Akhenaten or Henry VIII?

Hellions or Saints?

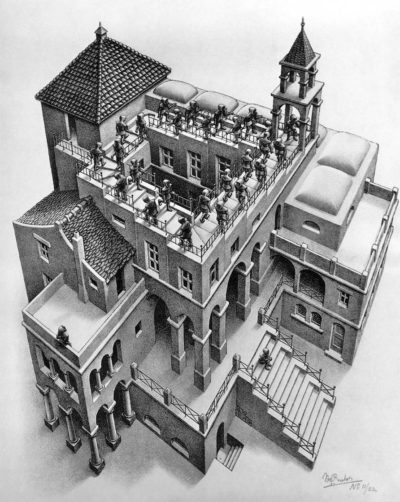

Much like Northwest natives who believed that earth was the the spiritual repository of departed ancestors, we moderns also tread upon the ancients who have preceded us. The patterns and beliefs of the past are never really surpassed, and new generations merely reiterate the ancient themes and compulsions. The Hypostyle Hall of Karnak, the minaret, the cathedral, the pulpit or the temple: these architectures are the stony flowers of those faiths that spring from the ancient turf of human vulnerability, reminding us that the secret of all renewal is merely return.

But sometimes, even from the crypted heart of the stony past, one can hear a different message: a defiant whisper winking upward through the spiraling centuries. This whisper informs us that our last ally within the bony prison of the skull has been planning its escape with care. For good or ill, its unfinished work promises that sometime, somewhere, someday, the proponents of surrender and orthodoxy, like the administrator of Kafka’s Penal Colony, shall eventually fall into the grim machinery of their own metaphysical constructions.

In Mesopotamia, the people are pinned to the mat almost before the match begins. The Sumerians will be among the first civilizations to employ priests and priest-kings to organize ceremonies designed to direct the energy of the natural forces of the sky, wind, water and earth. Their powers will grow enormous, and by the fourth millennia BCE they will become the absolute rulers of the state.

Mesopotamia’s stepped ziggurat fuses in the mind’s eye with Egypt’s limestone cased pyramid: It will be the fate of the Egyptians to labor under the weight of their peculiar theocratic tradition, never able to break with the rule of priests and god kings for the entire length of their history. But chained as they will be to this theocratic wheel of Ixion for over thirty centuries, the pharaohs that people venerate will nevertheless pave the way for the destruction of the form itself.

The powers claimed by the Pharaoh require him to be as remote and awesome as a true god ought to be: a dweller like Zeus on Olympus, or secluded in his Great House. Like Oz, they must maintain enough distance to retain a god-like authority, especially for those who never contact the pharaoh, never see his person, and only hear of his actions through second hand.

But to maintain this distance is also to invite political insecurity. It is to begin to gradually lose touch with the government either through the machinations of deceitful advisors, or by the venality of scheming priests who control the public ceremonies and the treasuries that the other gods of the state require. For though the Pharaoh is an Osiris replica with his own priests and cult rituals, his relative isolation makes him something of an absentee. There are still many other gods, and they and their priests will continue to vie with him for public prominence and power.

The worm lurking at the core of pharaonism is both latent and dangerous: what mere mortal can convincingly bear up beneath such an outrageous metaphysical expectation? What Father of the People can perpetually carry the burden of omnipotence that human infantilism invests him with? What ancient Mount Rushmore can be sculpted to solidify the deception, the illusion?

Weaker pharaohs–either out of touch with political forces or, what’s worse, no longer able to maintain the fiction of divinity to those who matter–will be challenged not only by their nomarchs and viziers, but also by the priests of Amon-Re. Thus, as Egyptian power declines through a long drawn out series of foreign and domestic reversals, so does the unchallenged divinity of the pharaoh.

Consider these two Old Kingdom pharaohs as revealed in their portraiture–magnificent artistic renderings that precede the soon to come decline of the god king. Each possesses the poise, grandeur and power that a clumsy Ramses will much later emulate, revive and hope to achieve.

Here is Khafre of the Old Kingdom, Horus perched on his shoulder, enveloping the pharaoh’s sacred headdress with his wings. In Khafre’s time Egypt was relatively unchallenged by external foes, and the power and majesty of the pharaoh was absolute.

Or consider his brother Mycerinus and his wife: beautifully composed, balanced like two missiles on a launch pad, ready to lift off into eternity.

The imperturbability and confidence exuded by these supremely well finished sculptures speaks volumes.

Sometime around 2100 BC and for the next century or so, Egypt’s Old Kingdom will be plunged into the chaos of agricultural disaster followed by an aristocratic rebellion against the totem-king himself. During this time–and less than five hundred years after he was laid to rest–the great pyramid of Cheops (father of both Khafre and Mycerinus) will be ransacked and robbed of its riches and royal corpse.

By perhaps 2000 a new era–the Middle Kingdom–will be inaugurated, its pharaohs coming from the ranks of the successful nomarchs and their offspring. But while they maintain the fiction of god-head, they are unable to play the role as convincingly as did pharaohs of old. As their portraits suggest, they can no longer rule from behind the impassive, unearthly mask of Old Kingdom style divinity. Instead they must be portrayed as tough, human rulers who will use the power of the state to enforce their will.

The worst is to come. Sometime around 1750 BCE a semitic tribe called the Hyksos will invade from the northeast. Possessing both chariots and horses– neither of which the Egyptians have ever before seen–these invaders will easily conquer and rule for perhaps a century. Finally, Egyptian nobles–yet another reprise of the theme of the band of brothers– will gather together armies, learn to use the chariot and the horse, and ultimately drive the Hyksos from the sacred land. Under the Thutmosides, the “fighting pharaohs,” Egypt will come to extend its “sway over Asia, Nubia and the Sudan, [recovering] much of the prestige and authority of the crown” (Aldred, pg.27).

Once again, the Father in the Great House seems to be reestablished and secure; a fact which makes the appearance of Amenhotep IV, the heretic king, all the more militarily and politically inexplicable. This pharaoh, son of the powerful Amenophis III, will prove to be one of the most puzzling heroes in human history.

The Monotheist Gambit

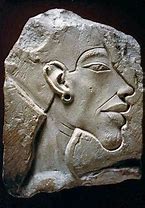

Look at the image of Amenhotep and his wife Nefertiti. Unsuited for the brutal subtleties of power politics, Amenhotep seems to resemble a gentle Prometheus bent upon dramatic overturning of convention and the old order. As pharaoh in an already ancient polytheistic culture, he finds himself surrounded and hamstrung by the powerfully entrenched priests of the god Amon. Not that he–or any other pharaoh–would have been absolutely free in this regard. This encroachment began long before his reign, but now, everywhere, their serpentine grasp encumbers this pharaonic Laocoon. Now it is impossible to move with a spontaneity that is unfettered by precedent, ritual and priestly prerogative–a fate that all presidents and queens must to some extent share, but with a few notable exceptions.

It is from within this context: as the son of one of the most successful pharaohs in history, as the heir of both an empire and the armies necessary to sustain it, and as the living, totemic center of a plethora of tradition-sanctified polytheistic cults–that Amenhotep hits upon an incredible and otherwise spectacularly unnecessary idea: there is only one god.

The divine reality which Amenhotep envisions is singular (monotheistic), not multiple (polytheistic). Bodied forth as a symbol, the god assumes the form of the solar disk of Aten–a name for one of Egypt’s earliest sun gods. Overhead, visible and accessible to all–though the pharaoh is more intimate with it than others– the god can be accessed by anyone and everyone anywhere in the world.

Bek’s marvelous Amarna portraiture presents the pharaoh as a somewhat bizarre, gentle, homely domestic figure: a family man dandling his daughter on his knees, even to the point of being portrayed kissing his wife Nefertiti in public. In each the Aten sends its rays down to earth, its powerful rays ending in a caressing hand that soothes and comforts those below.

In this portraiture, the Aten is not tucked away in a shrouded tabernacle deep within the heart of a forbidden temple. Neither is it guarded by jealous priests, nor successfully approached only by mastering the intricate details of ritual. Instead, the Aten is found shining in the field, glinting off the waves of the river Nile, burning its way through the unbridgeable gulf between life and death at sunset and at dawn. The Aten offers a universal son-ship to downtrodden humanity that levels, uplifts and shatters the old hierarchies and dependencies.

It is impossible to know absolutely whether his religious revolution was genuinely spiritual, or whether like Henry VIII, his antagonism to the Priests was founded upon dynastic or financial imperatives. Nevertheless, Amenotep (Akhenaten) was an originator–the creator of a revolutionary new religion that canceled the Egyptian pantheon. Henry VII, however, remained a Catholic to the end of his life. His main goal, his main achievement, was to replacing the Pope as titular head, as well as to re-directing tithes and bequests to the Crown, rather than to the Vatican treasury. Henry was not a devout religious reformer, and most key elements of Catholic ritual and belief continued under this first iteration of the Church of England.

When the Amarna images are matched against the well documented venality of the Tudors, we are given good reason to conclude that Henry was vastly more worldly, venal than Akhenaten. That he was clearly motivated by dynastic goals, as well as by seizing the wealth with the church. He sought not to transform Catholicism, but rather to reboot it with himself, rather than the Pope, as the head. The necessity of receiving Papal permission to divorce was certainly the initial catalyst for this wide ranging coup.

The psychological testimony provided by the differences between Amenhotep’s and Henry VIII’s portraiture is persuasive:

Exotic, unassuming Amenhotep:

And a pugnacious Henry:

The image of Henry projects power and bloated confidence, as well as a palpable threat of violence as evidenced by the hand placed upon a dagger and a short sword hanging readily from his belt. Styled “Tte Defender of the Faith” until his break with Rome, Henry is a man of the world, a lover of good feasts, a tough and ruthless character who will get what he craves by any means necessary.

And while the images, motives and personalities are enormously different, haunting parallels exist between these kingly and pharaonic trajectories:

Each was an Oedipal destroyer of the Father: Amenhotep dethroned the traditional deities and their priests; Henry displaced the Pope, expelled the Catholic clergy from England, and confiscated innumerable properties the Holy See had accumulated over the centuries.

With a final twist of both royal knives, Henry ordered the exhumation and burning of Thomas Becket’s corpse, a hero of British Catholicism, as well as a significant destination of pilgrimage. Akhenaten ordered the erasure (with chisels) of all Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions that mentioned names of deities of the old polytheistic pantheon.

Yet, despite these amazing parallels, only one of the two could ever be mistaken for a saint or an idealistic liberator.

So it seems that Amenhotep, like Paul, was truly struck by a vision on his own personal road to Damascus.

Akhenaten was described as a criminal by those he displaced, and it’s not surprising that his re-programming of the ancient totem loop produced this level of hostility. The Father of the polytheistic formula would have ceased to exert his unquestioned control from beyond the grave, and the ka of the deceased kings would no longer factor into the Egyptian political equation. The red-hot stone of the sun would be rolled atop the ancestral graves that contained the dead chieftains, and the repressed would not thereafter be allowed to return. In this way, the Totem as ancestor vanishes, and is replaced by an immediate, more humanistic reality–the Aten–which is here and now.

If this view holds, then one may imagine that Amenhotep was to conventional religion and its old metaphysic what the Marxists were to capitalist economics and politics–at least in theory. And like the “father-slaying” Marxists at the turn of the century, Amenhotep meant business.

This first universal monotheism in the history of the world comes centuries before the Hebrew monotheistic prophets Amos and Isaiah. But where Amos and Isaiah were uncomplicated, atavistic apostles of the self-willed, world-drowning Yahweh, Akhenaten’s monotheism strikes a significant blow at the Totem apparatus itself; a blow whose delayed reaction threatens to bring it to its knees.

His revolution against the old order inaugurates what Diderot perhaps would have recognized as an emancipating precedent on the road to becoming independent and self-caused. Diderot is reported to have said:

“Man will not be free until the last King is strangled

with the entrails of the last priest…”

Certainly, the hymns that Akehaten himself composed in praise of Aten would have pleased that other rebellious son of the Enlightenment, Thomas Paine, who sought evidence for god in the text of nature alone.

Values like these would place Akhenaten very near the top of a revolutionary hall of fame–albeit with mixed motives perhaps–the actors and actions of which were destined to repeat themselves over and over again in the coming centuries:

“It is certain that the drama in the primeval horde was not a singular event, but took centuries and was repeated innumerable times…[today] removal of kings by organized violence…comes closest to the parricide in the primeval hordes…Since…1793, we have seen the murder of the Czar, the Serbian king, and of other monarchs…there will certainly be others…the historical development we can observe is only a small part of an evolution that took place during many thousands of years…” (T. Reik, 1957).

Or as Cassius, dipping his hands into the pooling blood of dying Caesar, who prophesies:

How many ages hence

Shall this our lofty scene be acted over

In states unborn and accents yet unknown!

But the Atenist revolution slew more than authority figures. It attacked the entire nexus of creaturely guilt, dependency and fear. What else is one to say of the fact that “the adherents of Aten rejected completely the Osirian conception of life after death–the journey of the wandering soul to the West, the Last Judgment before Isis in the Hall of the Two Truths. It even rejected the quite attractive image of the afterlife–“the blessed in the Elysian Fields where the corn grew to a height of nine cubits in a sort of eternal springtime.” (Aldred 1968)

Akhenaten tilts magnificently at millennia of accumulated, comforting delusion. As with the much later Gracchi, his failure is immediately assured, and almost as immediately spectacular. One can imagine that outside his court the country remains sullen and unswayed. Who would willingly exchange sacred tradition–and the security of the old Totems– for this novelty? Who can give vent to an aggression against the primal father that thousands of years of organized life have effectively repressed or sublimated? And what about the cadres of now displaced employees associated with the temple complexes throughout Egypt?

Still worse from a geopolitical point of view: while Akhenaten composes quite beautiful prayers and supervises the decoration of his new capital, Akhetaten, his generals at the empire’s frontier plead for reinforcements against new barbarian incursions. But the government of this visionary leader is either indifferent to the maintenance of empire or in disarray, and so no help comes.

None of his reforms endure beyond his seventeen year reign–a reign that ends shrouded in mystery. But “the death of Akhenaten must have been generally regarded as an especially dangerous moment in the fortunes of Egypt. Abroad it had just suffered losses in North Syria…in Palestine unrest threatened the Egyptian position in the key center of Gezer…at home, the age-old shrines lay abandoned; and while doubtless the common people still clung to their household gods, all organized religious activity was in confusion…In the world of the Late Bronze Age this would have been a most serious cause of anarchy and a crisis of confidence” (Aldred, 1968)

In the words of his successor Tutankhamen’s restoration stela:

“Now, when His Majesty appeared as King, the temples from one end of the land to the other had fallen into ruin; their shrines were desolate and had become wildernesses overgrown with weeds; their sanctuaries were as though they had never been; their precincts were trodden paths. The land was in confusion for the gods had forsaken this land. If (an army) was sent to Asia to widen the frontiers of Egypt, it met with no success. If one prayed to a god to ask things of him, he did not come.”

At Akhenaten’s death the powerful priests of Amon reasserted their control. The capital was returned to Thebes, and the names of the displaced gods were restored to the recently edited monuments.

But these new successors–the rebellious sons–clearly understood the significance of what had been attempted. And the magnitude of the threat merited a commensurate response. They “were determined to efface all his memorials and those of [Akhenaten’s] immediate successors. The official building at Akhet-Aten [sic] were desecrated and later demolished, and its stones used for the foundations of temples that Ramesses II built on the opposite bank at Hermopolis. The name and figure of Akhenaten were hammered out wherever they appeared…the king lists were amended to exclude the successors of Amenophis III up to Haremhab, and…if any unavoidable reference had to be made to the former reign of Akhenaten, he was referred to under a circumlocution as `that criminal of Akhet Aten’…Lastly, the tombs of the `heretic’ kings were sought out and their burials desecrated” (Aldred, 1968).

Perhaps he was a visionary; perhaps he was a charlatan. Perhaps he suffered a mental deformation related to the dolichocephalic skull; perhaps his appearance was symptomatic of marfan’s syndrome; perhaps he was a paranoiac whose “personal delusional system…became public property and was invested with the dignity of a state religion” (Badcock, 1980). Whatever his intention, Akhenaten’s rebellious response to his place and times forges a potential tyrant-slaying model for the critical intelligence.

I am reminded of the uproar made when Lyndon Johnson lifted his shirt on national television to reveal the scar left from a gall bladder operation. Lese majeste’ is a crime not because it reflects upon the ruler, but because it reflects upon the people who have invested their lives and future prospects in that ruler. The fallibility of the “Father” disturbs their trust, their sense of well being. For people to glimpse of the frailty of their leader is to release a quantity of cynicism into the psycho-political atmosphere; and the problem with cynicism is that can manifest itself both as apathy, or as a stiffened resistance to the extra-mortal mana of presidential successors.

One way to test this assertion is to ask whether Washington’s, Jefferson’s or Lincoln’s monuments would be built in the same style–with all the trappings of classical divinity–today. And even if they would be, might there not be memic currents set loose in the world that would begin to wean more and more of our fellow citizens away from such devotions? Presidential images on coins? Carved into mountain tops? Are you kidding?

Next: Post Modern Oedipus Or: Back to Index