Why History Must Repeat, Repeat, Repeat

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour. (Wm. Blake)

William of Champeaux, teacher of Abelard, proposed the idea that the universal is contained in the particular. To know the little world or microcosm is to know the larger structure of which it is a part. Ergo: in order to know humanity it is really only necessary to know one individual.

Perhaps a modern Champeaux would also argue that one droplet of pond water beneath a microscope would reveal as much about human motivation than an entire library of explanations.

True enough, large worlds (macrocosms) derive their characteristics from shammer worlds (microcosms). The unique character of the constituent parts, or of the tiniest of laws operating at the subatomic level anticipates, structures and shapes the operation of the larger whole. A man can be reconstructed from an infinitesimal genome, and today’s invisible collisions in a particle accelerator replicate the origins of the universe fifteen billion years ago: the Big Bang.

Like Occam’s razor, such reductionism enables the student to cut quickly through masking rhetoric to get a closer look at the visage of the past. Perhaps some important details will be lost; but doubtless, the essentials of the pattern will not be mistaken: human history is regressive and repetitive because it is enacted by creatures who are compelled to “represent and perpetuate object relations that have been disrupted by death or other forms of loss” (Stein, 1985).

The ubiquity of the theme of both the loss and the journey in human mythic productions reminds us of phylogenetic and ontogenetic realities: all creatures undergo development and change. This is true in terms of their evolutionary history, as well as in terms of each individual’s development within the womb and within the world. All life is–and always has been–on a journey, and the journey is often equatable with change, or loss.

The ineluctability of the journey is a red-hot stone that hisses down into the core of one’s being. Motion or change may often themselves be the enemy, and these phenomena give rise to the one structure that unites all human stories: the Monomyth.

The loss, journey, test and return that form the thematic scaffolding of the monomyth mirror the frequent changes that occur in each human life. The loss of the comforts of the womb is replicated in countless changes as one journeys forward: changes in the degree to which one replaces innocence with experience, changes in one’s levels of self esteem, changes in love or its objects, changes in all sorts of relationships, alternations between success and failure–and ultimately, the ageing process and the triumph of death.

The myriad losses or alterations experienced by human individuals, and the meliorative journeys and tests to which they give rise, are projected and replicated in larger mythical contexts: the loss of the Golden Age, the Loss of Paradise, the loss of Heaven.

The commandment to undertake the journey is underwritten by a variety of visible texts: the journey of the sun across the sky; the sequence of the seasons; the journey of the hero to the underworld; the journey of each individual toward death.

The hunger to restore the loss encompass a manifold variety of ways to recapture the womb: from the guns fired in service of holistic conceptions of culture, to the prayers uttered in the darkened sacristy before the golden idol or the shimmering votive candle.

One’s psychic orientation creates the meaning and pattern of the world: the givens of internal politics become the givens for national politics and are often projected to the heavens. “Men and women,” says Howard Stein (1986), “fashion the world out of the substance of their psyches from the experience of their bodies, childhoods, and families; they project psychic contents outward onto the social and physical world, and act as though what is projected is in fact an attribute of the other or outer…Projected outward, the fate of the body becomes the fate of the world.”

If humankind lives in a world where change/loss predominate, then much of life must be conceived of as a resistance to reality; a kind of war.

The reality of this is reflected even in terms of the way we conceptualize the elements of the body. The skeleton is the rigid framework of law and order; the musculature, intestines and the closed fist the economic engine and military power; and the white corpuscles are the interior police guarding against domestic chaos. And the virus? The virus is the alien; the revolutionary; the assassin who slays the head of state: the change that one cannot control; the change against which we continue to prepare to resist.

But the tenor of the analogy derives from the first and smallest world: the cell organizes itself into a fortress that preserves its integrity against assaults from the outer world.

All life is locked in a struggle to maximize its fitness and to enjoy its space. Stroll through any old growth forest. Recollect while there that the calm emanating from the great patriarchs is that of the victor who settles down to the feast after the dusty exertion of the kill. Centuries before your brief visit to these silent, slavering trees, the forest had been the scene of a solemn gladiatorial combat. Grasses and ground covers were the first settlers on the barren land; but these were soon overcome by woody shrubs. In time these shrubs suffered a slow and sunless strangulation beneath the enshrouding limbs of the deciduous hardwoods; and these triumphant hardwoods at last were pushed into a botanical Babi-Yar by the towering conifers.

Nowhere is the repetitive rolodex of existence more clear than in the story of humanity’s political experience. Governments do seem to change their form through time, passing, as do generations of organisms, through elaborations upon primitive themes. But though the outer disguise is in a state of perpetual change, the inner driver remains the same.

The elephant is not a sea worm to be sure, but its purpose in life is no different, and its supposed superior abilities are merely adaptations that are useful for the conditions in which it finds itself. Should the seas inundate the earth in its entirety, the elephant will have to reach back into its ancestral memory to learn to become a sea worm once again. And the reach will not be all that far, though it will be impossible.

As the elephant carries its ancestors around with it in its genetic endowment, so do the most modern governmental forms carry within themselves the components of the past– which means that the past isn’t really “passed” at all.

“Government has been a fossil;

it should have been a plant.”

(Emerson)

Voltaire’s Sirian giants would be blind to the fine print of human disagreements, as well as to the various slogans and metaphysical bunting which these self-deceiving creatures use to dress up and excuse their repetition compulsions. To see human political (and personal) conflicts for what they are, a Sirian historian would look through the righteous posturing, and at the same time he would turn down the volume of the shining oratory that is the stock in trade of all states that are on the prowl. Speeches, for example, about “freedom”, or “self-sacrifice,” or the supposedly disinterested pursuit of visionary, world-saving goals: a New World Order.

Such promiscuous rhetorical altruism–a sort of self perpetuating, onanistic kinship projection–would be interesting, but it would instantly be seen as a mask for other motives. Under this Sirian’s scrutiny, humanity’s beliefs and behaviors would be naked at last.

And this would be what the giant reductionist saw: human beings are creatures locked in the struggle to survive and replicate their genes by whatever means possible.

At an unconscious level, humans are motivated to maintain their individual organismic integrity–just as the amoeba is. This is the first commandment for successful gene transmission. But given the perverse complexity of human psychology, a person’s genetic success has as much to do with how she feels about her situation and her powers as it does with her ability to attract mates, or to surround a food vacuole or an economy-sized tub of fried chicken.

The result is that a subjective–and potentially phantastic–variable is inserted into the human survival equation. Satisfaction becomes impossible to quantify; victory is not always clear. Thus human actions are not always “straightforwardly explicable in terms of [their] fitness-maximising benefits, (Keith Sharp, 1990)” but may also be referenced to psychological misidentifications which nevertheless have “some significance for the biologically rooted motivation which [they elicit].” Humans can be satisfied with illusion; and illusion, or the maintenance of delusion, can replace fundamental fitness maximizing activities.

People can lose their minds; people can become mad.

Welcome to much of human history–a drama where the humanist investigator is compelled to ask again and again: How much food is enough? One wildebeest? Two? Or shall the tribe lay claim to the entire habitat so that its supply of wildebeest shall be guaranteed even for generations yet unborn? Perhaps it needs a wildebeest buffer zone? How many missiles are enough? How much wealth? How many aircraft carriers?

A struggle between states to create and secure such a zone would be driven by a hunger not only for food; but for control of the future, and for the peace of mind that such control would bring. So it is that humans, as future-anticipating animals, can kill each other for offenses or threats that have not yet come to pass: the war to prevent a war, in other words.

I think there is no way to calculate the effect that this brain capacity has had on human history. The ability to conceptualize creaturely concerns, and then to amplify or project these into the future by a purely mental act, may turn out to be the biggest of curses. A lion who goes for a time without food is hungry merely.

Yet homo sapiens can rise from a Trimalchian feast and still be burdened with spiritual hunger, with anxiety.

“In a sense humans are unique among animals in that our behaviors appear liberated from the tyrannical demands of biology, mediated by natural selection. We can substitute personal satisfactions for adaptive significance…[with the result that] we have been selected to engage in them. We find them sweet (Barash, 1977).

This statement puts a nice face upon a basically dangerous and out of control situation. In much cultural life, the “what might be’s” can come to predominate, and more and more the agenda for action may therefore become preventive or anticipatory–and potentially phantastical. The battle between the earliest humans over a kill or over a hunting territory is about maximizing fitness at a purely physical or metabolic level. But Hitler’s drive into Russia, the Crusades, America’s war on Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, Ukraine, and soon with Chine, or the ubiquitous conflicts between religious faiths: these efforts to fulfill a projective destiny (and satiate a self-created mental hunger) balloon life’s basic problems beyond all measure.

So has the level at which conflict/threat is calculated. As affiliations grew, humanity’s kinship obligations–both real (genetic) and fantastical (cultural)–spread. Now it became possible for young warriors to sacrifice their lives for a country or a cause which, patriotic boosterism notwithstanding, one had no deep connection to, or sympathy for.

Returning draftees who served in Vietnam were shocked to discover that some of their fellows at home were appalled by their participation in the war. And so, when they returned home, they were often greeted by silence or jeers.

Those who surrendered to the draft and were forced to risk their lives for the reified nation felt betrayed by the very citizens whom they had been led to believe they were defending. The terms of the kinship contract they reluctantly entered into had been changed.

Cultural manipulation of information and governmental projection of phantom threats are to blame for such temporary breakdown–the ego-ideal cannot be turned against the self for very long and still retain its attractive and manipulative power.

But the skillful deployment of lies and half truths nevertheless guarantees that the unnatural struggles will go on. They also prevent many from seeing that the enemy is most often the willingness to go to war itself; which means that the enemy is also the youthful, bright-eyed, patriotic eighteen year-old Marine or Kamikaze pilot on your own side. The 18 year old cadet who, if commanded to do it, turns his weapon upon his own people.

Such a vision is rather hard to come by. This is because the investure of parental authority in the state (motherland, fatherland) a-priori infantilizes its citizens; and the projection of kinship into the galaxies (we are god’s children) lifts conflict from its biological and organic roots onto a macrocosmic and metaphysical plane.

Everything the metaphysical human Midas touches turns to meaning; but the endless multiplication and reification of meanings retards choice and action: “[Until] custom lie[s] upon thee like a weight; heavy as frost, and deep almost as life” (Wordsworth).

Strange metaphysical propositions appear everywhere on menu for the banquet of life; and not all of them spring naturally from human biology.

Many, as we have seen, are culturally orchestrated. Not all wars are fought for ideology; but almost always the rationales for wars are presented and sold as ideological. Propaganda is as old as humanity itself, and the portrayal of the enemy as someone less than human, as someone who threatens all good values in the world is really much more effective in motivating young men to kill or die than speeches about food, power or land would be. Sam Keen’s penetrating Faces of the Enemy details the many propagandistic methods states use to nurture hostilities. Kill the shadow so that the heroic self can shine through.

But when young soldiers discover that a given war isn’t really about a god’s will, or about some goodness in the abstract, or not even very much like the falsely heroic Hollywood portrayals have led them to expect, they become demoralized as they did in Vietnam, as they did in Iraq, as they did in Afghanistan. Truth and reality are dangerous for warriors on all sides; simplistic sloganeering and paranoid delusions are nourishing food for heroes.

This dreadful competition between nations is history’s favorite story line. But the rivalry between states is a secondary phenomenon that only hints at the presence of a more elemental combat. This can simply be described as the struggle both within and between individuals and their own cultural system to determine who shall rule.

So history misses the point when it details movements of troops. One must remember that armies are mere pawns: forced associations of mostly too young, mostly callow men bound together either by mutual terror of the authorities, or by the simple need to escape the routine of daily life, or who are held suspended above and out of truth’s reach by a heroic, propagandistic lie.

Rare is the soldier who knows the real agenda of a war policy, and those that profess to know are probably only aware of their own state’s biased, self-serving rationale for the conflict. A post-structuralist visitor from Sirius might apply this observation to the works of most historians as well, and so would discard their hair-splitting, thickly annotated texts.

Long ago it would have become clear to even this stranger that by the time a nation’s military receives the command to invade, the really important battle has already been won–which means that it has also been lost.

The real drama of history has little to do with the struggles between nations. Instead, the battle lines are first drawn within the self.

The repetitive pattern of history strikes us full in the face when one considers the compressed events of the French revolution. Its collapse was unbelievably swift and spectacular. But short of the standard variety of causes, conventional history is powerless to give us a really useable and informative answer: instead, it just “proves” the pattern.

And for many, the pattern of the French revolution looks like this:

1. MONARCH

2. REVOLUTION

3. REPUBLIC/TERROR

4. DICTATOR

1. MONARCH

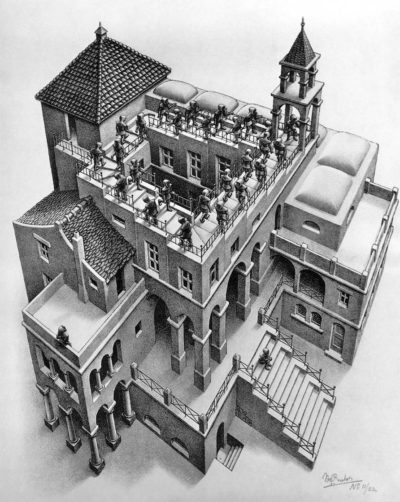

Here is the great historical dilemma squeezed into one generation: the reversion to archaic forms, the ascending- descending Escherian round, the frustration of all dreams for a new age.

The exultant Jacobins imagined that they had broken with the past, and in the heat of their idealistic enthusiasm prepared for the new world and a new menu by renaming the months, burning their history books, and abolishing the old, discredited gods.

And what beautiful names those new French months had: Germinal, Floreal, Prairial, Mesidor, Fructidor, Vendemiaire, Brumiaire, Frimaire, Nivose, Pluviose, Ventose.

But what the revolutionaries could not do was to transform the looping psycho-biological mythos that for millions of years has governed the world–indeed, which even governed the course of their revolution. The strength of this mythos had ill prepared the masses for freedom, and they yearned for a king within a decade of killing the one they had. The strength of this mythos also drove the revolutionaries to a fatal extremism in the name of purity–the Reign of Terror. The revolution teaches us that while the superego had been diminished, no systematic attempt at preparing the ego to heroically expand its scope and fill the void had been undertaken.

How prescient was Freud in his “just-so story” of the slaying of the Primal Father in his Totem and Taboo:

1) Father Rules (Louis XVI)

2) Sons Rebel / Father Slain (Bastille; Regicide)

3) Sons Fight Each Other (Terror)

4) One Son Emerges Victorious (Napoleon)

1) Father Returns to Rule (Bourbons)

Not even Robespierre clad for the feast of the Supreme Being in his new coat of robin’s egg blue could make humanity over into beings deserving of such a paradise on earth. At least, not overnight–no matter how sharp he kept the guillotine. Instead, the Revolution unleashed forces that pushed it into a familiar terror, and the mind was shocked to witness, in Napoleon, the return of its ancient enemy to the throne. He had hardly left.

Again we recall Will Rogers’ Ecclesiastean pessimism about the newness of political process. And so far, his belief that to have read one newspaper is to have read them all is an accurate estimation of what humans have been up to since the neolithic revolution. There is an immense conservatism about human behavior; a conservatism which, in its preference for ritual observance of the pieties and rules of the game of life, links us more closely to the animals than to the stars.

One manifestation of this conservatism is the fact that states–whatever the variety– have always sought to consolidate what “is.” No matter how radical their origins, states inevitably institute laws that are designed to perpetuate themselves in their present form– they attempt to freeze the menu in situ. Countries that were born of violent revolution–America for example–soon pass laws outlawing revolution against the post-revolutionary status-quo.

There are even more subtle ways that culture can block change. Perhaps the unwritten commandments to conform are the most dangerous, simply because they are less obvious and go undetected by most citizens. Certainly they are the most effective: unwritten cultural dictums inculcate respect for existing systems, thus rendering criticism of these systems unlikely in the first place.

In America the widespread adoption and recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance, a statement of patriotic faith that first appeared in a children’s magazine in l929, has gone a long way toward curbing new challenges to authority. The Young Soviet Pioneers had a similar pledge. The givens of all systems are imprinted on youth at the earliest of ages, and thereby act as an a-priori form of censorship that limits the freedom to entertain culture-challenging opinions.

Brute nature also discourages individualism in animal groupings.

Despite the fact that struggles between individuals within the herds are frequent– the butting rituals of rams has become a visual cliche’–the goal of these contests will not be to create a new revolutionary order, or a new set of emancipating values for the group. Instead, the purpose of these conflicts will be to continue the ancient pattern–old herd leaders being replaced by new, more vigorous ones who then continue to perpetuate the instinctual customs of the herd. Power will shift; wealth or access to mates will be temporarily redistributed–but the archaic patterns will prevail, regardless of the change in personnel. No creature, in other words, fights to bring an end to its fundamental animal nature as it is presently constituted.

This suggests to us just why there are few new ideas on the political horizon. The most dangerous proof of this assertion can be seen in the ongoing surrender to the hypnotic panoply of national symbols. This surrender to the icons of authority– for example, the manic American reverence for the flag– is sacramentalized as patriotism. But it is here in its practice that humans come closest to the animals and to those instincts that for eons have knit groups successfully together.

According to existential psychoanalyst Ernest Becker: at the core of each human being there resides a certain knowledge of one’s ridiculous, impotent, finite creatureliness. It is this repellant vision that compels people, much to the chagrin of rationalists and anarchists, to project a kind of divinity onto their leaders and their national icons. At last these become the objects of public cults, and in their superhuman images and actions some find assurance that the nation they have identified with will endure despite the inevitable deaths of the individuals that compose it (Chasseguet-Smirgel).

This drivenness to deify the nation–to celebrate the holiness of its past or the singularity of its destiny–manifests itself in the lyrics of its hymns, or on its coinage, or in the grandiose proportions of its governmental temples. Such practices have always been a requisite of culture, and the prevalence of this socially encouraged habit helps us to understand why humanity has had difficulty reinventing the future. It also serves to highlight those few revolutionary innovations that have, against all odds, nevertheless appeared in an otherwise unfurnished political landscape.

One curious instance has been the American idea of the separation of church and state.

The odds have always been against its ever coming into being. For centuries, to violate the Pope’s peace was often to violate the king’s peace; and both St. Paul and Christ counsel the faithful not to rebel against secular authority, calling upon them to render even unto Caesar when Caesar requires. And so it is no wonder that religion has been seen as the enemy of liberation by a few of history’s revolutionaries. But as we have also seen, this attack upon religion is itself an externalization and scapegoating of the problem. The church exploited creaturely ambivalence and angst it is true; but the church and its priests did not invent these.

Thanks to ambivalence, humanity has on occasion been able to produce memes that temporarily slip the collar. Yet, the separation doctrine has been undermined so often and in such subtle ways (One nation, under God…In God We Trust…), that its spirit has been eviscerated in less than two hundred years–relegating it to the status of a curiosity; a relic; a dead letter which can block a Nativity display in a small town, but which is powerless to address the larger questions that we have just hinted at.

When I say that humans have “slipped the collar” to a partial extent, I am referring to the fact that in every generation the species manages to produce a few individuals who acquire their meanings by taking up a position outside the culture value system. They remind us what humans might be capable of becoming, again via the pathways opened up by ambivalence.

To question cultural values and goals is to question the very meaning of life as each culture has defined it. To do this is to move toward freedom, but it is a freedom surrounded by terror–the terror of having to invent one’s own meanings. The Prodigal Son distills for us this ambivalence: this journeying outward into the void, and then the panicked return to the safety of the tried and true.

But even here the complexity and deeper level of human entrapment will not go away, and a Freudian might claim that the individual who is not effectively socialized, and whom we mistake for a kind of independent hero on an outwardbound journey, is in fact a victim of his own upbringing and incapacity. Perhaps he is merely acting out, or being driven by, the after effects of some forgotten trauma that has made affiliation a personal impossibility. Wenegrat, for example, argues that perhaps atheists have such problems, and are as driven to disaffiliate with the imago of the Father, much as dependent religionists are driven to affiliate (1990).

The key word here, of course, is driven.

Humans may walk upon the surface of the moon, yet they still instinctively recognize a hierarchy in which they have to find their place, as well as physical and psychic territories that they can occupy only at their own peril. But their peculiarly neocortical capacity to envision the future, to imagine, to speculate about what might be rather than what merely is…this is MacLean’s point about the evolution of the prefrontal editor.

These characteristics, whatever their source, enable some few members of the species (in every generation) to step outside the process of history and to regard it with a skeptical eye, much as Escher’s solitary monk, standing alone and apart on a lower balcony (Ascending Descending), who silently observes the sullen march with which we began our journey. We cannot account for the disaffiliation or its causes–yet one cannot ignore the potentials that it represents. Disaffiliation may be a natural product; but then so is a white blood cell.

It seems that the very conditions of life were themselves at first arrayed against emancipation of the human intellect. While the democratic tradition may arguably have been the first political form born in the earliest tribes, it was not the most long-lived. The need to organize irrigation products on a vast, cooperative scale forced the first civilizations to resort to theocracy–the rule of priests who spoke for the god– to achieve the cohesion that was necessary. The height of the pyramids and ziggurats are inverted indices of human freedom. So is a cathedral; so is a palace; so, perhaps, is a corporate or a university tower.

But again, we confront the ever-changing pattern insisted upon by the governmental menu; the almost manic restlessness that seems by its very insistence to prophesy some potentially liberating truth.

But we must ask: How, in one short moment, can a political leader or program be expected to effect sweeping transformations in the beliefs and expectations of its citizens? How can political innovations break with the old commandments? If the roots of the problem of history go as deeply as we now think; if they are sunk into the mire not only of one’s being, but coil deeply into one’s metaphysical approach to life as well, then the future will not change merely as the result of killing a king, overthrowing an Ayatollah, or creating new barons of finance and entrepreneurship.

The process of history returns us again and again to the Totem configuration; again and again to the trials of ontogeny and phylogeny.

Next: Bernini: Erotic Religious Seduction Or: Back to Index