Ecce Homo: Nightmare In Eden

Surveying the savage disintegration of their temporary island paradise, Piggy asks Ralph: “What makes things break up like they do?”

Identifying the source of Evil has dominated religious discussion for centuries. And for those same centuries our best thinkers have attempted to find an answer while using the same faulty equipment.

Evacuated from a world at war, a group of English boarding school youths find themselves abandoned on an Edenic tropical island. The crash that brought their plane down has killed the crew members–the only adults accompanying them on the journey to escape.

At first the boys celebrate their freedom from adult restraints, and for a brief moment are presented with an opportunity to create a paradise that previous adult generations have never been able to achieve. Their early enthusiasm soon gives way to increasingly sinister bickering between two natural leaders, as well as to the discovery that not only are they alone on the island, but also that the possibility of rescue is remote.

By now, the fast fading recollection of the orderly parental home represents “heaven” to some, and its siren memory divides the boys into two rival sects. One is the Dionysiac group of hunters, who ignore rescue and focuses instead upon the ritual of the hunt. On the other side: the reasonable “fire-tenders” who resist time wasting attractions in order to alert the parental world of their need for rescue.

One uncomfortable fact looms in the background: Since the adults–the only gods in this novel–have wrecked the world, it is pointless to appeal to them for salvation. London has been destroyed. The entire adult world is itself in need of rescue. So it is that the conflicts on the island are a microcosm of the larger conflicts that have always smashed up human endeavor.

The adult world to which Ralph would have the boys return–despite its “reasonable” facade–has a long history of war and conquest behind it. Its lethality and venality are largely invisible to its own citizens. But they are visible to those peoples whom they dominate.

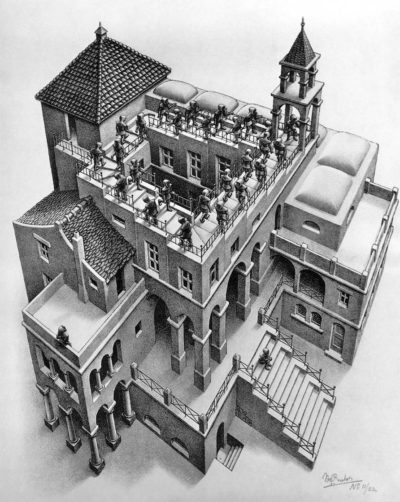

As has always been the case: empires mask their greed and lethality behind a polished institutional facade. The rule of law, justice based orders, preservation of democracy–terms like the these are clear harbingers of tyranny.

We must remember. Violence is not banished by “civilized” adult culture. It is re-defined, sacramentalized, and then brought under a useful political control. Civilization outlaws acts of individual violence within its precincts. But it does not demand an end to the use of lethal force against others. Instead it monopolizes violence, investing its exercise in its agents: the police and the armies.

When the boys turn on each other at last, they do not become savages. They merely express those once useful, pugnacious behaviors that brought is here. They are, what we are. No wonder the boys on Golding’s island continued with the old habits and traditions. They claim to locate the source of “evil” in the body of the dead parachutist whom they name “the Beast.” This was the only answer that made sense; it was the only answer that enabled them to face the problem of existence without suffering existential collapse. It enabled them to objectify, externalize, blame the Other, and thus begin to control their doubts and fears.

But it was the wrong answer–the wrong metaphysic. Simon knows the truth, and imagines that he has heard it from the pig’s head on a stick . A sow is sacrificially, cruelly slaughtered as sport by the boys and offered as an appeasement for the beast. Its severed, dripping head rests impaled on a spear in the forest clearing, transforming what was thought to be a paradise into an oppressive, terror-filled hell of one’s own making:

Simon stayed where he was, a small brown image, concealed by the leaves. Even if he shut his eyes the sow’s head still remained like an after-image. The half-shut eyes were dim with the infinite cynicism of adult life… Simon looked up, feeling the weight of his wet hair, and gazed at the sky. Up there, for once,were clouds, great bulging towers that sprouted away over the island, grey and cream and copper colored. The clouds were sitting on the land; they squeezed, produced moment by moment this close, tormenting heat. Even the butterflies deserted the open space where the obscene thing grinned and dripped. Simon lowered his head, carefully keeping his eyes shut, then sheltered them with his hand. There were no shadows under the trees but everywhere a pearly stillness so that what was real seemed illusive and without definition. The pile of guts was a black blob of flies that buzzed like a saw. After a while these flies found Simon. Gorged, they alighted by his runnels of sweat and drank. They tickled under his nostrils and played leap frog on his thighs. They were black, and iridescent green without number; and in front of Simon, the Lord of the Flies hung on his stick and grinned. At last Simon gave up and looked back; saw the white teeth and dim eyes, the blood– and his gaze was held by that ancient, inescapable recognition…“Fancy thinking the Beast was something you could hunt and kill!” said the head. For a moment or two the forest and all the other dimly appreciated places echoed with the parody of laughter. “You knew, didn’t you? I’m part of you? Close, close, close! I’m the reason why it’s no go? I’m the reason why things are what they are?”

In the old days, our behavioral sins were attributed to demons. To locate Satan and his minions outside the self was a stroke of genius for the theologians. For though Satan was cast as a formidable enemy, there were charms that could be employed to prevent his breaching the fortress of the soul. These charms the priest had in his sole possession, and in advanced cases of demonic invasion, he could use them to drive incubi and succubi from the interior of the body itself.

But to discover that this Satan is within the self as a part of our evolutionary heritage–that is another matter altogether.

This is exactly what the pig’s head tells Simon: Wherever you go, I am there. Man and Beast are inseparable because they are aspects of the same being.

Golding’s novel ends with a Deus ex Machina: a blonde god descended from the skies to solve the problem. In this case, it’s the arrival of a cannon-bristling British cruiser. The boys have already begun their final battle, and are on the beach moving toward the kill. They are stunned, perhaps like the Incas or Mayans. A gleaming white war machine lies anchored just off shore. Standing on the beach before them, a mythic savior: a Royal Navy commander dressed in white.

The irony is palpable. We are now back where we started. Nothing significant has changed. Golding has taken us to the edge of despair, to the edge of a very dark truth. He shows us the reality of the past, but also a quite certain, quite reasonable movie of the future.

A future that is now inescapable: an unraveling climate, a world population approaching 10 billion, accelerating soil and aquifer exhaustion, the dangerous St. Vitus dance of a collapsing American Empire…all dwarfed by and an enormous Exodus of peoples fleeing areas that can no longer sustain them. No border will be able to withstand their their assault.

Are we ready for this? Is our thinking clear?

Long ago an evolving humanity reached the outside of a cultural and biological envelope that has ever since prevented it from breaking with the past. The drop-down menus for the future have been enclosed and limited by that same envelope. These choices represent the limits of the possible. Thave kept the human journey upon this planet well within certain intolerable tolerances.

Why didn’t the human neocortex–the sapiens part of the genus homo–do a better job when it fashioned culture and engineered its future history?

Certainly it had the neural horsepower to design a program for the future that would be both reasonable and secure–didn’t it?

Or did it?

Poised at the evolutionary cusp that peaked at the ragged edge of neural evolution, the new brain faltered as it stared with untested, but fabulous powers, into an uncertain future.

There was so much to do; and so much of it had never been tried before!

Lacking experience, and shy about asserting its new powers, the new brain deferred to the ancient reptilian menu as it lisped the phrases that would become the script for the future.

And so we act out the dramas of our lives in an ever changing, ever familiar world. Adorning our fragile limbs with a gold that is not of earth but which comes from the cores of long extinct, collapsed stars, we motor down glacial till expressways to keep an ancient appointment with the future. Our engines fueled by the rotted carcasses and flora of a carboniferous past, we are lured toward an illusory tomorrow by those recent evolutionary inventions, the sirens of the reasoning neocortex.

But not even they can enable us to achieve enough velocity to escape the enormous pull or our ancestral heritage: the ancient, reptilian and stone age forebears who brought us here, and who clasp us to themselves through our ritual, our need for hierarchy, our easy susceptibility to indoctrination, and our love of myth.

Next: Why Revolutions Fail And History Must Repeat or back to Index