How Humans Stumbled Onto The Gods

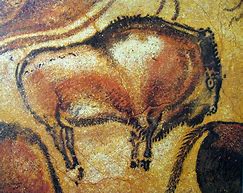

First asrising as an attempt to control animal spirits and guarantee future success in the hunt, religion germinated for many thousands of years before it makes a regressive leap into the “ethical” future. The journey begins with the cave paintings of Cro-Magnon.

Serving a purpose resembling a rain dance, such sketches of hunters and hunted game are humanity’s earliest form of sympathetic magic. This is the shamanic reenactment of a hoped for event, all in the belief that the future can be put under human control via artistic mimesis (imitation).

Crawling on his/her belly, slipping down narrow clefts that separated huge mountains of stone, fording chilly underground streams on all fours, writhing ever inward toward the dark and secret womb of the earth–sometimes a half-mile or more from the sunlit entrance–the shaman and his/her artists return to a symbolic womb in order to work their magic.

There, engulfed within a placental darkness, they labored by flickering torchlight to portray their fantastical and quite beautiful images–impregnating the future with the wish fulfillments of the oceanic newborn.

This is also the deconstructed meaning of Plato’s clever Allegory of the Cave: the secret and womb-like world is extruded into the sunlight and becomes actual; whereas the external world of real things is held up to ridicule as illusion merely, and then deposited scornfully in the darkness of the subterranean cave. Plato has pulled the cave painter’s stony, metaphysical uterus inside out, and perhaps tugged it down over our heads as well.

We have not gone much beyond this belief and behavior in our own day, and one need not look far to find modern parallels of this ancient sympathetic magic: a professional athlete making the sign of the cross before taking his turn at bat; a priestly invocation before governmental sessions to coax highness of purpose; a chaplain blessing departing fighter bombers in the Persian Gulf; a clutch of farmers dancing semi-naked, knee deep in the mucky fields of newly planted rice; college students offering up a prayer before a big exam; the blessing of a marriage; the multitudes of Christopher medals and statues of the virgin affixed to the dashboards of our cars.

Each is a reminder of the persistent human predilection for magical thinking. Each, in its own way, is an attempt to coerce the future: an attempt to compel it to live up to one’s desire–whether that desire is ethical or heinous. Each reflects “the individual narcissism that insists that somewhere there must be an omnipotence to minister to one’s wholly conscious, categorically sanctioned, sacred id need…” The environment must be compelled to become what I wish it to it be. (LaBarre, 1970).

A successful hunt, a planting, a business venture, the maintenance of a state; preparations for an immoral war–these are really concerns of the here and now. But what if one extends the future–pushes it beyond mortal existence itself?

What about heaven?

In defining and sustaining the notion of an afterlife, religion will push the controllable future far, far ahead–ultimately projecting material comfort and security into the non-visible realm. To appease the gods by right living is to appease their wrath and guarantee one of two objectives: either success here and now, or success in attaining eternal life.

Cro-Magnon begins the tradition which uses shamanic sympathetic magic to guarantee earthly success. The shaman is the lightning rod–the conductor who connects a too-stubborn reality with the omnipotence of wishes. In this sense, the shamans is the first of our gods: super-beings who can deliver very desirable goods: the future. Indeed, “it is quite plain that there were shamans before there were gods, [and that] the gods are only charismatic power-wielding shamans, hypostasized after death and grown in stature with the increased world horizons…Zeus the fire-juggler still has the many Ovidian animal metamorphoses of the ancient shamanic fertility demon…His brother Poseidon, Owner of the Sea Animals, still carries the antique trident of the old Eurasiatic shaman…The Greek nature gods are manlike for the simple reason that they were once men, mere human shamans…[And] in the Pentateuch, Moses and Aaron were still represented as snake-shamans at the court of the Pharaonic rain king, in shamanistic rivalry with his magicians” (LaBarre, 1980).

Neanderthal, earlier than Cro-Magnon, will begin a coincident tradition: ritual burials which provide archaeologists with the first evidence for the belief in souls and life beyond death.

Heaven on Earth

It will not occur to nomadic hunters to worry about nature gods–their survival is not dependent upon the weather but upon the herd; and the herd, at least between ice ages, was always there.

Perhaps an idealization of these hunter-gatherer conditions were already memorialized in the popular memory as the “good old days,” or as a plenteous Eden. As farmers, humans simultaneously became less self-sufficient and more vulnerable– an ego-debilitating trade-off for the technological advance known as agriculture. Despite the rich potentialities of surplus, farmers are vulnerable because the vagaries of weather might destroy crops or prevent seeds from germinating. Because he could not understand the forces of weather and seasonal change, the farmer had again become as dependent as a child.

And so humanity left the simple, relatively harmless animal spirits behind and found new gods–the anthropo-morphosed forces of nature themselves. Sky, earth, water and wind: in ancient Sumer, the West’s first great agricultural civilization, these were known as Anu, Enlil and Ea. Blind and impersonal, they would not at first look like their worshipers, but they were able to hear their pleas and to smell the smoke rising from their altars of sacrifice.

More often than not they listened–the priesthood would not have survived, otherwise. But occasionally they also sent devastating floods. One, coming in four thousand BCE, left eight feet of mud along the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the lifelines of Sumer’s agricultural network. Considering the vulnerability of the farmer, it is no wonder that humanity’s greatest catastrophes centered around the motif of the flood. The story of Noah is repeated in many cultures–though his wife, the old Mistress of the Animals, has been relegated to a supporting role after enjoying a brief gylanic reign herself.

The creation of the first priesthoods is tied to this same period in early agricultural history. Though the hunter-gatherer ancestors of the modern world employed enchanters and magicians, the magnified dependency of the neolithic farmer–and the specialization that agricultural surplus made possible– resulted in the creation of an entire class of beings who were freed to work full time at propitiating the gods. The great ziggurats and surrounding complexes were sites where priests and their scribes, using cuneiform writing pressed with a stylus into moist clay, kept the records of the citizen’s deposits, withdrawals and exchanges. The Escherian march had begun.

Archaic religious practices were refined to meet civilizations new needs. But as we have seen, this progress was rife with paradox: the technical advance known as agriculture brought politically and psychologically regressive elements in its train. “The emergence of an economy which involved a return to a grain-eating diet comparable to that of man’s gelada-like ancestors was accompanied by psychological and social changes which were something of a return to the original situation…Now kings could lord it over their subjects just as the primal father had done, and aspire to procure in grandeur and magnificence what they lacked of his vicious and immediate tyranny. In this way the reappearance of the primal father in polytheistic religions as the new anthropomorphic deities was the result of the coming of a new economy which recreated something like him in the agricultural communities” (Badcock, 1980). And so it is that the citizens of Sumer were officially considered slaves of the gods.

The old sympathetic magic of the ancient hunters was now rehabilitated to play a prominent role in these modern agricultural civilizations. In their deliberate rituals, the new priests promised a future in ways that not even the cave painters could have imagined.

At several places and at several times, humanity’s city and national gods will also become anthropomorphic gods–gods pictured in human form. The burning bush will give way to the beard, national headgear, and flowing robes.

The idea of a god who looks, acts and thinks like a peculiar race was a boldly successful power strategy. It was bold because it was so risky, so logically preposterous, so easily exposed by the critical faculty as a fabrication.

The risk promised an extraordinarily high rate of return. If believed, it would superbly concentrate physical and psychic controls. If a god chooses to become a person’s protector, much as if he were a parent, must not the favored one be a child of that god? Most humans were evolutionarily predisposed to be comfortable in that role, even though it officially required them to forsake growing up, as well as refuse to sample fruit from the Tree of Knowledge.

The invention of anthropomorphic deities marked a singular advance in terms of religion’s power to inspire, uplift and control. It provided ordinary mortals with a sense of connectedness to the cosmos; but everywhere that connectedness was ensnared by a pervasive other-directedness, as well as by an unspoken assertion that no individual was fit to go it alone. Instead, the individual was to be allowed the “integrity of finding his or her rightful place in the overall scheme of things” (Westphal, 1984).

The secret of the process’s paradox–uplifting at the same time that it represses–is proximity. The gods move closer to human beings both psychically and physically, thus enabling the worshiper to exert more influence in their councils. “The hominid intelligence that evolved principally to lead the individual through an increasingly complex battery of social realities sought and found actors beyond the heavens who could be influenced. The natural world and its overarching cosmos was peopled with a variety of hypertrophized human and social actors who played by many of the same rules–and who played many of the same roles–that were encountered in daily life” (Wenegrat 1990).

So the gods themselves look like mortals, eat earthly food, and speak a human tongue. The parental attachment figure of infancy becomes the adult’s god; and the cries of the infant become prayers that will elicit proximity maintenance behaviors from these attachment figures.

The consolidation known as monotheism seems logical from an ontogenetic perspective. Most humans recognize but one Father. But this consolidation also had its liabilities. To replace many gods with one is to narrow the focus too sharply. To assign the powers one being is to prepare the way for the logical paradoxes inherent in the doctrines of omnipotence and omniscience–paradoxes which will ironically threaten the existence of such gods on purely logical grounds.

The greater the god becomes, the greater distance it has to fall. Monotheistic gods are enormous targets; and such gods eventually end impaled upon the philosophical precision which had originally labored to bring them to the fore. When this occurs, the child has matured to the point where it can begin to individuate and, if need be, resist the powerful parent.

Viewed in this light, monotheism inadvertently acquired the potential to become a Trojan Horse. It successfully crushed the inquiring mind beneath the sheer weight of its enormous god; but nevertheless, it ultimately allowed the divine ramparts to be breached in as yet undreamt of ways.

Next: Akhenaten vs Henry VIII: Hellions Or Saints? Or: Back to Index