of nature (the phylogenetic rules) in mitigated form (Paul, 1987). The fruit of the experimental victory was the high culture and cooperative effort that created new categories of affiliation beyond biological kin; and the warning was that to survive, the memory of the Totem must always endure.

The task of maximizing docility and indoctrinability, the old domain of the phylogenetic ROM, has therefore been off-loaded onto culture to an unparalleled degree. To use Badcock’s technological imagery, the function of symbolic projection of the Totem was to return the conscious, free ranging cursor from the RAM to its unconscious roots–the ROM of the phylogenetic rules. Totem figures are charged with the task of canalizing thought and criticism that could lead the creature too far astray.

This evolutionary predicament, and the contortions required of a creature who is somewhat divided against itself, are not so much a mistake in the programming as they are a manifestation of the evolutionary gamble that is part and parcel of the genetic off-loading that Lumsden refers to. Thus, the rebellious and paradigm challenging virus that fills the flashing cultural screen with the docility-slaying image of a heretic or a rebel is a actually a virus that invokes a subroutine of the original Totemic program. This subroutine–political, philosophical and other forms of cultural experimentation (including the postmodern condition)–encourages some few creatures to push to the outside of the psycho-phylogenetic envelope. If what they find out there beyond the pale is advantageous, then the virus will ultimately be selected for in the evolutionary round.

This potential for addressability and creative variation of the fundamental Totem-text accounts for a significant amount of the cultural variation which is extant in the world. It also accounts for much of human history–especially the HOME command that, in Talleyrand’s and Santayana’s formulation, compels the repetition of the historical pattern. Nature’s creatures experiment with the “deep fabric of life” at their own peril.

The struggle for dominance, the preservation of territory, the maximization of inclusive fitness on the kin altruistic model–these were the polar stars by which creatures had navigated their way through a primordial Scylla and Charybdis: the harsh selective calculus of the preceding aeons. Obeisance to these tests and navigational guides were precisely those evolutionarily stable strategies that brought us here. Packaged as symbols and passed unconsciously up the phylogenetic tree, they became the transitional phenomena that our hominid ancestors could not discard as they journeyed out across the African plains and into the future.

Arrived at last at the threshold of the modern world–the world of language, symbol, linguistic deceit and phantom misidentification–the ancient program of our barking and basking ancestors was hypertrophically reified and projected into the heavens, or into their earthly surrogate: the state. Creatively reinterpreted by the playful and devious neocortex that could only be the by-product of neotenous human development and prolonged dependency–and thus predisposed to Totemic mythemes–they naturally and variously appeared as the national anthems, the pledges of allegiance, the Great Chains of Being, and the mythologized Founding Fathers of the modern world. In the words of St. Paul:

“Let every person be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God.

Therefore, he who resists the authorities resists what God has appointed…For the same reason you also pay taxes, for the authorities are ministers of God.”

An Alpha Baboon would find himself in complete agreement with sentiments like these. For he would intuit–as now we clearly know–that had these sacrifices and laws not been obeyed–exactly as the animal Totem or anthropomorphosed Father commanded–then neither of us would be here to read or write this now. To submit to the law was to fulfill His will, and to fulfill His will was to strike a bargain with the unseen powers of evolutionary providence.

The Totem, in other words, was not the product of a catastrophic event rooted in time. Instead, it was the reified image or composite that emerged from a forgotten series of selective processes that elaborated gradually from the travails of experimenting cooperative groups. The Totem derived from fundamental evolutionary transactions negotiated on a wide scale by those Pleistocene ancestors of ours who would become the culture bearing progenitors of the human future. We are their descendants, and they continue to clasp us hard.

As Freud intuited so profoundly: a war had been waged; someone had been defeated; there were remorseful (ambivalent) victors in the struggle; and their victory had been symbolically renewed within the mental organization of each successive generation.

“In the beginning,” Freud insisted until the end, “was the deed.”

Next: Ecce Homo: Nightmare in Eden Or: Back to Index