Plato’s Counter Reformation: Attack on Reality

As in the paradox of the pharaonate, the successes of both Pythagoras and Plato will ironically open the way for a final skeptical assault on the immortality project itself.

Though most evidence about Pythagoras’ life is fragmentary, we do know certain aspects of his philosophy from reports left by his students and successors. Pythagoras is a good Hindu without knowing it: his establishment of a religious order bound by strict rules as to diet and behavior, with his person as the focus; his respect for the ascetic tradition and its anti-materialist bias; and especially as evidenced by his doctrine of the transmigration of souls.

The most famous anecdote about his life has to do with his coming upon a man beating a dog with a stick. Pythagoras rushed to the man and implored him to stop, claiming that in the howl of the abused animal he heard the voice of a friend who had died some time ago.

The essence of Pythagorean philosophical doctrine is the belief in the dualism of one and many, of permanence and change– again, like the Hindu. But instead of faith in gods as proof of such a view, Pythagoras bases his mysticism on more scientific grounds–on number.

There is a permanence in this universe, and it is a permanence reflected in the unchangeability of mathematical realities. Number is a constant, and number resides at the heart of all existence.

Take the concept of triangularity, for example. Isosceles, equilateral or any other variation–all, despite the many forms they can take, participate in one concept: triangularity. Paint them blue or red, put them under the bed or deep in the closet, they nevertheless remain triangles. Destroy them all and what remains? The notion of triangularity itself. Here is something very like Hindu doctrine–though no direct linkage has been demonstrated.

The mathematical laws governing these ideal triangles do not change–hence there is something permanent in this universe. And to find one thing unchanging is to allow the seer to open the door to the possibility that not all in this universe is hurtling toward destruction as the doctrines of the materialists and some interpreters of Heracleitus would have one believe.

But the chief danger in these ideas, especially as they pass from Pythagoras over into Plato and from thence to the western world, is that these philosophers forget that these laws and ideas are human constructs, not divine ones; and the “need for metaphysics…forever strives to attain the impossible, to transcend the boundaries of the ego, to submerge itself in the All” (Fenichel, 1953).

Simply thinking about beauty or goodness independent of any particular beautiful or good thing does not guarantee the existence of such an abstract. Countless nations would go to war over ideas of truth or goodness, pretending that they were real commodities and not merely values that human beings have agreed upon ad-hoc.

It will be these essential features that will pass over into the philosophy of Plato’s Socrates, receiving its most famous elaboration in his theory of ideas.

Plato’s theory of ideas is the most influential philosophical formulation of the religious view known to human kind, and it was this development that no doubt led Emerson to remark that “philosophy is Plato; and Plato is philosophy.” “But Platonism is not a secular world view, intellectually to be taken seriously,” says LaBarre. Instead, “it is a ghost-dance religion born of troubled times” (1970).

The Platonist “counter-reformation” (Dodds) thus represents the body’s ultimate attempt to silence the internal debate once and for all, requiring the thinker to abandon her incorrect opinions so that she can submit to the truth. Here the old hunger for unity and conformity asserts itself in intellectual disguise: which stripped of its trappings stands revealed as Plato’s reaction to the “decay of the inherited fabric of beliefs which set in during the fifth century” (Dodds, 1951, pg. 207). “Within a century from the dawn of the sophistic movement Plato had reached the final phase of his thought: he was declaring that the true king should be above the laws, that heresy should be an offense punishable by death, and that not man but God was the measure of all things. With the first of these statements he announced the Hellenistic monarchies; with the second and third he announced the Middle Ages” (Dodds, 1973).

Taking a cue from Pythagoras’s ideal triangles (ibid, 390), Plato is the first western-style philosopher to formally assert that ideas themselves exist; not only exist, but are ultimately more real than matter. For modern illustrative purposes, one might argue that the idea of a car is more real than any particular, material car.

Austin Healey

Dodge Polara

Porsche

A ’59 Dodge Polara four door hardtop is most certainly not a Porsche. But they both nevertheless participate in some universal term: an idea of car. And though all cars made of steel and glass will ultimately go the way of the wrecking yard, the idea of car will endure, and will serve as an unvarying standard against which we can decide which of the many cars in this world is the best. That is, as long as humans continue think it into being.

It is important to discover this ideal because if there is no standard outside the realm of human opinion, it would be next to impossible to arrive at a definition of better or best”

This trivialization is useful because it points to a larger dilemma of utmost significance. In the realm of morals and ethics, how can one define goodness or “justice” without recourse to a standard?

In the realm of politics, how can one determine whether oligarchy or democracy is better; or in economics, whether capitalism or communism is the highest and best form of wealth distribution? And what about slavery?

When one remembers that countless lives have been lost over such and similar questions– the victims of each side dying with the conviction that their side alone possessed the truth in these matters– then the issue can be seen to have more than a mere academic importance.

A soldier would want to be sure that he was on the right side before risking life and limb, and would not want to hear sometime after such a loss that the ideals against which he fought weren’t absolutely evil after all. Without the existence of such a standard, truth becomes mere opinion, as liable to change as ones tastes in apparel or popular music. One would need to think long and hard before sacrificing oneself on the altar of such a truth.

Since Plato, much of the great matter of philosophical debate has been over the question as to whether ideas themselves exist independently of mind–the idealist position–or whether ideas are instead products of material brains and themselves dependent upon sense perception–input from the material world–for their existence.

In the Middle Ages, these two positions come to be called realism and nominalism respectively. The root word for nominalism is “name”, and this is just what Roscellinus says Plato’s so-called universals are–just names, or “flatus vocis”–which translates roughly into “word farts.” According to the nominalists, the only real things are the individual cars themselves–and it is after viewing them all that one arrives at a generic term, a sound, a word, not a real thing which describes the qualities that they all share. Thus car is an a-posteriori realization–a word that one invents after one has observed a number of them.

As one of Pinter’s interesting characters proclaims: “True? It’s more than true It’s a fact.” (Birthday Party)

But if, as the concept of a-posteriori truth implies, all universals are imaginary or human fabrication merely, then no standard for “truth” can exist except in terms of changeable, fallible human opinion.

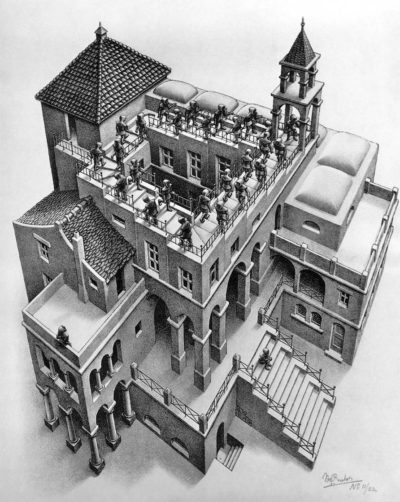

Just how influenced Plato must have been by the Vedas is made apparent in his Allegory of the Cave. Imagine, says Plato, a cave which is a kind of prison. Its inmates are chained in such a fashion that they can only look to the wall at the opposite end. Behind them roars a great fire, and between them and the fire certain attendants pass in review, bearing all the familiar objects of the material world. The light of the fire picks up the outlines of these objects and projects them as shadows upon the far wall–making it a kind of movie screen for the edification of the prisoners. As this is the only wall they can see all their lives, they assume that the shadows are real; but, as Plato points out, they are not real, but only shadows of more real (i.e. ideal) objects.

Above and beyond the cave shines the sun, and luckily or unluckily, one prisoner finds himself transported to the trap door. Emerging into the sunlight, the prisoner is stunned by the unflickering illumination–a blinding revelation. Our prisoner returns to tell the others what he has seen, but he is not believed. Obviously, they prefer their customary shadows to eccentric tales of some other source of light pure and steady.

The cave is the world, the prisoners are human kind. The shadows on the wall are material objects, and the sun is the light of unchanging, pure truth. The escaped prisoner is the Platonic philosopher or geometrician who has heroically transcended the material plane of existence and seen reality:

Euclid alone has looked on Beauty bare.

Let all who prate of Beauty hold their peace,

And lay them prone upon the earth and cease

To ponder on themselves, the while they stare

At nothing, intricately drawn nowhere

In shapes of shifting lineage; let geese

Gabble and hiss, but heroes seek release

From dusty bondage into luminous air.

O blinding hour, O holy, terrible day,

When first the shaft into his vision shone

Of light anatomized! Euclid alone

Has looked on Beauty bare. Fortunate they

Who, though once only and then but far away,

Have heard her massive sandal set on stone.

–Edna St. Vincent Millay

This philosopher is also like the Hindu sage who manages to see “beyond the veil,” who manages to see Brahman–the eternally reliable parent– behind the injurious world of coming into being and passing away. The material world is illusory, and one must transcend it. Transcend in this formulation is return: a return to the undifferentiated bliss of the cradle, breast, or womb

Plato’s theory of ideas bends all its energy toward creating a universal division. This peace shattering otherness exists virtually everywhere: in the opposition of the one and the many, the permanent and the unchanging, and in the conflict between particulars and universals. The insufficiency of the world and of life are central to this philosophical tradition.

How can one account for the the pan-cultural belief in transcendence? One modern answer is that such ideas occurred independently to dispersed human communities because of the very essence of what it is to be human. That these ideas must have been inborn–innate or a priori–and present in the human soul at birth.

There are resemblances between Plato’s a priori ideas and the later scientific view. If one translates the word soul into genes, and substitutes evolutionary behavioral imperatives for a priori ideas, one may arrive at the position that there is some hard-wiring in human beings that predisposes them to do or conceive of certain things and in certain ways (Wenegrat, Badcock, 1990). It is in this way that Karl Jung, with his theory of the archetypes of the collective unconscious, rehabilitates the spirit of Platonism in an age of science. But Platonism is both religious and mystical, whereas genetics and sociobiology are not.

But why is it that each culture arrives at a different definition of justice, goodness, beauty and so on? Interpose the Veil of Maya–the body itself. For though the soul intuitively knows the truth, it is imprisoned in a perceptually inferior body. Human consciousness receives scrambled messages from the divine–messages which have been polluted by the superficial accidents of culture, climate, experience and tradition. As Shelley has said: “Life, like a dome of many color’d glass, stains the white radiance of eternity.”

In the west, in December, one can see illustrative analogs in department store windows across the land: highly decorated, reflective metal trees. Before them, on the floor, a color wheel rotates slowly before a clear lamp. The lamp light does not change, but the color of the tree alternates through the primary colors and back again.

Now what is real? Is the tree at any one moment really blue, or green, or yellow–or is it none of these?

Herein lies the most exciting problem in the history of ideas. If the tree is equally blue, green and yellow, then it is all those colors, and no one statement about the color of the tree is any more true than any other. No observer can possess the single unvarying truth about its color, nor about anything else.

Each individual has a notion about what is good, what is just. If there is no absolute standard–no unchanging white light of truth outside of our own personal observation, then each of one’s ideas about the true and the good are relative, not absolute. There is no truth at all. No one, it turns out, is a citizen of the shining city upon the hill.

If one believes murder to be good–as did the Athenians at Melos–then it is. If one believes abortion, or prayer in schools to be good–then they are. If one believes, according to Swift’s satire, that Irish urchins would be excellent in a soup or a ragout, then they would be.

The idea that truth is relative opens the way to ethical chaos: truth does not reside in objects but rather in one’s perceptions or opinions. As Epictetus said:

“Man is not disturbed by Things, but by his Ideas about things.”

Just such a realization is made by Reverend Hale near the end of Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible. Called into Salem to find out and expose the devil, Hale at first practices with all the confidence and certainty a good demonologist can muster. “Here stands the devil,” he says, pointing to a passage in his weighty book, “stripped of all his brute disguises.” Hale believes that he shall crush Satan utterly should he show his face, but he soon discovers that the real satanic force in the town resides in the blind certainty with which the court wades into an ever deepening sea of murderous, obviously selfish accusations.

Witches are not evil supernatural creatures, not really. Instead, what is evil is the belief that witches exist, and that those unstable individuals who claim to be witches actually have the power that their delusions insist upon. The assertion, the crime, the inquiry and the punishment are all locked in a tarantula dance of mistaken metaphysics.

By the end of the play, Hale has done a turnabout. His certainty has given way to doubt, his love of scriptural truth has given way to love of life, and his faith has given way to a humble atheism that preaches forgiveness and tenderness to all earth’s frail creatures.

He tells Goodwife Procter:

“I came into this village like a bridegroom to his beloved, bearing gifts of high religion. The very crowns of holy law I brought. But where I turned the eye of my great faith, blood flowed up. And what I touched with my bright confidence, it died. Cleave to no faith when faith brings blood; it is mistaken law that leads you to sacrifice. Life, woman,life is God’s most precious gift, and no principle, however glorious, can justify the taking of it.”

The idealistic Rev. Hale has adopted the position of the Sophists, and it was against them that Plato took up his philosophic standard.

Protagoras, one of their chief spokesmen made the famous remark: “man is the measure of all things; both what they are, that they are; and what they are not, that they are not.” “Truth telling operates well only to the extent that everyone involved understands its fragility; it is human, it is fallible, and it is political to the core. It is predicated on convention and social agreement” (Raskin & Bernstein 1987).

This is the legacy that students are beginning to receive from linguistic analysis. The relation between signifier and signified is blurred, and the tendency to reify nouns now stands exposed for what it is. “Functionally speaking, `God’ is really a pronoun, a pronoun whose referents, connotations and denotations differ with every person and every society using it…Theology is therefore phatic vocalization in the human primate, not referential speech…The locus of the subject matter, obviously, is somehow in societies and in men’s minds, not in the outside physical universe” (LaBarre, 1970).

The Bible is not the word of god; rather it is merely a work of days and hands.

“Reality is as we desire it to be. Our cultural disquisitions about reality are as autobiographical as are our theological maunderings about God” (Stein, 1983).

Thrasymachus, one of Protagoras’ disciples, expresses a similar skepticism about the value of reifying the good or justice in Plato’s Republic. Exasperated with Socrates’ prying attempt to find the truth about what constitutes a good or a just government, Thrasymachus explodes: “Might makes right; ever it has been thus, and ever will it continue to be.”

Without absolute truth what must life become?

Thucydides’ account of the Athenian treatment of the Melians was thought to be an excellent example.

The citizens of the island of Melos wished to remain neutral in the sad spectacle of the Peloponnesian war. The Athenians arrived with armed forces and threaten to coerce alliance in their cause. As reported by Thucydides:

“Athenians: For ourselves, we shall not trouble you with specious pretenses (explaining our planned invasion of your island should you refuse alliance)– either of how we have a right to our empire because we overthrew the Mede, or are now attacking you because of wrong that you have done us– and make a long speech which would not be believed; and in return we hope that you, instead of thinking to influence us by saying that you did not join the Lacedaemonians, although their colonists, or that you have done us no wrong, will aim at what is feasible, holding in view the real sentiments of us both; since you know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

“Melians: As we think, at any rate, it is expedient– we speak as we are obliged, since you enjoin us to let right alone and talk only of interest– that you should not destroy (us)…And how, pray, could it turn out as good for us to serve as for you to rule?”

“Athenians: Because you would have the advantage of submitting before suffering the worst, and we should gain by not destroying you.”

“Melians:…You may be sure that we are as well aware as you of the difficulty of contending against your power and fortune …but we trust that the gods may grant us fortune as good as yours, since we are just men fighting against unjust…”

“Athenians: When you speak of the favour of the gods, we may as fairly hope for that as yourselves; neither our pretensions nor our conduct being in anyway contrary to what men believe of the gods, or practice among themselves. Of the gods we believe, and of men we know, that by a necessary law of their nature they rule wherever they can. And it is not as if we were the first to make this law, or to act upon it when made: we found it existing before us, and shall leave it to exist for ever after us; all we do is to make use of it, knowing that you and everybody else, having the same power as we have, would do the same as we do….”

The Athenians are simply following the law of life as described by a Thrasymachus or a Callicles. Ever thus has it been in operation, and ever so shall it continue. Success is the final arbiter of goodness, and the weak would exercise the force required if only they could.

But such behavior is not a necessary consequence of atheism or of the relativity of truth. The sophists did not argue that humanity could not invent good moral standards by which to live. Indeed, man-made truths might be preferable to those communicated by priests.

Fear of the gods has not made humans good. Instead fear of the state and its punishments, or the equally powerful fear of disapprobation, has. The gods would not have their children behave less murderously, but rather would have them raise armies so as to murder others (non-kin) in their name. This explains the presence of the chaplain on the aircraft carrier deck we alluded to earlier.

Still, the scapegoat argument persists — believed no less by Ben Franklin as revealed in his letter to Thomas Paine. He argues that belief in the gods is necessary to the maintenance of virtue. What is really meant goes unsaid: belief in the gods is necessary to the maintenance of the state’s definition of virtue–a definition which just happens to be coincident with the pronouncement of that same state’s gods.

The value integrative belief and behavior aligned with the gods must not be questioned, else human life goes to pieces:

Tara! Tara!

To battle, to battle–haste, haste–

To battle, to battle, aha, aha!

On, on, to the conqueror’s feast

From east and west, and south and north,

Ye men of valor and of worth,

Ye mighty men of arms, come forth,

And work your will, for that is just;

And in your impulse put your trust,

Beneath your feet the fools are dust.

Alas, alas O grief and wrong

The good are weak, the wicked strong;

And Oh, my God, how long, how long;

Dong, there is no God, dong;

There is no God, dong, dong.

Clough, in his Victorian nightmare, hears the bells tolling the terrible message that his god is dead, dethroned by new science. If god is dead, fears Clough, then there will be no force higher than human beings to arbitrate, to instruct, to enforce a moral order. The victors of wars will write the textbooks, and present their case as unfailingly just.

But the narrator in Clough’s poem has misread history–an especially ironic slip for a citizen of what was rapidly becoming the world’s largest empire–through brute force. As the Athenians knew, it has always been this way, and the respective gods of both sides continue to bless their troops prior to each sacred battle.

John Donne, a metaphysical poet of the seventeenth century, expressed a similar dismay, this time not with reference to the work of Darwin, who was yet to be born, but at the discoveries of Copernicus and Galileo:

And new philosophy calls all in doubt;

The element of fire is quite put out;

The sun is lost, and the earth;

And no man’s wit can well direct him

Where to look for it;

‘Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone!

Translate: there is no Father in the stars. The Father is dead; probably the Mother also. This is the separation anxiety borne of a profound object-loss, and the poet feels himself ill equipped to begin to make his own world.

Plato, of course, was striving for certainties amidst the breakup of the Athenian world, brought on in part by the Peloponnesian war and its aftermath.

“Plato understood well the connections among tragedy, democracy, Oedipal revolt, and ambiguity. Plato’s political solution was to propose a system wherein we might be assured of having virtuous, not tyrannical, fathers of the city so that we could all be good children again and there would never be any need for rebellion or even a peaceful challenge to authority” (E. Sagan, 1979).

After all, who, along with T.S. Eliot, does not yearn for certainty, for the assurance that the attachment figures shall maintain their proximity, for the pacifying true knowledge on which to base one’s life?

And indeed there will be time

For the yellow smoke that slides along the street,

Rubbing its back upon the window panes;

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

There will be time to murder and create,

And time for all the works and days of hands

That lift and drop a question on your plate;

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.

In the room the women come and go,

Talking of Michelangelo.

We live, according to Eliot, in a world where all one’s visions will ultimately need revision–a place where today’s truth becomes tomorrow’s falsehood.

A man saw a ball of gold in the sky;

He climbed for it, he achieved it;

It was clay.(Stephen Crane)

Have we misjudged the value of clay all along?

Next: Tragedy Unmasked: Meet the Trojan Horse Or: Back to Index